Maya and I were riding our bikes to the art store—a pandemic tradition that she asked to repeat on this sunny Sunday, when I caught some motion out of the corner of my eye. I turned to look and saw an older man hitting the sidewalk and heard him yell, “Help me!”

I turned my bike around. Maya followed. Once we got to him, I set my bike against a fence and rushed to him. His body was shaking. He was struggling to sit up, seemingly struggling to try to stand up, so I sat behind him criss-cross applesauce (as my daughters call it) and put my hand on his back. “Let’s just sit,” I said. “No reason to rush standing up. Let’s just sit and figure this out.”

As he leaned his weight into my hand, and he really did, and started to breathe a bit less haphazardly, I took stock of this man—his flesh-colored hearing aid, his long, skinny legs in jeans, his white wispy hair and the wild look in his eyes. I registered his fear and confusion. I felt deep in my belly that I could and should calm him. I said, “It’s going to be okay.”

Facing in the same direction, sitting on that sidewalk, my big hand on his back, we were united in trying to get our minds to catch up to the moment. Mine was working hard — “Is there someone I can call?” I asked him.

“No,” he said.

“Okay, maybe we should call to get some medical help,” I said.

“No,” he said, emphatically.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“James,” he said, immediately.

“And do you live close by?” I asked.

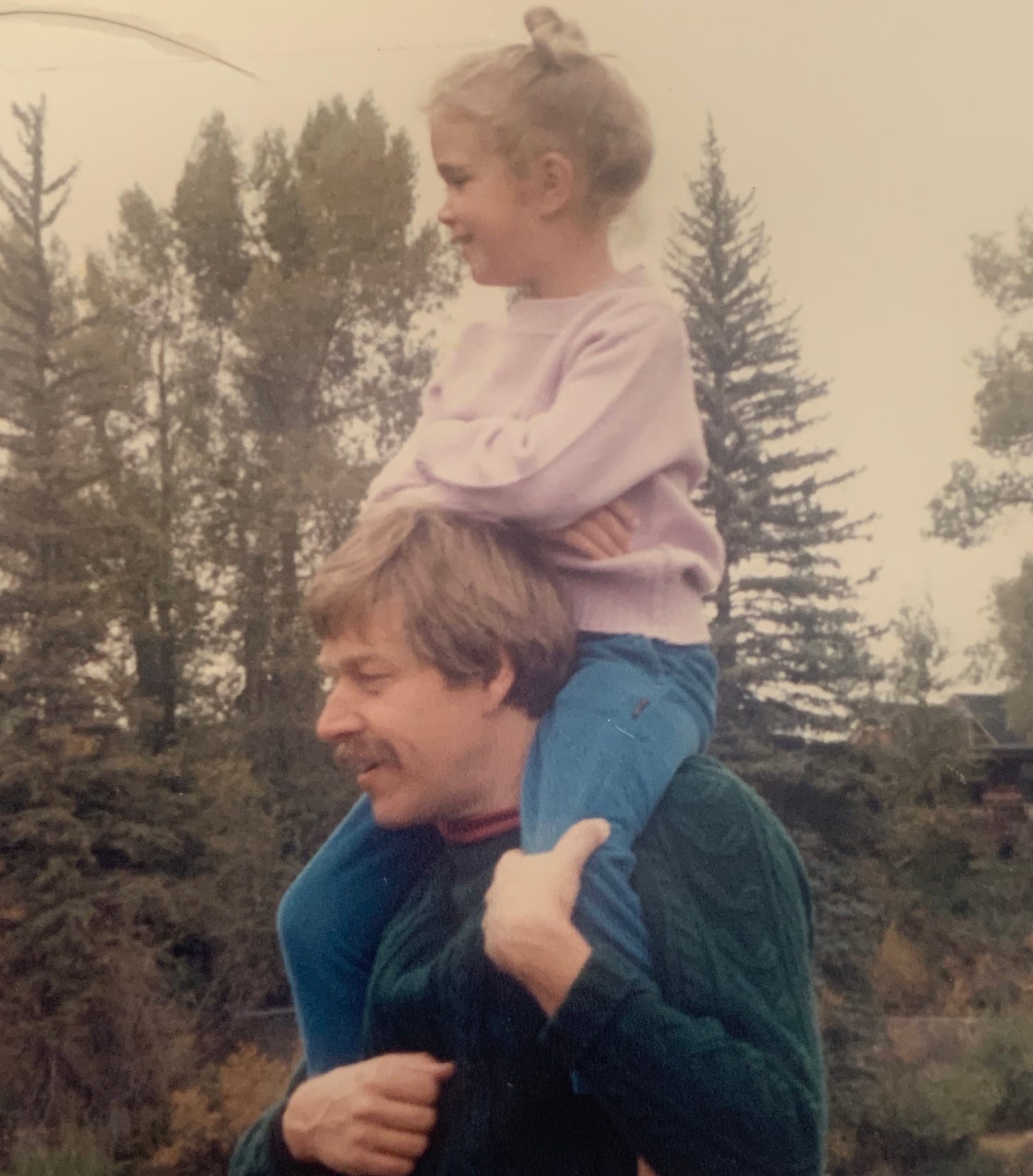

“Yes, I live…I live…my phone number…” Here he struggled to locate words to wrap around the reality he was trying to communicate. And I recognized the struggle. A realization crept in: this man, who is shaped and aged much like my own father, also has some form of dementia like my own father. I have spent the last few years learning to relate to my dad, whose mind has steadily lost the ability to locate words to wrap around reality. I am built for this moment and this man.

I sent Maya home and asked a stranger walking by with his coffee and his pitbull if he could help us. This was a two-grown-up job. He kindly came over and I explained the situation, adding, “I’m not a nurse.”

He said, “Me neither. I’m a lawyer.”

“I’m a writer,” I said and we both laughed—a brief respite of levity in the crisis. Two strangers, ill-equipped with anything but kindness for the moment at hand.

We decided to call 9-1-1. I was advised not to move him and to flag the emergency vehicle down when it arrived. “Is he speaking normally?” the dispatcher asked.

“I don’t know what’s normal for him. We’ve never met before,” I explained, registering again how intimate I was, physically, with this man, trying to soothe his panicked system, trying to be a soft place to land. But we have met before, I wanted to say. He’s my dad.

The lawyer and I talked some more with James and figured out that it seemed likely that he did live a few houses down and that his wife might be home, so the lawyer went off looking for her. It was just James and me then. I thought I should just get him talking, try to ease his nervous system into some normalcy. I said, “You have any kids?”

“Five or six,” he said. And again, I recognized the imprecise answer about something so seemingly definitional of a person’s biography. It’s an answer my own dad could have given.

“How about grandchildren?”

“A lot of those,” he said, a smile turning the corner of his mouth up.

“They’re a handful I bet,” I said, sharing his smile.

“Yes, a real handful.”

And for a moment we both smiled and looked up at the tree across the street, my hand on this stranger’s back, holding his weight, his skinny ankles still shaking, his mind full of familiar holes. My dad calls my youngest daughter “the little one,” as her name doesn’t stick in his brain anymore. He smiles and laughs with her, and also sometimes seems surprised when she turns a corner, even when we are weekend house guests.

I said, “So you live just a couple of houses down?”

And his brain connected to the proximity of his wife and the urgency of his situation and he screamed, “Help! Help!”

“It’s okay,” I said, “we’ll find her. Just breathe. Let’s breathe together. Everything is going to be okay.”

And he breathed and his agitation quieted. And his skinny ankles kept shaking. And the fire truck arrived with a half-dozen guys on it a few minutes later. I relinquished my post to the trauma experts. James’ wife appeared, walking, not running, I noted, towards us, and in this, too, in the expression on her face, I saw my own loving, weary mother. It is so much to love a man whose synapses are eroding.

Why am I telling you all this?

Because I have decided that my hand on this man’s back is the beginning of something. I am going to start writing more publicly about my journey with my dad.

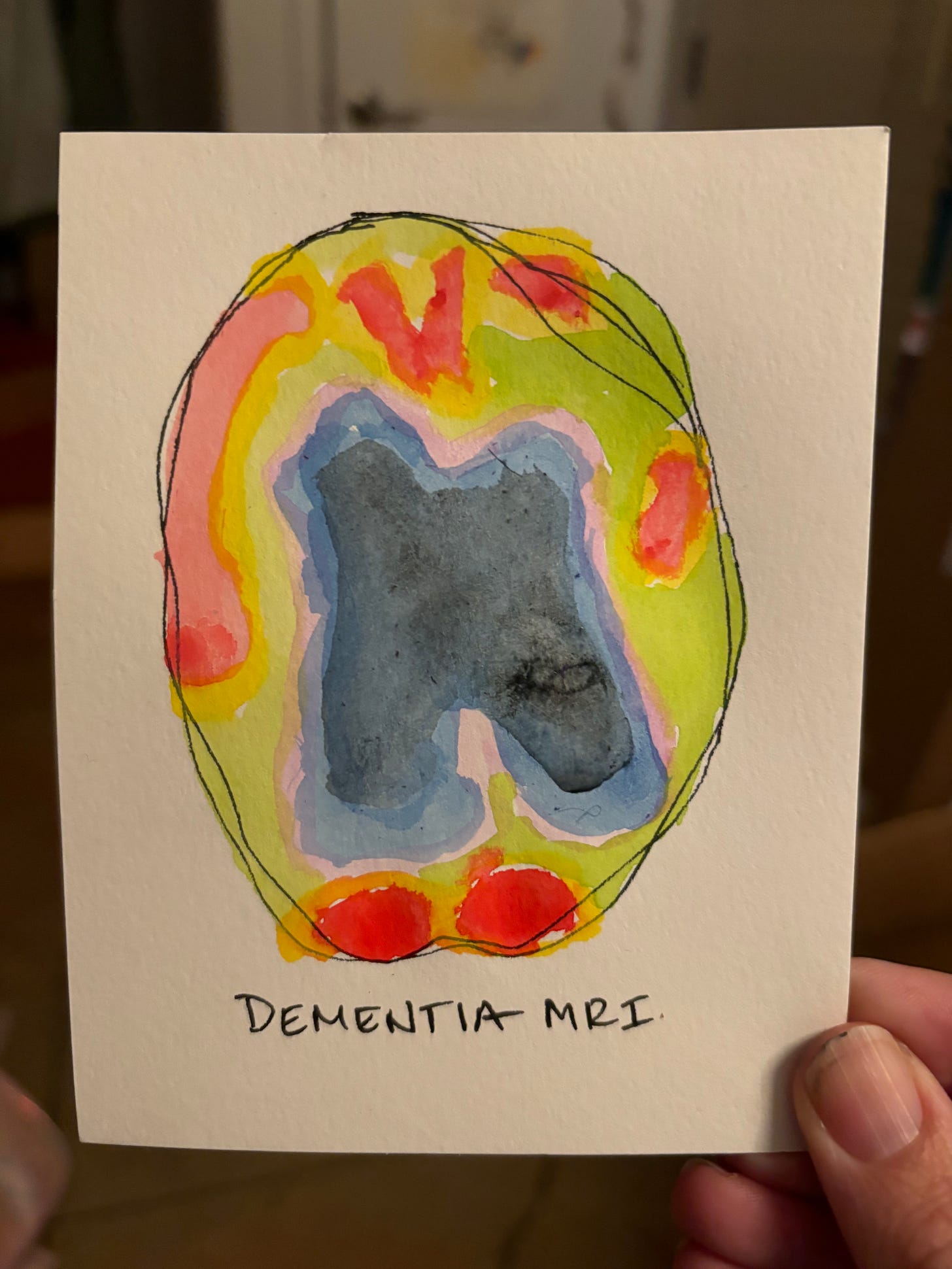

I haven’t done so for a long time out of respect for his privacy, and I will continue to care for what I believe he would and wouldn’t want put out in public, and will continue to be in dialogue with my mom and my brother about that. But for the last few months I have been sitting with a question: Is my silence publicly about my dad’s illness, and my experience of it, protecting him or contributing to the silence, shame, and stigma that surrounds this wildly common disease?

I’ve been slowly coming around to thinking my silence is no longer serving me, or the potentiality that putting words to my father’s loss of words, could be healing for others—all the daughters and sons and wives and husbands, the friends and neighbors, who love someone whose brain is fading, whose very essence is shifting, who requires new kinds of communication and care. The experience of my dad’s dementia, for me, has been one of profound loss, and also, it has been the most important experience—right next to birthing and growing my children—of exploring the human condition.

When I was a teenager, my dad and I used to do the grocery shopping together each Sunday, and as our minivan climbed the hill to King Soopers, we talked about everything under the sun—Buddhism and basketball, money and morality. These days, when my dad and I walk around his neighborhood together, I have learned to leave the theology and philosophy behind, and instead talk only about the concrete things right in front of us—that beautiful tree, that little crew of baby quails, that Little Free Library that has so many vintage botany books. At some point during these walks, inevitably, my dad turns to me and says, “Wow, you are getting so tall!” And I smile and remind him that I am in my 40s now and he is in his 70s and we both sort of stand agape at the passage of time and unwavering love.

In recognizing James, this fallen stranger, in recognizing the look on his wife’s face, I felt like the universe was saying, “Yes, write about it. Give people the recognition, the resonance, the gift of knowing they are not alone. Give yourself the gift of knowing you are not alone. Write about how dementia is a study in the human condition.”

So here I am, feeling a bit shaky like James, falling into your arms. My dad has dementia. It is terrible and often beautiful in totally surprising ways. I’d like to write more about it here. I hope that will be as healing for some of you as I know it probably will be for me.

I agree with others that dementia touches more lives than we realize, and talking about it in real time will be a gift to many.

Of the many gifts that come alive in your story is how you chose to slow down your day to recognize the speed of James’ world. It’s been my experience that slowing down is often the hardest thing for most of us. Living at the speed of love and understanding.

And in my own experience with my mom’s long dance with early onset dementia - there are many gifts our forgetful loved ones give us. They are not wasting away, but transitioning into fully lovable, if different, people.

Courtney, this is an important and impactful story, and I thank you for sharing it. I noticed a million precious details and meanings as I read, but what filled my hope bucket the most was towards the end, when you described neighborhood walks with your dad: "I have learned to leave the theology and philosophy behind, and instead talk only about the concrete things right in front of us—that beautiful tree, that little crew of baby quails, that Little Free Library that has so many vintage botany books." I liked how, amidst a season defined by loss and longing and change, those walks create an opportunity to tend to the moment at hand, the corporeal and concrete surroundings, the evolving experience of being together now. And now. And now. And now.