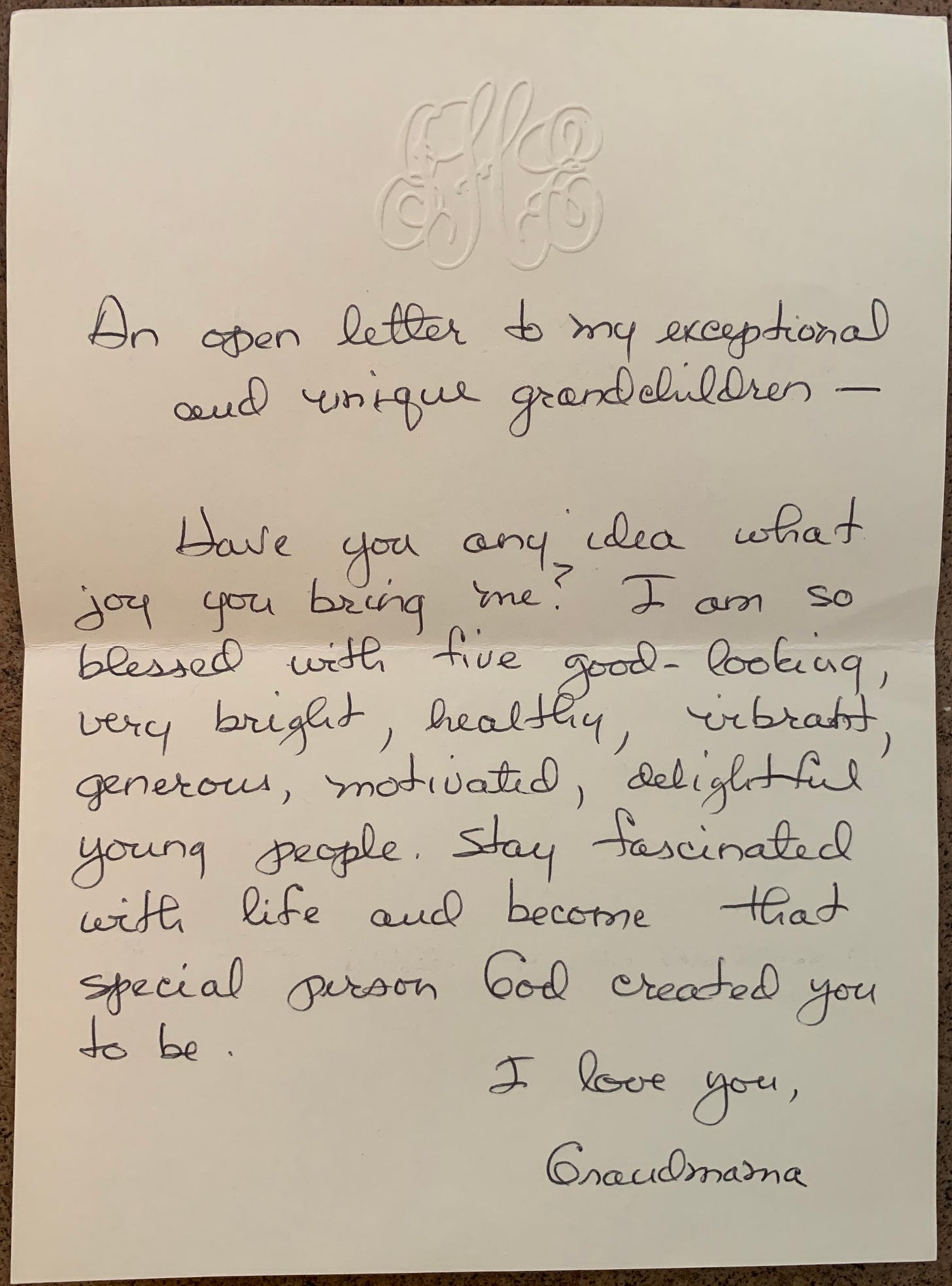

This a letter from Joan Hughes, my mother’s mother, penned in 1996 when I was 16 years old. I found it in our attic, amidst a bunch of middle school notes scribbled by hand on notebook paper, mix tapes, and love letters from my husband.

I have no idea what prompted my grandmother to write this letter. She sent it to my childhood home, in the town where she also lived. Why wouldn’t she have just handed it to me? I saw her all the time. I can easily recall so many things about her right now – the smell of the bologna she used to push through her big metal grinder, the way she’d safety pin the key to her condo pool to the skirt of her swimsuit, her mastectomy scar and her bulbous, arthritic knuckles, and the way she drank scotch neat. I sat mesmerized beside her on the church pew (she was a faithful Episcopalian) and stood next to her in the dark, staring up at fireworks exploding across the sky on my birthday (New Year’s Eve).

I knew Joan in a daily, corporeal way.

I knew Maryanne, my paternal grandmother, almost not at all.

For my entire childhood that was a contrast that I somehow didn’t think about. And then as I was graduating from college, they both died; Joan from pulmonary fibrosis and Maryanne from, well, I didn’t know. I cried for Joan. I had no tears for Maryanne.

And suddenly I was ravenous to know why. It led me on a strange journey of trying to unearth Maryanne. I interviewed my relatives—including her one living sibling, who gave me a plastic Albertsons bag filled with a haphazard assortment of her things. I wrote to the mental institutions where she was committed at different points in her life, asking for her files. I read a lot about the moment in history at which she came of age—a time when silence shrouded so many of the most painful moments in girls’ and women’s lives.

In some ways, my grandmother’s story is not unique. Like so many women of her generation, it involves an unplanned pregnancy, mental illness, economic precarity, and perhaps worst of all, unfulfilled dreams. My grandmother Maryanne wanted to be a writer. She never got to be.

I didn’t know her and yet, here I am, a writer–fully realized without having had any idea that I was living out a generational story until I started asking a lot of inconvenient and sometimes painful questions. Am I the “special person God created me to be”—as my Grandma Joan put it? I don’t know. I hope so. I do know I am a person created, in part, by the presence and absence of my grandmothers. One grandmother gave me thousands of words—penned on monographed stationary and said aloud over years and years; one grandmother gave me no words at all, but even still, her journey is in me and of me.

We all have these stories – the clashing of the personal and the political in our own ancestral lineages, the unspoken, unhealed, reclaimed, evolving.

I’m not someone who gets jazzed about going particularly far back in my family tree (my brother has been on an enlightening tear in this regard), but I find vital meaning in gazing just a few branches up. Understanding that my dad was raised with a tremendous amount of emotional and economic instability, that he carried around a lot of secrets and suffering, and that his mom loved him dearly and saw, in him, a second chance at a full life—all of that has made me a more whole person. I know that some of my own behaviors are not invented by me, but borrowed from genetic code deeply imprinted with the scarcity he and she both knew first-hand. That doesn’t mean I’m trapped in that story—and in fact my dad broke out of it in big, brave ways—but it does mean that it has shaped me.

There is a Celtic concept that I love–my way-back ancestors are Irish and Welsh, this much my brother has taught me–of a thin time and a thin place. It’s a space where the membrane between worlds is permeable. When you consider your lineage of stories, I mean unflinchingly face them and metabolize how they are of you, you enter into that kind of space. There is pain. A lot of it. There is also creativity and care.

Perhaps most importantly, there is a sort of sacred magic to the stories you find–synchronicities that are hard to explain in any rational way, time folding in on itself unexpectedly, and in all of that, the possibility of greater understanding and healing.

What are the important presences and absences that shaped you? What are the stories you have been afraid to know? How might it set you free to finally get up close to them?

If you do: listen for the permeability. Listen for the magic. Listen for the healing.

I’ll be exploring these themes this coming weekend with Esther Armah, Hannah Drake, and Loung Ung at the Omega Institute’s Women & Power conference. Listen in if you’re interested!

I've been thinking a lot about this this week. This month I am returning to Oregon as a speaker at the 30th anniversary of the national Wilderness Risk Management Conference. Thirty eight years ago the school mountaineering accident on Mt. Hood that I survived and which took the lives of nine students and teachers created a sea change in that field. Being invited to return there now to speak into my life from then -- an arc of embraced resilience -- is a deliberate step into that thin space, bringing story, reconnecting with friends and rescuers, inviting the likely possibility of some pain and also the sure certainty of care, creativity, connection. The living story of a survivor who still loves is where resilience and love are meeting. This is the pain that we can be grateful to be able to step into.

I’m itching to explore neurodiversity thread on my mom’s side - cleaving through my mom, me, my kids, my sibs, my sibs kids - but wholly unexamined by my vast maternal relatives; on dad’s side the grief/shame of my grandmother’s adoption (I recently came upon her original birth certificate from 1920’s. No father referenced - an immaculate conception?) and her adopted mother’s death when she was only 10.