If you consistently enjoy this newsletter, if you open it almost every week, if you save it for a quiet moment or forward it to friends — consider becoming a paid subscriber. You make it possible for me to focus on this space and creating these conversations.

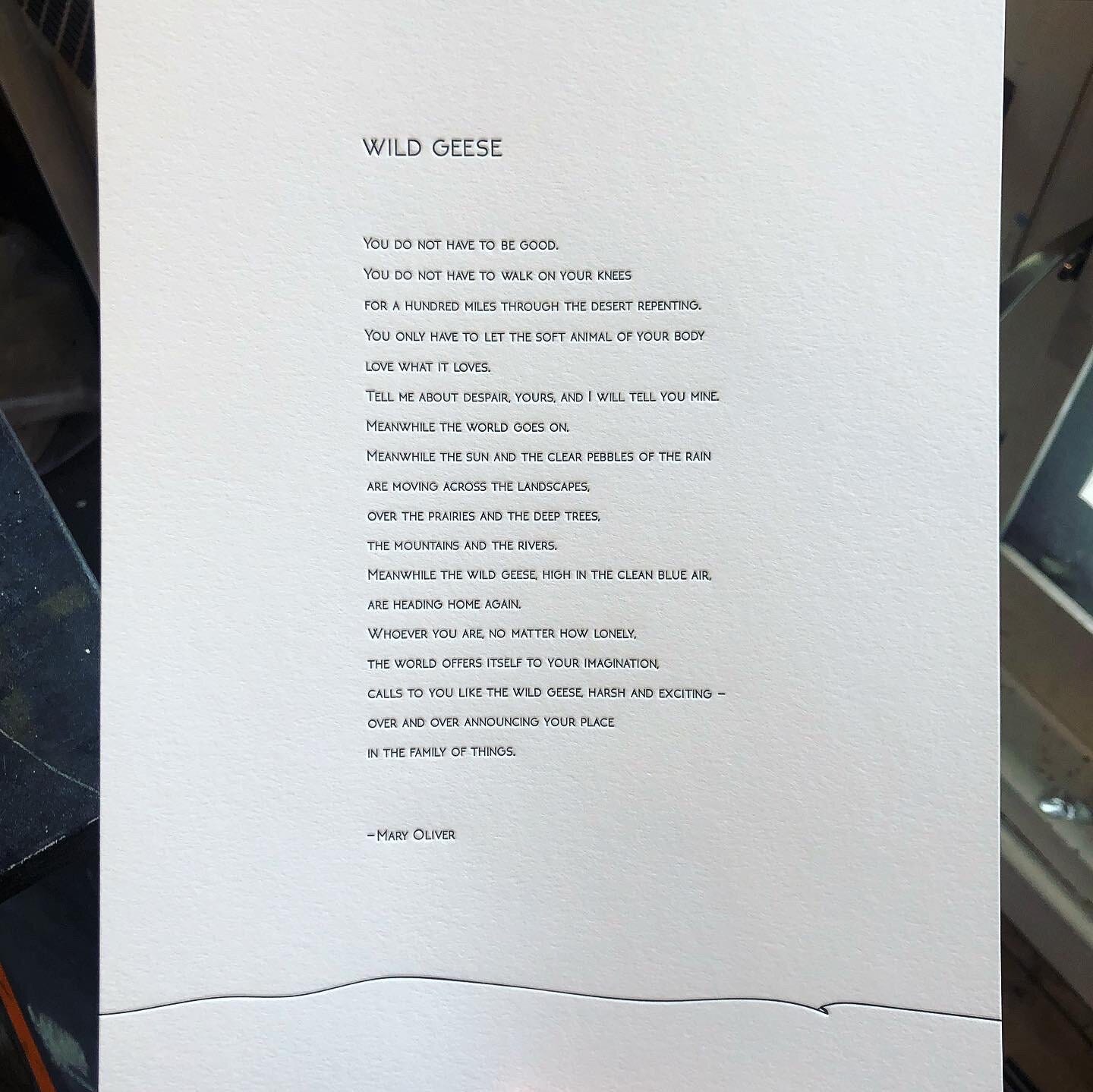

When my first book came out in 2008, my mom and I did a road trip from Seattle down to San Francisco—laughing, drinking martinis, and reveling in the beauty of the ocean all along the way. I would stop in bookstores and do readings. It was novel and ridiculous—a dream come true. One thing I remember vividly from that trip (other than the epic and inevitable hangry meltdown in Ashland) was that we memorized Mary Oliver’s poem “Wild Geese” along the way. You know the one—perhaps the most beloved of all of Mary’s beloved poems with the earth shattering revelation right from the start:

You do not have to be good.

If only I’d internalized that poem while memorizing it. If only I—today, in this moment, as I write these words—understood on some cellular level that being good was a basic goal, socialization’s boring substitute for liberation.

Being good is checkmarks and expectations, shallow breathing and anxiety in the middle of the night. Liberation is dangerously fresh knowing and acting on it—wholeness, breaking free from broken systems and cultures, hearing and seeing other people with as little assumption as possible, feedback, shifting, laughing, learning, emerging, quieting down, delighting. Being good is weighty. Liberation is lightness. Being good is attachment. Liberation is non-attachment. Being good is individualistic and, at its widest aperture, interpersonal. Liberation is collective.

I’m squinting at liberation these days. I feel it, then I lose it. I hear it, then it fades away in the presence of louder sounds. I know what it isn’t. It isn’t reading the radical book and talking about it a lot, but not feeling like it’s made it’s way into your behavior and bones. It isn’t talking yourself out of guilt or bludgeoning yourself with it. It isn’t perfecting your own ethical identity with self-satisfying tweaks and symbols. It isn’t fast, big, calculated, careful.

In a recent podcast I listened to at my brother’s recommendation, Dr. Bayo Akomolafe, a professor, thinker, father, partner, asks:

In what ways does being good become an exoskeleton that chains us to the ground with the presumption that the universe is morally coherent?

This, too, I am coming to understand, and oh it is so hard for me. Liberation does not assume moral coherence. I really, really crave moral coherence—in myself, in others, in systems. Liberation, instead, assumes flux and flow and backlash and unpredictable leaps forward. It isn’t afraid of dirty hands or feet, or generational timelines, or contradictions, paradoxes, and tensions. Being good wants a strategic plan and dutiful soldiers. Liberation wants heat maps and collaborators who surprise the hell out of each other.

Why am I telling you all of this?

I guess because I’m squinting and I’m hoping you’ll help me see.

When do you sense that you are trying to be good, that you are walking through the desert on your knees, and when do you sense that you are liberating yourself and others? How does the difference feel? How do you get more used to the lightness of liberation? How do you try easier? How do you not lose your childlike hatred of hypocrisy but shed your attachment to moral coherence? How do you make liberation tantalizing rather than goodness compulsory? And, of course, how do we parent, befriend, partner, teach, care for our elders in such a way that we prize liberation, not goodness?

If I am understanding correctly what you write here, what might help create an environment for such liberation is creating a culture around ourselves of forgiveness for error and imperfection.

We can start by becoming forgiving ourselves in place of holding grudges, or labeling, or making it hard for others to come out from under their missteps.

If we can forgive each other, maybe it will become easier to blame ourselves less and forgive ourselves more for well-meaning missteps.

One thing that really makes people tiptoe and avoid rather than entering any messy or ambiguous arena is the experience of having made an innocent error and feeling like it was never forgiven.

Learning to apologize sincerely and meaningfully when we accidentally hurt others is another piece of the work.

Perfect timing, Courtney. Several moons ago, I thanked you for one of your posts. Today, I thank you again.

I love Mary Oliver’s poetry, yet had not really assimilated the lines in Wild Geese that spoke of not having to be good and so on , nor pondered what those meant to me. The concept you raise of liberation and how it feels compared to trying to be good, and your thoughts on what liberation might mean in all its messiness and flux, resonated deeply in my soul just now. Your words will help me as I go forward into my 70 s (70 plus 2 days today) and do what I can to continue to liberate myself , and, in so doing, be better able to support my beloved husband, adult children and grandchildren in their journeys. And, perhaps, learn how to help our family to be together in loving, liberated ways.

I wish you love and liberation in your own life. Thank you for all you do to share your personal learning with others