Imagine the number of painstakingly reported pieces on the growing economic divide in the U.S. that you’ve seen, and likely read, in the last few years. We, journalists, are so well-intentioned with our statistics and our scorn.

We’re doing our duty—at least numerically. But are we doing our duty emotionally? Are we giving the privileged public a felt sense of what the experience of poverty is actually like?

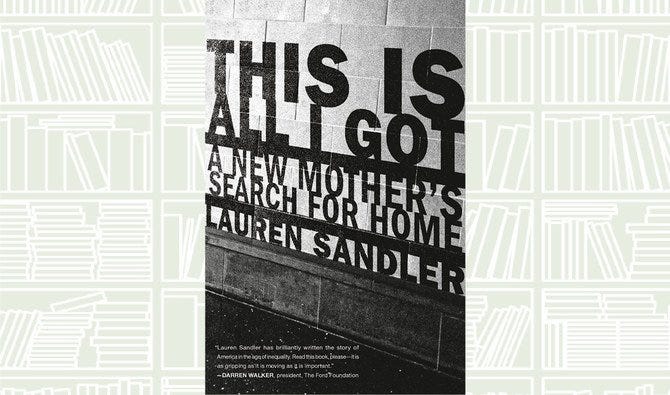

Reading Lauren Sandler’s new book, This is All I Got: A New Mother’s Search for Home, made me realize that the answer is an emphatic no. Her book is a visceral, compassionate act of accompaniment—a white, middle class writer walking alongside a Dominican, first-generation student and mother whose address happens to be a homeless shelter. She waits with her—in all those profoundly dysfunctional government offices, she waits. She rides the train with her—from the Bronx to deep Brooklyn and back again. And she listens to her. She listens to her for 12 months straight and this book is the altar to that listening.

If you’ve read Random Family, this is its equivalent—a work of such journalistic precision and humanistic tenderness that you will not want to put it down. You will be heartbroken, but you will also be changed. You can forget the statistics, but you won’t forget Camila’s journey—or the systemic cruelty that shaped it. After turning the last page, I couldn’t wait to ask Sandler these questions…

Courtney: I find your relationship with Camila to be so compelling. You all genuinely like one another. You come to really trust one another, it seems. Was there ever a moment when she asked you -- “so what's your take on all this?” Did you show her the book before you submitted it to your publisher and what kind of veto power, if any, did you give her?

Camila didn’t ask my take on the failures of the social service system – but I was so open about my outrage that she didn’t have to! In terms of my take on her, that’s a bit more complicated. I offered – and then insisted – on going through the manuscript page by page with her, but she didn’t want to. It was really important to me that she be a part of fact-checking and also be prepared for how I present her. But she had a real block about doing that.

In fact, only now is she listening to the audiobook; she wanted to experience it that way instead of on the page. I was always clear that this was a book I was writing, with her experience at the center, but that it wasn’t something we were writing together, even if in so many ways, it was a project we shared. If she’d balked at anything in the draft, I would have certainly discussed how to make the book what I felt I needed to say, in a way that allowed her to feel seen and respected. But I never had that chance, which certainly kept me up at night.

Suffice it to say that we are very close, on a daily basis, even as she’s encountering this story of her year, through my perspective.

The amount of time that Camila spends in government offices waiting on dehumanizing and dysfunctional service is appalling (wait times seem to be, on average, at least three hours). I think it's something we all think we know about experiencing poverty, but don't actually have a visceral, enraging sense of it if we haven't experienced it or read a book like yours. What was your biggest surprise about being along for all that waiting?

I’m so glad you asked about this. The deadening, maddening, crushing experience of shouldering what scholars Pamela Herd and Donald Moynihan have termed “administrative burden” is truly what I was not prepared for. The waiting. The impossible paperwork. The constant closure of cases for no clear reason. Being sent from office to office all around the city, to wait for hours and hours at a time, without even being able to pee, missing work and school, being treated like a pariah – it is brutalizing.

I watched, over the course of a year, Camila transform from a confident, ambitious young woman – the brightest light in any room – into a shadow of herself. I watched her face change, her walk change, her view of herself and her prospects change, all through this process. It’s horrid enough to witness the lost wages and missed exams, but I watched her spirit extinguish as well. All at the hands of a system that ostensibly exists to help, not hurt.

As much as it is about a mother’s first year of life, there isn't a whole lot of material here about Camila's experience of becoming a mother. I’m thinking of the existential dread and exhaustion and anxiety that seems to typify the transition for so many of my peers. Is that because she didn't experience motherhood in that way with so much else to worry about, or did you not have room for it?

Honestly, she didn’t have room for it. There was no time, no psychic space for it. The crisis of new motherhood was always shadowed by the myriad emergencies of poverty. There’s a scene in the book in which she goes to a La Leche nursing circle at a yoga studio, and the woman leading the circle instructs her to savor the luxury of her first trimester with her baby. After the class ends, she gets on the subway to go straight to a government office in a housing project. I did see other women in the shelter crushed by depression after they had their babies. I watched them retreat, go dark. But Camila felt she couldn’t afford to waste a minute in finding housing, applying to schools, chasing down child support, and more. And honestly, I think that she feared that if she stopped to feel what so many of us do in our transitions to motherhood, she would be pulled into quicksand.

This is a micro story that leads one to ask a million macro questions. Chief among mine is how can we recast housing as a human right and learn from countries that are doing it better. Did your research on Camila’s experience lead you to any models in other countries, or in certain cities or counties in the U.S., that gave you hope it could be done better?

Honestly, we can look to most countries -- especially European ones, most especially northern European ones of course – for alternatives. Those alternatives don’t just focus on housing, they focus on the entire constellation of factors that make for a most just, equitable society. A living wage. Reasonable public assistance. Child care. Health care. We tend to isolate these factors, silo them. That doesn’t address how people actually live, what constellations can pull them from the precariate into poverty, as we’ve been seeing for years here, and are now seeing at formerly unimaginable numbers, at warp speed.

But as I write nothing can happen in any life without stable housing. It’s the foundation of everything. And its absence is nothing short of a human rights crisis, I agree. In the US, there are some programs that serve as good pilots to address this. Worcester, Massachusetts – where my mother grew up, in fact, and where her family class-jumped from immigrant poverty in a very different time – ended homelessness for a spell with a combination of cheap structures and intensive social support. But that program faltered a bit, and so did the people in it – constancy is key.

Honestly, the program we need is massive economic restructuring to start, and widely available housing vouchers, and new housing with, in many cases, in-place services. It would cost 20 billion dollars to end homelessness in the US – a tiny fraction the recent stimulus package. That cost wouldn’t be felt for a moment by the richest families in America. That American money is squirrelled away in their private bank accounts while people like Camila live how they do – well, I could go on and on.

What do you most hope readers take away from this book?

We have piles of data that tell us the scope of poverty in American – numbers that are increasing terrifyingly quickly, and which frankly were unthinkable before the pandemic hit our shores. But those numbers are so depersonalizing; every person who is counted as homeless, or living under the poverty line, has a past, a future, desires, hopes, a story. Every single one. Every one is someone to care about – we just have to know them. We have to live their experience with them. To feel their individuality. I wanted Camila to be both an individual in that respect, and also indicate the world of individuals, not graphs or statistics.

Solutions exist to our problems. They have been researched and recommended for years. But until we can truly feel life as it is lived for so many millions of Americans – indeed, as a human rights crisis, right on our watch – until we can internalize the experience, and care deep in our hearts, not just theoretically but actually -- feeling actual feelings about actual people – it’s hard to imagine that solutions will come to pass.

I wanted readers to feel, to experience, to care about a remarkable young woman, in all of her individuality and complexity, to take this horrific trip alongside her as I did, both to know her, and to begin to know the universal that surrounds her. So we can be moved to make significant change. Normal isn’t coming back after this crisis, and it shouldn’t. Normal was already a dystopia. This is our overdue chance to build a country that isn’t cloaked in shame. But we have to feel it in order to do it.

(I will be in live conversation online with my dear friend Mia Birdsong later today, 1-2pm PST. We’ll be talking about the art of building community, anti-racism, and so much more. If you’d like to join, please reply to this newsletter and let me know. I’ll get you an evite.)

Every newsletter you send has me going to the bookstore for another amazing read, and/or fired up to fight for another cause, and/or forwarding it to friends I know will love it as much as I do. I really appreciate your writing!