Maya, my six-year-old, has been working on a family tree the last few days. She’s been sorting through piles of photographs of people we love in a kitchen drawer, cutting out her uncles and aunts and cousins, and taping them on a giant piece of white paper. She was working on it yesterday morning when I told them that the reason they were off of “school” was because of Indigenous Peoples Day. Maya told Stella stories about the traditional skirt she made in transition kindergarten and the clip of Pocahontas they got to watch.

I tried to insert a little reality into the conversation--telling them about the way in which White people came here and stole land from the Indigenous people (in our region, it was primarily the Ohlone people) and brought disease and a lot of violence. I talked a bit about the extraordinary occupation of Alcatraz and contemporary Native people who still live in Oakland, write incredible books etc. “And White people stole their houses?” Stella asked.

“Yes,” I said. “It was really wrong.”

Stella was incredulous. She gets fairness in her four-year-old bones. “They should give the houses back,” she said. And she wasn’t wrong.

Part of what White Americans are tasked with doing in this moment is figuring out how to do what my girls were doing at the kitchen table while eating their Mickey Mouse waffles--rewrite our own histories and reckon with the pain therein, relearn our American history and figure out how to repair and, at the very least, give some things back. We are straining to connect our own family trees to the mythic violence and brutality of America’s “founding.”

It’s destabilizing work on so many levels. My mom, brother, and I have been reading My Grandmother’s Hands by Resma Menakem--a book about racial trauma and healing. It led my big brother to go down some wild rabbit holds on ancestry.com and what he’s finding--besides amazing names like Jabez, Faulk, and Hannaniah--is a whole lot of trauma and violence. He’s mapping some of this trauma onto his own emotional landscape--his vigilance, his fear of abandonment. We had a beer the other night and talked about it on zoom; the tears that welled up in his eyes felt like they sprung from ancient streams.

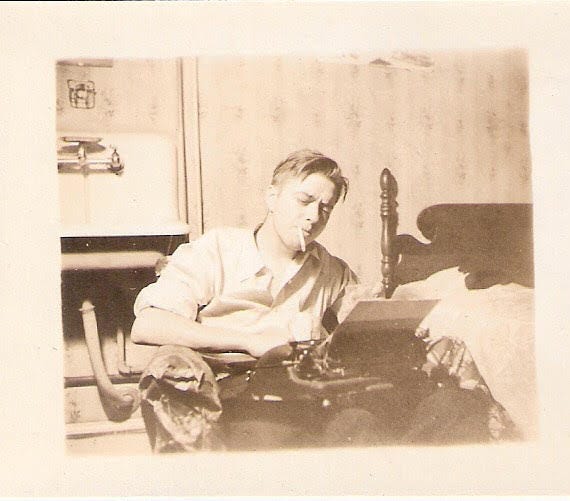

My great uncle Dub, who was both a heart surgeon and a screenwriter, apparently? And looks a lot like my dear ol’ dad.

I tried to sense, in my own body, whether or how I felt connected to these stories--an ancestor who fought beside William Wallace in occupied Scotland, another who came to America as an indentured servant from Ireland, my paternal grandfather who had upwards of 20 brothers and sisters in abject poverty in Illinois. The most well-documented lives, of course, are the men’s lives—a great, though unsurprising disappointment. These people’s genes have informed mine. Their life experiences, even, got written into my genetic code; science now tells us this. Figuring out how to relate to that--not medically, but morally--is the work of our time.

There is a lot missing on that site, but there is a lot that has been hiding in plain sight. In fact, I grew up with a framed copy of that indentured contract on my kitchen wall, and yet, we never really talked much about it, never explored the implications for our family or this country. It was just a worn and torn document with a cool seal.

This is the way of so many White families. We have trauma all around us, but never get around to talking about it directly.

And our behavior is fractal. Our way of talking about our family history without actually talking about our family history is our way of talking about American history without actually talking about American history.

We have to stop doing that. We have to start wrestling with the real blood lines and broken promises, stolen land and fallen trees. We have to start connecting the dots between the trauma we’ve endured and the trauma we’ve caused.

My brother tells me: “The Dakota stress that the land shouldn’t belong to us, but rather that we should belong to the land. Perhaps we have to belong to ourselves first?”

Nothing like an Uncle Chris hug.

We can’t face the profound unfairness of what our ancestors wrought if we can’t talk about it with our children. We can’t repair until we’ve told the truth. We have to start saying it out loud, to each other, the dark and the light intermingling so we can make ourselves whole again. Make this country whole again.

Wonderful, wonderful. This feels so pertinent and personally relevant...Resma's book (as well as the work of Dr Daniel Foor, Ancestral Medicine) sent me into ancestry.com, too, with thanks to all the people who've populated that, so I could just learn a few names and fill in many blanks. Suddenly, history comes alive in ways it never did in school - me wanting to read between the lines of the tree and understand the context... It makes me wonder if this great pause, this pandemic, is an invitation to step into this kind of work... like all the ancestors are holding some kind of space and urging us, come on now, step up, it's time to clear the air and replenish the soil and awaken some profound intelligence that is latent in our DNA, if we can just move and clear the great blockages of wounds that must not be spoken of... that have lodged in our bodies for generations. Thanks Courtney for your wonderful and generous explorations. I always feel enriched by you.

Don't forget Silence Allen or Salome Stonecipher!

I had a conversation with a neighbor yesterday. He was concerned about me voting in person, thought there might be trouble with aggressive militia. I told him my grandfather joined a militia at age 12, for his own complicated reasons. Knowing my history allows me the possibility of real conversations, even with people who don't currently come within light years of my worldview. Whether you're escaping a violent alcoholic or running into the arms of an amoral enabler masquerading as president, there's trauma at work. Seeing how we share trauma and how we might metabolize it (rather than bury and multiply it) is our only path to wholeness.