'Every word is half someone else’s'

5 questions for academic, journalist, and observant friend Lissa Soep

There’s not much that I value more in life than friendship and words, so to find out there was a book about the undying power of the intersection of the two made me very excited. And then I read it—this quiet, unusual, new book, called Other People’s Words—and found my excitement founded and then some.

It made me reminisce on critical friendships in my own life—some everlasting, some dead before their time. It made me hear things coming out of my own mouth in new ways—my dad’s trademark “Is that right?” and my dear friend’s favorite term of endearment and empathy “oh bunny.” It made me wonder about my own legacy of words in the people I love—what I have I said or not said has been absorbed into them?

I was grateful that Lissa Soep, the thoughtful author of this provoking, original book, wanted to do a Q&A. Meet her now…

Courtney Martin: This book is about the way the world of a friendship endures beyond death, in part, because of words. When did you know you’d write a book on this?

Lissa Soep: Around ten years ago, two close friends of mine died, Christine after a long illness, Jonnie in an instant. I was having a hard time with these losses. I longed to keep talking to my friends, to keep hearing from them. And then I noticed something that brought me real consolation: that their voices were still here, all around me and within me. This realization is what got me started on Other People’s Words.

Sometimes, I would come across concrete traces of their voices, like when Jonnie’s wife, my friend Emily, played his phone messages for me, one after the other — “Hey Sugar, it’s me, just calling to check in with you,” “Hey Sugar, sorry I’m not there” — and it was almost as if he were speaking from two dimensions at once, before and after he died.

Other times, I heard my friends’ voices rippling through my own words. Whenever I would read something out loud, my voice took on a certain cadence. My kids teased me about it. They called it my “teacher voice” and rolled their eyes. But I knew where this voice came from. It was Christine. She and her partner Mercy taught high school English, and they were always reciting passages from killer student essays or poems they loved. Embodying Christine’s intonation, I felt her companionship, a presence I’d been missing.

This is something so many of us do, in a running dialogue with the people we love who are gone. I wanted to notice and name this experience, to understand how it works and feels. And to do so, my mind went to an unlikely place. I found myself unable to stop thinking about a philosopher of language I’d studied back in grad school: a Russian critic named Mikhail Bakhtin.

Dialogue was Bakhtin’s obsession, , especially when it appeared in conversations within people, not between them.

“Our speech is filled to overflowing with other people’s words,” Bakhtin wrote.

Every word is half someone else’s, he believed, and we have the capacity to speak in more than one voice at a time — a process he called “double-voicing.” It’s like when a singer covers another artist’s song and you experience both of their voices at once, a devotional chord. Our everyday words can be like those songs, brimming with voices, past and present, unruly and inexhaustible.

These ideas were so helpful to me, and I wanted to share them. I suppose that realization was another moment when I knew I wanted to write a book that brought me together with my friends and explored this understanding of language, which had felt like a revelation.

This is somehow an “academic” book while remaining deeply human, accessible, and even light, in the double meaning (airy and illuminating). How did you do that?!

Thank you so much for putting it like that! My formal training is as an academic, and I’ve worked in journalism for decades. Writing this book, both roles served me well on lots of levels, but I also had to unlearn habits that got in the way of my highest hopes for this book. I knew that I wanted it to be moving, both in its narrative pace and its effect on readers. I didn’t want people to come away only knowing something. I wanted them to feel something.

Your reference to “light” really strikes me. Years ago, I shared a much earlier draft of Other People’s Words with an amazing writer, back when it was a stack of printed pages. “Holding this little book,” he wrote after reading it, “is like holding a new element. The weight is uncanny — at once light and then very heavy.”

At that point, the manuscript still needed a lot of work, and trust me, he said as much! But his image of light and heavy really guided my revisions. It’s partly why I shaped the book as a series of small moments and sparse pages versus weighty chapters. I hope this structure gives the story a kind of page-turning energy even when it visits dark places. [It does! -CM]

I also studied other books I admire for the way they gracefully introduce ideas without ever bogging down or derailing the narrative. Chloé Cooper Jones’s Easy Beauty is one example. I realized that Bakhtin needed to be a character in the story and not just a citation. He needed to appear with his own loves and losses, his own circle of intimate friends, his own lines of dialogue weaving in and out of the story.

I’ve just read On Vanishing by Lynn Casteel Harper [Q&A to come!], which is theoretically a book about dementia, but is about so much more. I think you’d love it. In any case, she writes about how we mourn the version of our loved one who didn’t have dementia--the “gone self”--while trying to get to know the new version “the not gone self.”

But then she goes on to point out that that’s really true of all of us--we are a layering on of so many versions of ourselves that we’ve been and are no longer. I got this sense, reading your book, that friendship is often the line drawn between the gone and not gone selves. Our friends have witnessed us at different ages and seen our evolutions. Does this resonate for you?

After you sent these questions, but before I answered them, I read Harper’s book. Wow. Thank you so much for telling me about it.

“I saw her roundly,” Harper wrote about watching Victoria, a woman with dementia, receiving a blessing from a nun. I love this idea of seeing — and being seen — roundly, “as a person in dynamic motion, circling an ineffable cause.” Without glossing over the specific realities of living with dementia, Harper invites readers to imagine all lives “as conglomerations of the ordinary and the peculiar, the fragmented and the whole, the present and the vanishing.”

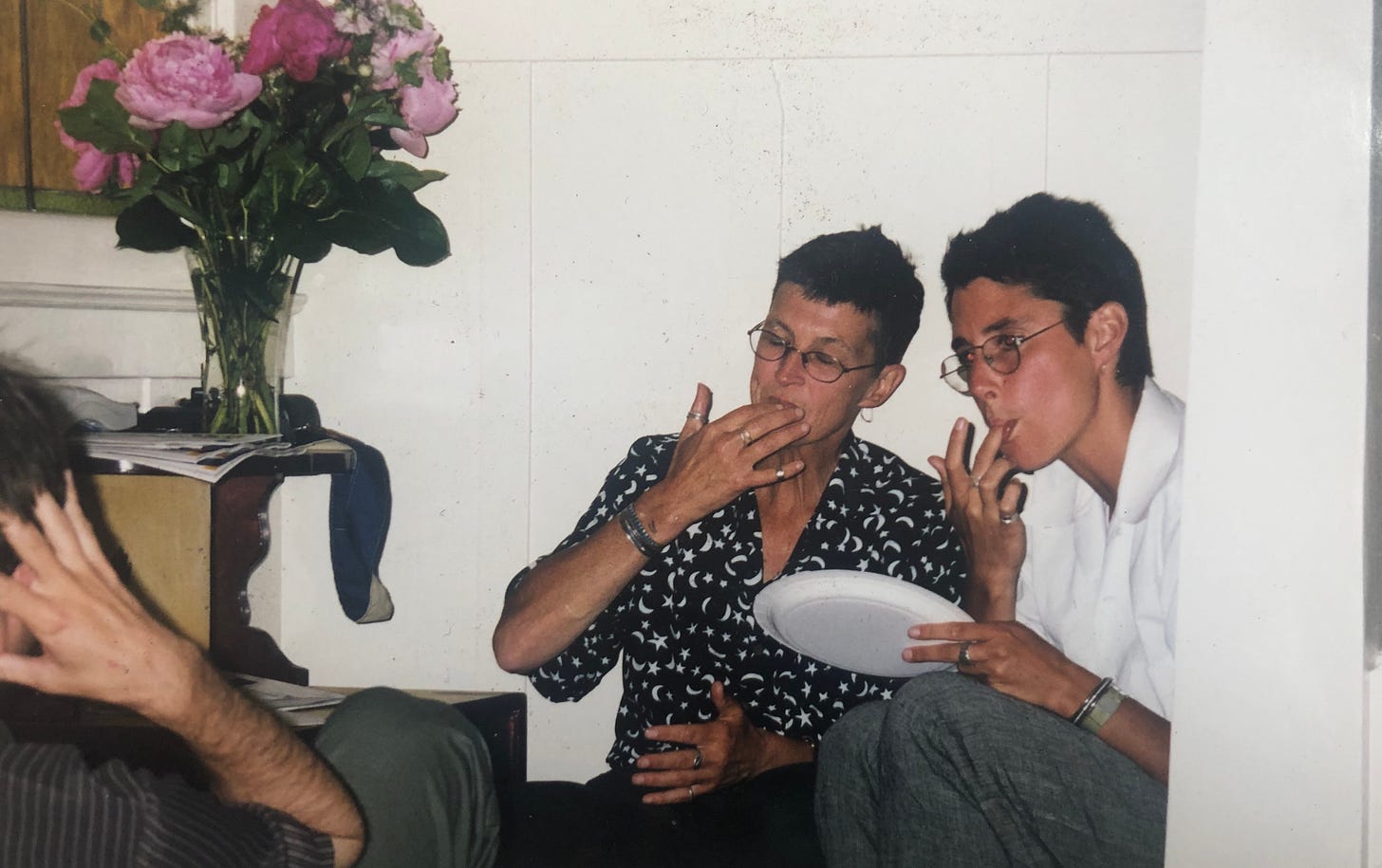

These lines remind me of my last visit with Christine, when she, Mercy, Chas (my husband) and I gathered at the memory care facility where Christine was living. Mercy had already told us that Christine had only a handful of words left. By this point, she and Christine had broken up. It happened before Christine’s diagnosis, and it was awful, first and foremost for the two of them, but for the four of us, too. Over so many years, we’d formed a great friendship that was no less a love-of-my-life because it criss-crossed two couples and didn’t last.

By the time of this last visit, Christine had made countless, difficult adjustments to a new kind of life, and she had formed new relationships in community with others. But one thing never changed. Her love for Mercy was steadfast to the very end. “Brown eyes,” Christine suddenly announced, as we were getting ready to say goodbye. She’d been mostly silent, and then — those two words. Words for Mercy. Words for I love you. Like Harper wrote, a fragment and a whole.

And of course you’re right that friendship is a special kind of relationship that asks and offers something specific in our lives as we keep becoming and becoming. There’s an incredible line from Wallace Stegner that I cite in the book. He describes friendship as “a relationship that has no formal shape … it is held together by neither law nor property nor blood, there is no glue in it but mutual liking. It is therefore rare.”

I am thinking about the glue that holds our friendships together even, maybe especially, when change inevitably comes.

How did you think about what you owed Christine, one of your friend’s in the book who has died, in writing this? I am also writing about my dad, who is very much alive but has dementia, and I’ve been wondering how to think about what I owe him.

One of Christine’s greatest fears was that she would be forgotten. She wanted to be remembered as a teacher, a writer, a friend, a truth-teller, a lover, a fighter for justice. I owed her a story where she appeared with all of her complex dimensions.

Christine’s writing changed over time as her dementia took hold. Her sentences became more syncopated, fragmentary, shot through with punctuation — rows of periods, exclamation points, question marks — and eventually, a mix of known and unrecognizable words. It pained her, for the written word, which had been so dear to her, such a powerful tool, to more and more escape her grasp. And yet, she never stopped writing. I owed it to Christine to meet her voice, on the page and in life, with an evolving appreciation for her lyricism, honesty, humor, and indefatigable will to express and connect.

Christine officiated my wedding. She told Chas and me that over the course of our relationship, there would be “times of wounding and the necessity for healing … In conversation,” she said, “there will be the unspoken.”

I owed it to Christine to dwell in her unspoken, to tune into meanings within, beyond, in the absence and aftermath of her words.

What are your favorite novels about friendship?

I already talked about Stegner’s lines on friendship from his novel Crossing to Safety, the story of two couples who meet when they’re young and form a relationship that carries them through the joys, hurts, and regrets of having children, chasing careers, experiencing illness, and nearing death. At one point, the two couples take an overseas trip, and Stegner describes their enthusiasm as insatiable. They can’t get enough of the city or one another. “I say me,” one of the characters says of how he was feeling, “but I think I mean us.”

That one line captures so much, for me, about friendship as a defining love of our lives, one that runs so deep and is so foundational that there is no disentangling the I from the we.

The other book I want to mention is Exit West by Mohsin Hamid. This isn’t, on the face of it, a book about friendship. It’s the story of two young people, Saeed and Nadia, in an unnamed country tipping into war, who migrate across a violent world through magical portals that appear here and there — a bedroom closet, the end of an alley — and allow people to escape where they are and emerge somewhere new.

In this sense, it’s a book about precarity and belonging in apocalyptic times. But there’s another way to read the book, through the exquisitely tender relationship between Saeed and Nadia. It begins with the two of them falling in love but really, most of the story traces — with enormous delicacy — their falling out of it.

They don’t fall into nothing, though. They emerge somewhere new, into something maybe even more enduring and true: friendship. Over time, they allow years, decades to pass without seeing each other. Finally, in the book’s last pages, they get together for coffee in the city where they’d met. Nadia asks if Saeed ever got to see the stars over the desert, as he had wanted to when they were young. He says that he had, and that one day he could take her to see them too, “and she shut her eyes and said she would like that very much, and they rose and embraced and parted and did not know, then, if that evening would ever come.”

This moment just destroys me — for all it says and doesn’t say, for all that Saeed and Nadia know and don’t know, for the way that friendship can be like this, a holding and a letting go.

Buy the book here. We have donated to Doctors Without Borders for Gaza relief in honor of Lissa’s labor.

Whose words come out of your mouth? What friends have you shared a language with? Share this post with them, and leave a comment. I can’t wait to hear how this strikes you.

I hope, Courtney, that at some point , even if it is ten or fifteen years from now, you might write a book circling in some way around the theme of living with your father- and with the rest of your family- in his decline but perhaps also reimagining what family support, institutional systems, might look like for this time of life together.

I hope you are saving artifacts of this journey.

At my age I am old enough to have lost many people. I absolutely hear their language and expressions in mine, see them in places that were meaningful for us, and think of what they would have thought about something.

I absolutely feel I am carrying others with me as I continue to move in the world.

I read Soep's book as part of a personal syllabus in exploring the idea of making art entangled with other's voices, especially those we love. I've also read Samantha Hunt's The Unwritten book, and different renga poems. And the book that was a topic of a recent newsletter here too, The Emergency Was Curiosity.

I loved that Bakhtin was a character! And I really appreciate the gloss the author gives here on the book and her intentions. It was a lovely portrait of these 2 people who meant so much to her. I am working with poems and notes left by my dad, whose sudden death in 2020 devastated me and our whole family. I hear his voice in my voice, and I hear both his and my grandfather's in the intonations of my aunt, his younger sister.

I love the honoring of the unsaid that she expresses here, as well. There's so much we will never know about others, even our own kin, because we project onto them and hear in their voices things that come from US, not them.

I would love to know more how the perspective and lives and friendships shared with these friends shaped the author's voice and life. Did the friend's husband who died connect with her in life in such a way as to shape how she writes now, like Christine did? Not just the fact of his death, but how he lived his life?

This book reminds me a bit of H is for Hawk as well, as a journey through grief, and an act of using literature or literary biography (TH White in the case of H is for Hawk, Bakhtin here), to think through the ungovernable experience of loss.