I had a mentor once say to me, “Pay attention to who makes you jealous. Jealousy cuts through all the crap and tells you—on a gut level—what you want more for yourself.”

It was awesome advice and I’ve repeated it often. I’m not a very jealous person, but it turns out that when I feel it, it is a sort of beacon of what I want to be doing more of in the world.

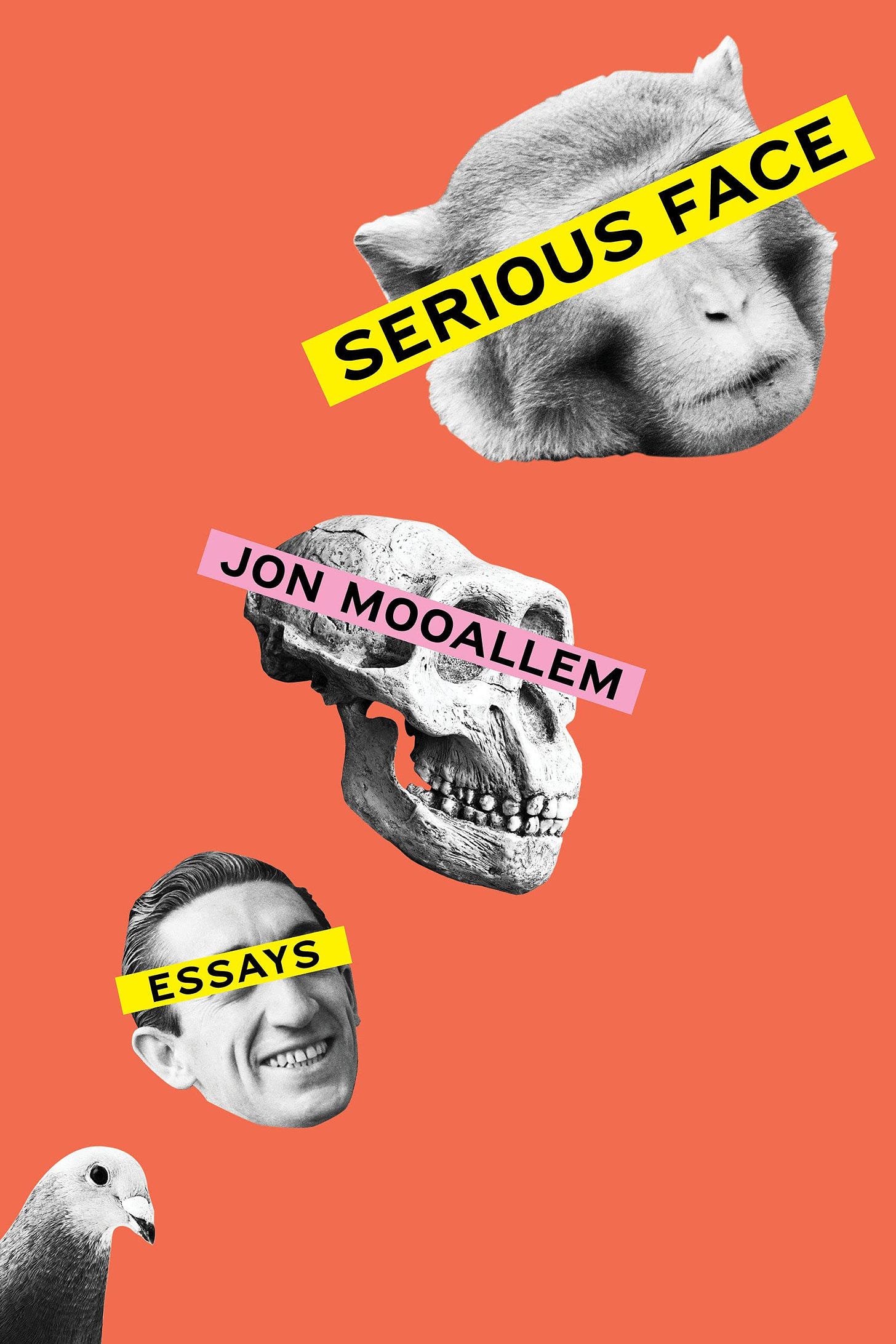

Well, folks, Jon Mooallem’s writing often makes me jealous. It’s infuriatingly good. His ability to pick the right details, to paint a sensory-rich environment full of the best foibles and sweetness of the human condition, his zinger sentences that seem like they were born from the most uncluttered head and true blue heart—-ugh, what an asshole. Or, no. What a beacon for what I want to do more of. (Thanks for the redirect mentor mine.)

Jon has a collection of his essays out now and it’s a wild, tender, funny ride. I am excited that he took some time to answer a few questions from 12,000 feet high.

Courtney Martin: How did you learn to be a journalist? Your writing strikes me as the kind that requires a boatload of painstaking reporting that you sort of make disappear to the average reader. That's an approach I learned some of when I studied under Ellen Willis at NYU, and found that it required an insane amount of tenacity, social boldness, and detail orientation. I love having done it, but I find the actual doing of it so laborious. You?

Jon Mooallem: Courtney! Good morning from my window seat.

I agree with everything you’re saying here: for me, reporting this kind of narrative journalism can be terribly exhausting and panic-inducing, and forces me to marshal levels of meticulousness and go-getter-ness that are virtually absent from every other aspect of my life. Plus, as someone who’s a little insecure and can feel awkward talking to people I don’t know well, reporting is like an emotional extreme sport. I am constantly fighting against a demented feeling that I’m bothering people or being obnoxious or an off-putting weirdo, especially on the phone. Still, I love it. It’s because I’m not necessarily suited to it--because it’s intimidating to me--that it feels like such a privilege to have gotten to do it for so many years. It’s the best thing for me.

I studied journalism formally at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, but we are talking about skills which I think one mainly has to learn by doing. That said, the value of journalism school for me was in having an expertly supervised and supportive environment in which to keep freelancing and practice those skills, struggling against these obstacles and taking risks. I started writing for the New York Times Magazine in 2005, when I was in my late-twenties. I was one of the youngest people writing for the magazine back then (things have changed!) and that made me work hard at the reporting-end of things: I needed to amass an almost impossible amount of information just to feel the confidence and authority to write any of it down. I still operate that way, though I’m not nearly as hard on myself in the process.

Anyway, this is an extremely gratifying compliment wrapped in a somewhat unanswerable question. Thank you.

You gravitate towards what one might think of crises—natural disasters, death, political clashes. Humanity, pushed to its edges, reveals something worth reporting—no doubt—but what about the mundane and ordinary? Have you experimented with writing less “edgy” stories?

Respectfully disagree! I’ve written all kinds of stories about almost ridiculously whimsical or mundane-seeming narratives—realities that feel somewhat sideways. (See, for example, the essay about an eccentric Frenchman who decided to build his own town in the middle of the desert and declare it the “Center of the World,” or the piece about a global society of amateur cloud-enthusiasts dedicated to the appreciation of clouds.) It’s gratifying for me to pursue odd-ball stories like these with the same intense and earnest curiosity and, in the best cases, wind up somewhere deeper and more insightful than you might have imagined possible. I think going through that process with stories so many times has made me more appreciative and open-minded in life in general.

Why do you think that so many of your characters are men?

It’s my own unconscious bias--becoming more conscious every day. It’s probably a symptom of bigger societal imbalances, too. Meaning, while I started out (naively) thinking of myself as simply prowling around for captivating human dramas, maybe men are just given more opportunities, and afforded more latitude, to wedge themselves at the center of dramas which wind up making enough noise in the world to catch a journalist's eye. (For example, in Serious Face, I write about someone who concocted a multi-million dollar pigeon-breeding ponzi scheme to bilk Canadian farmers; I don't think anyone would be terribly surprised to hear that this person is a man.)

So for me, the subtext of your question is really: do I have a responsibility to push against those biases? Of course I do. And I try to.

My last book was centered very intimately around one woman’s work and life, as was one of the three sections of my first book. Frankly, this troubles me more when it comes to people of color, who I’ve definitely written less about.

But the thornier question for me is:

How relentlessly should I be pushing against those biases--how highly must I prioritize that push, and at the expense of what else?

This is something I’d honestly love to discuss with you in a different format--like, maybe an actual back-and-forth conversation!--because I think you’re really thoughtful about these questions, whereas they often bring up a lot of complicated and seemingly irreconcilable ideas for me. [Yes, please! -CM]

I’ll give you an example: in one piece in the book, I write about the Camp Fire, which destroyed the town of Paradise, California, in 2018. This was a situation where the New York Times Magazine had sent me down to Paradise, on extreme short notice in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, to find some way to write about an almost unthinkable catastrophe. When I got there, it felt like pure chaos; I was crazy intimidated, operating far outside my professional comfort zone, and worried that I'd fail at producing anything of value at all. But one afternoon, I managed to meet a woman named Tamra who, like so many others, had endured an absolutely gut-wrenching series of events while evacuating the town, and who’d also filmed almost the entire morning on her phone. The footage was excruciating to watch--all the horror was preserved there. I knew that, with her documentation as raw material, I could write a story about a disaster--and therefore, about climate change--that would recreate the absolute terror that one person felt.

And yet: a lot of that footage showed Tamra screaming, crying, not knowing what to do. Ultimately, she was taken in by another driver—a window washer named Larry—who essentially took responsibility for her safety and got her out of town. There was something poignant to me about how each of these people responded to the crisis; both reactions seemed blameless and real. Still, I worried about the implications of writing a story in which a woman panicked and a man came to her rescue. I wrestled with that for a long time. But the reality was, this was the most powerful, true story available to me to tell and I couldn't imagine abandoning it. So I worked hard to portray the idiosyncratic humanity of that particular woman and that particular man and the unfathomable distress they were experiencing so saliently that it would be difficult for a reader to shoehorn all that specificity into some unhelpful stereotype or fairy tale. I was being given eleven thousand words in one of the world’s most-read magazines, and I feel like I delivered something that not only depicted a climate disaster in an uncommonly chastening way, but also allowed people a rare opportunity to simply look closely at two other human beings.

My point is, I think I’ve often been narrowly focused on finding a story that I can tell with enough intimacy, sensitivity, nuance and compassion to elevate the humanity of everyone involved. Other concerns—like the one you’re asking about—typically become secondary. I’m not sure how full-throatedly I want to defend that approach, but I do know it has a lot of value.

In the introduction, you say that you found a common thread in these essays—which span about a decade of your career—to be “Why are we not better than we are?” Having asked it in so many different ways, through so many different people bumping up against one another, do you have any answers?

What can I say? More and more, I’m just convinced that we’re all far more flawed and inept than we tend to think we are—that we get impossibly confused and turned-around all the time, that our best intentions often curdle or come undone, that the world we’ve built up is almost unintelligibly complicated and tarnished, and that the excessively messy alchemy between our thoughts and feelings doesn’t always spit out something shinier.

These are just lofty, overly-caffeinated ways of saying “Nobody's perfect,” which is also (I think?) the core teaching of most major religions. Still, we can imagine perfection and strive for it. So there’s tension there. It’s endlessly fascinating to me to see what we do with that tension and those imperfections—both ours and others’: how we survive within them, slog on in spite of them, overcompensate, or warp under their weight. It’s also totally possible I am just projecting my own psychology onto the entire human race.

You have all the money in the world to do exactly the kind of reporting and writing your heart/brain desires at exactly the pace and word length. What is your next project?

An attorney friend recently told me about something called the “social history” section of a habeas petition. As I understand it, it’s a kind of book-length, exhaustively researched biography of someone who’s been sentenced to death, offered to the court in an attempt to overturn or commute their sentence. Even while typing this out, I’m realizing that money probably isn’t the obstacle. Regardless, lately I’ve been wondering if I should be writing those.

We are donating to Would Works in Jon’s honor. Pile on if you like!

And hey, if you haven’t already, subscribe. It’s free. Or not. You choose.

I love this interview. I’ll add that Jon was a writer in college I admired. He was the editor of our campus lit mag and though he eventually gave up on poetry, he was at that time a poet. And an excellent one. For sure that background colors his journalism, those just right details in concise and well timed ways.

Wow