On a recent road trip along California’s gorgeous coast I saw this sign and it made me laugh out loud.

I felt like the sign was affirming that, yes, there may be harmony in a town with a population of less than 20 people (maybe), but anything above that is a bit of a pipe dream.

I’m a stan for community on every level. I think that almost all of the world’s problems—climate change, economic inequality, violence—can be remedied with some form of community, which is also to say, a return to thinking collectively and relationally. As Dorothy Day wrote, “We have all known the long loneliness, and we have found that the answer is community.”

Communities slow us down in a way that is actually in line with human flourishing. The more heterogeneous they are, the more abundant they feel; there are just so many different gifts and realms of experience and mindsets to be nourished by when you live, work, and learn alongside people who are—eureka!—not you, or even like you. Community gets you outside of your own echoing headspace, provides gentle light on dark days, and is chockfull of delights you could never predict. (Last week alone, I ate oatmeal raisin cookies that were baked by a neighbor who borrowed my eggs, was relieved of bathing my kid on Sunday night because she hopped into some else’s tub, and passed my print newspaper on to another household after I finished reading it.)

I am a bit of a community addict—I’ve got my cohousing community, my school committees, my women’s group, my giving circle, my organizing chapters. If there’s a group of tired parents circling up some folding chairs and a Trader Joe’s-heavy potluck spread somewhere in Oakland, chances are, I’m there, too. Probably facilitating (though I’m trying to do less of that). Definitely making people listen to a poem at the end, even if they don’t think they’re poetry people (only plan to do more and more of that).

But listen: I love my various communities and all of our carrot sticks and hummus, and yet, I have zero delusions about how harmonious they are. That’s become extra clear to me as I’ve read people like New York Times columnist David Brooks write about community as if he just discovered it or Ezra Klein and Dan Savage talk about community with a romantic swoon. I realize—these dudes are ingénues of community.

No shade on them (well, a little on David Brooks; I like Ezra and Dan). I was once a community ingénue myself. I’d grown up watching my mom—the OG community builder—gather and gather and gather, but I never really got into the nitty gritty with her until much later about all of the labor and heartache that went into that. Sure I lived in cramped New York apartments with 20-somethings writing passive aggressive notes about the dirty dishes on white boards, but nothing more ambitious than that. My sobriety about the challenges of community life have been hard-earned over this last decade or so of really leaning into the collective.

I was recently at a gathering of local parents who are fighting for integrated schools. We were sort of working ourselves up into a lather about all the systemic and cultural problems--the burned out teachers, the hungry, unhoused kids, the gossiping parents, when one of our members, a former school teacher and a psychologist, said: “I just have to interject here--has anyone ever been part of an organization or a large decision making body that didn’t have these challenges?”

We let out a cathartic laugh. She went on: “This isn’t just a school problem. This is a human problem. Schools are weird organizations when you think about it. They don’t really work for you, but you’re a client...kind of. Your kid is actually the client. And there is this incredible emotional investment.”

Oh, right. Duh. Public schools are basically the most complex kind of community there could possibly be--a crew of people from different racial, religious, and class backgrounds, who didn’t choose one another, coming together with pathetically limited resources to try to care for one of our most precious, insanity-inducing assets: our kids. Some eggs are going to get broken with that collective recipe.

If I had to pick a word to sum up the central struggle in community it would have to be projection. It is so hard for us to see ourselves accurately, much less another person accurately. When a group of people get together, well, it’s like an invitation to project our misperceptions, our unanswered desires to connect and be seen, our need for control, at a much larger scale. We instinctually try to figure out where we fit in the whole (Am I leader? Am I the last one to volunteer? Am I emotionally safe here? Am I the person who is willing to say when I don’t understand something or think we’ve gone ethically astray? What does that say about me and my identity?) and then bump up against one another’s often clumsy figuring.

Some of this is about facilitation. It can certainly be helpful to create some ground rules in community, to encourage people to “step up, step back,” for example. But these kinds of helpful agreements are not a cure for the wounds that people bring into the room. Many have been festering since childhood; that’s no match for a poster paper filled with cheerful intentions.

My neighbor Kate calls community--in our case, cohousing--the ultimate “adult development project,” and I think she’s right (Kate’s an awesome writer whose work you should check out). Ours is based on the premise of “radical hospitality”—the notion that all are truly welcome, regardless of the shape they show up in. I’ve been most deeply moved by community when I experience it as a place where no one gets thrown away. But that is also what makes community so excruciatingly difficult sometimes. You can pass the mic, take a breath, take a break, but if you’re in real, messy, committed community, you have to jump back in with a new strategy for how to co-exist and collaborate without destroying one another. Probably the healthiest communities are not those where no one ever burns out (it seems like that’s just inevitable), but where people take turns burning out and building their stamina back up.

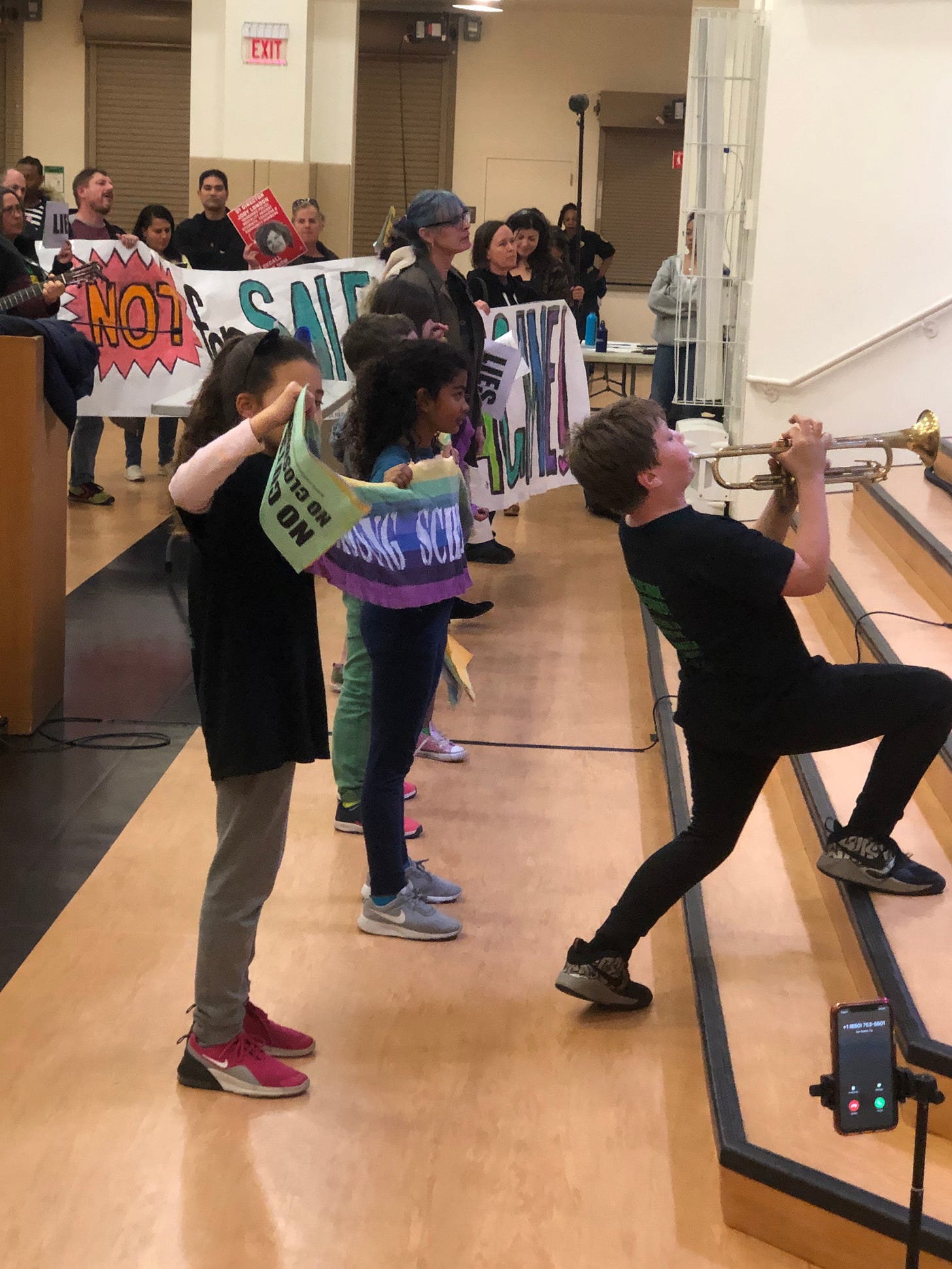

That might sound dramatic, but if you’ve lived or worked in deep community, you know that it can get pretty dang dramatic. I’ve spent a lot of time trying to understand why that is. I think it has something to do with the shadow side of non-hierarchical structure--when people can’t look to an organizational chart to find out what their status is, they tend to informally try to figure it out by bumping up against one another in sometimes harmful and annoying ways. Egos are less restrained. Savior complexes metastasize. Control freaks let their flags fly. Just tune into your local school board meeting if you want a toxic taste of what I’m talking about.

I think it also has something to do with motive. In a for-profit business, the motivation is money. People come to work, as Karl Marx taught us, for all kinds of reasons that have nothing to do with money. But at the end of the day, you’re collecting a paycheck and profit is the collective north star. In a community, the motives can be all over the map. That makes for a rich and fertile ecosystem, but also a lot of confusion.

It begs the question: when and where did you experience truly functional, interdependent community? (Even if it was just for a season.) No seriously, tell us in comments. What do we have to learn about why and how that community thrived? Let’s make one another smarter and more harmonious beyond population 18...

I love this reflection on community, Courtney -- and esp the photo of the kids self-organizing. My best community experience was back in 1996 when I joined a startup chapter of a national organization then called F.E.M.A.L.E., Formerly Employed Mothers at the Leading Edge--or Loose Ends. It was based on a book called Sequencing, with the idea that we could do it all as women, just not all at once, and as the title said, we were mostly career women new to being stay-at-home moms and also mostly all transplants in a new suburb of Denver in the tech boom years. Within a few months we had self-organized into subgroups from gourmet dinner clubs, playgroups, investment group, newsletter committee, and care group, and more. We had monthly meetings with guest speakers. The main rule was no politics, which feels so ironic in today's world. Within a year we were in the thick of supporting each other through cancers and infertility and tough pregnancies, and all the rest of human stuff. And more than 25 years later these are still the women I consider indispensable for my heart. We weren't very heterogeneous in terms of skin color or socioeconomics but we came together from all over the US. Did we thrive because we were similar, or starved for a place to see ourselves as whole and more than moms, or that we committed to each other on a regular basis. I don't know but I'm so grateful for the season of support and the ongoing connection.

I live in a small town that seems like the best place in the world to me because of the sense of community. It is a town where volunteers keep the animal rescue kennel, the recycling center, hospice, library extended hours (volunteers work the circulation desk so we can be open until 7pm four nights a week), fire department, cemetery and special events alive. People here want to live in a good place and they know they have to step up to make that happen. When disaster struck two years ago good folks took care of each other and helped in recovery. BUT we can be mean to each other and sometimes downright hateful. I cry to think that. People run for public office with good intentions and resign because they can't take the hate they give. At times, when all seems too hard, it always helps to gather again with friends and reaffirm and advocate for the values we live by. I wish it wasn't so messy and hard.