A couple of quick announcements:

At 9am PST/12pm EST TODAY, FRESH, the speakers bureau and training organization that I co-founded is having our annual creative showcase live online. It’s free. It’s euphoric. It includes a live DJ, poetry, rap, talks, the amazing Sharon Salzberg and so much more. Register here!

The last episode of this season of The Wise Unknown is out and it’s fun. Meet my amazing producer, Golda, as I make her come out from behind stage and tell you all how weird and wonderful our process was. Hear voices from listeners and one of the key inspirations for the pod even existing. Learn more about how podcasts get made and how women work together when they have creative control and care for one another.

On with this week’s essay…

I held Kima, my badass old lady Tortoiseshell cat of the most elegant mix of black, white, and yellow, in my arms as she died last week. As the vet gave her the final injection, her little chin dropped about a centimeter, and I knew she was gone. The weight of her little body against my chest reminded me, strangely, of what it felt like to be pregnant. Though she had gotten skinny, the full surrender of her body on mine felt heavy, like our bodies had become one, or at the very least, like her trust in me and her ability to release were as complete as anything in this life, or the next, can get. It was a profound comfort next to the grief of it all.

The grief of it all! Losing a pet is such a strange experience—one of those things that so many people have deep stories about, and yet, we still don’t have a lot of societal structure or ritual around. And as with the death of a person, everyone processes the loss so differently. Even my little family was an amazing case study in that.

Kima, named after Shakima “Kima” Greggs, the police officer from The Wire, and I had been together since December of 2007. I was 27 years old and she was 5 months old when I picked her out at the shelter in Brooklyn. She was a spitting image of the Tortie I had grown up with, so it was definitely a love born of nostalgia. She used to sit on my chest and “make biscuits” for hours while I read in my first and only solo apartment—a one bedroom with built-in bookshelves and a bright purple bathtub. As she grew, and we eventually moved to Oakland, she became an indoor/outdoor cat and really embodied her namesake—a fiercely independent spirit who liked to bring us rats on our doorstep well into her geriatric age.

For me, losing her was all about maintaining her dignity. I wanted the Kima who lazed around the community garden and charmed all of our neighbors, the one who would flip little pieces of dry food out of the bowl so she could stalk then, rather than just leaning down and eating them, to go out the way she had lived—decisively, elegantly, and surrounded by love. So yes, of course, I am sad, but I have felt fueled by my desire to create this end for her.

And I did. She suffered for about a month (from what we would learn was a fast-moving bone cancer), but that’s it. As I walked to the vet a few blocks away with her in my arms, wrapped in a towel and blinking in the sunlight, just the two of us, everything felt so right. She was my witness for 17 years—seeing me through a break up and marriage, the birth of two kids, a bicoastal move. And at the very end, I became her witness—seeing her through the last breath.

While one might describe me as fairly stoic through all this, my oldest daughter Maya has been the opposite. The second I introduced the possibility that we might have to say goodbye to Kima, she burst into violent tears and hasn’t stopped since. She wailed the most basic and existential of questions over and over: “Why? Why? I don’t want her to die. I don’t want her to die.”

And I just had to hold her as I realized that she was waking up to the most central pain of being alive—loving and losing. As she screamed—why?—part of me wanted to admit—I have no idea! It’s terrible, isn’t it? It makes no sense? Let’s hunker down and never love a new thing or person again! But, of course, I know that’s not right or even possible. There is no good explanation for why other than because the alternative is to waste this one chance at fully feeling life and all the delight and doom of its connections. Why? Because this is what defines a worthwhile life—to love and lose. It’s the essential experience of our time on earth. If you don’t do it, you regret it. If you do do it, you swoon and suffer in equal measure. Better to do the latter every damn day.

Stella, my younger daughter, barely cried upon learning that we would have to say goodbye to Kima, and immediately got down to the business of ritualizing her death. As Maya was sobbing into Kima’s fur in her bedroom, Stella started building an offrenda in the hallway outside (thank you Coco!) made out of tiny paintings, little plastic doll food, and stuffed animals. She asked me to come into my bedroom so she could discuss the funeral plans without disturbing Maya— “I think we should ask everyone to wear black or lace, don’t you? And maybe we can play some songs and read some poetry. Do you have a poem about cats you can share?”

The morning of Kima’s appointment, I found Stella sitting on the ground cross-legged next to the cat, cutting something out of a big, orange piece of foam. “What is that?” I asked.

“A costume for her to wear when she dies,” she explained calmly. Maya let out another unashamed wail of a cry.

Stella chose to go to school that morning and be among her friends. We hear that she shared the day’s news with everyone and that her whole 2nd grade class had a big cathartic discussion about death and love and animals. When Stella couldn’t take it anymore, she went to the main office and burst into tears with Ms. Sandra, who called us to come pick her up and take her home, but not before she had a good chat with the principal about his own cat who had died. “Mom, so many people have been through this,” she reassured me when I saw her later that day.

Kima was John’s first pet and, so, his first pet loss. If he weren’t so socialized, he probably would have wailed like Maya. Instead he cried quietly, held his girl tight and told her it was okay to cry, took walks hand-in-hand, bought sweet treats for everyone, wrote emails of attentive gratitude to all those who had cared for Kima in the community, and collected all the beautiful pictures he’d taken of her over the years.

When faced with loss, some of us become focused and sort of dwell in the thin time and place of death itself. Some of us wail and ask the gods and goddesses and mothers why, why, why. Some of us ritualize and ornamentalize and collectivize. Some of us buy donuts.

And it’s all beautiful and good.

When Kima was gone, the four of us piled into the car and headed to the Redwoods—something we’d done most afternoons in the early days of the pandemic. We wandered around the ancient forest and talked about what we’d loved most about Kima. We shouted up to her as if her spirit might be floating around in the cloudy sky somewhere. We walked on fallen logs and noticed little forts that other people had built. We hugged a lot.

In this way, I guess, we all decided, despite all the inevitable and unavoidable losses to come, to just keep loving. Just keep witnessing. Just keep grieving in our own ways and then coming back together again and again and again.

In my experience losing a pet allows us to mourn out loud and more publicly and intensely than when a person we love dies. I don’t have a theory about this, just an awareness. Such a tender intimate piece you’ve written…thank you for inviting us into your grief…it feels a balm somehow. 💗

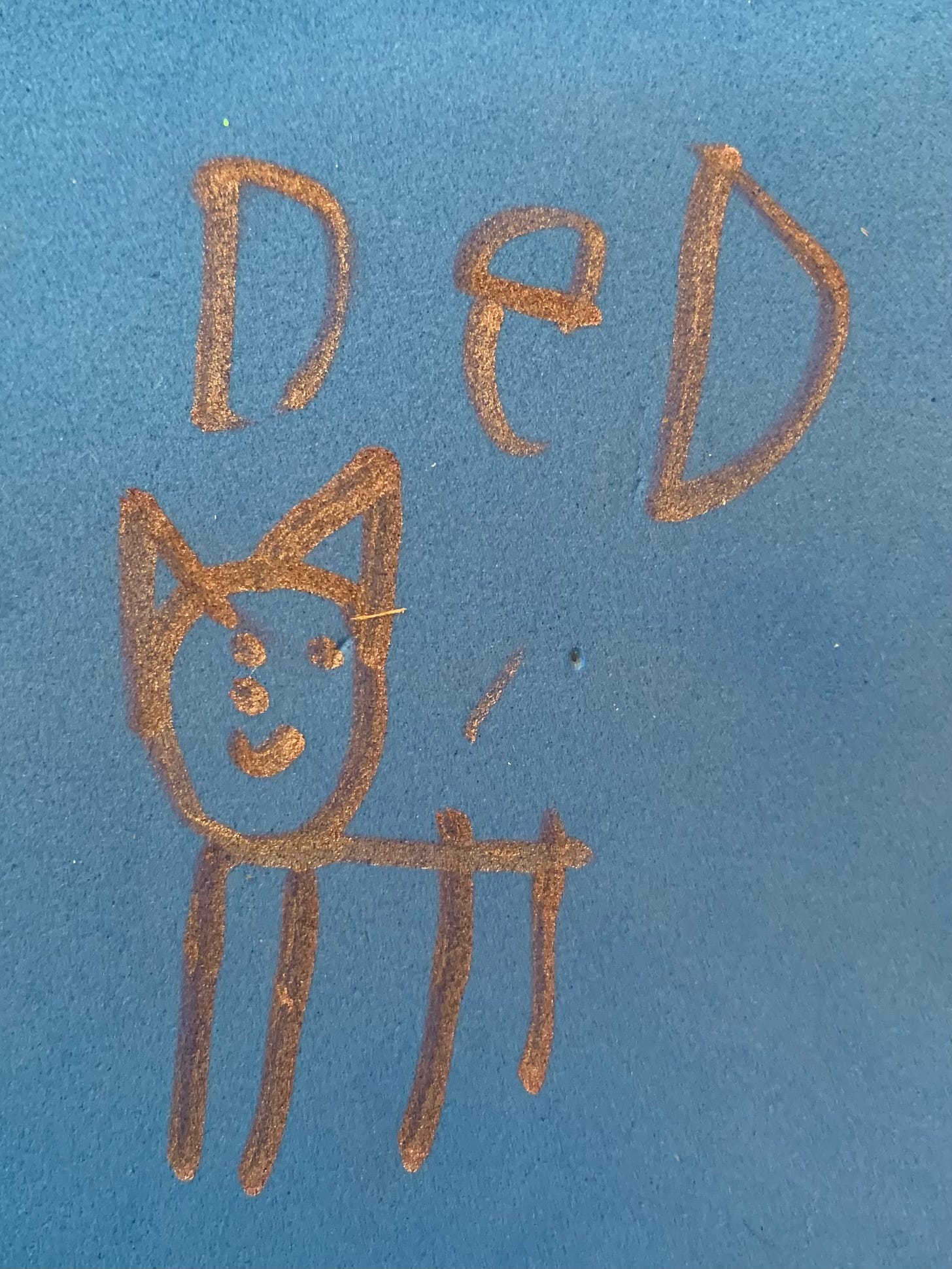

These drawing are everything. Sending you all so much love ❤️