What was your first question?

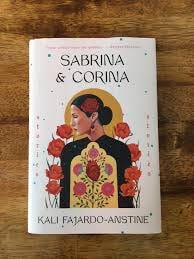

I just finished Sabrina & Corina, a collection of short stories by Kali Fajardo-Anstine, and it took my breath away.

It’s full of girl narrators, trying to make sense of the adult world, in all its beauty and hypocrisy. Fajardo-Anstine is from Colorado, and the book is full of sensuous references to that place, also my homestate, that made me so nostalgic. It also reminded me of a piece I published during my tenure as a columnist at On Being that I thought I would share again here, in case you missed it.

What Was Your First Question?

When Dorothy Day was a little girl, she witnessed the world around her reduced to rubble by an earthquake. It was 1906. Fifty thousand refugees fled from San Francisco by boat and were welcomed in various spots along the east bay by welcoming strangers, and were fed, clothed, and comforted. Day wrote of the formative experience:

“While the crisis lasted, people loved each other. It was as though they were united in Christian solidarity. It makes one think of how people could, if they would, care for each other in times of stress, unjudgingly in pity and love.”

In other words, at just eight years old, Day asked, Why can’t people always care for one another unconditionally? It’s a question she continued to ask in various forms for the rest of her life — cofounding the Catholic Worker Movement and its many Houses of Hospitality, and becoming a radical legend in the process.

Hearing about Day’s first, big question got me wondering about my own. What is the question that I asked as a little girl and have never stopped asking? How has asking that question defined, even if unconsciously, the choices I’ve made, the things I’ve created, the legacy I will leave behind?

I was stumped at first. Seeing the allegory embedded in one’s own life can be challenging, especially smack in the middle of it. But I started listening for other “first questions” — as I’ve come to think of them. Susan Cain showed up at camp with a suitcase full of books; as the other kids, and probably even a few counselors, gave her strange looks, she wondered: What’s wrong with being quiet? She would go on to write a bestselling book on society’s bias for extroversion called Quiet and launch a movement of sorts to encourage workplaces and schools to embrace those of us who get energy from solitude.

Oprah Winfrey has talked about the way in which multiple sexual assault experiences (starting when she was just 9 years old and none of them prosecuted) led her on a path to tirelessly unveil the light and dark of human experience; it’s as if she’s always asking, What’s the cathartic story here? Similarly, “our own” Krista Tippett has reflected that she wonders how much of her career was seeded in the fact that her father was adopted and rarely, if ever, spoke about it; she has spent a lifetime essentially asking, What shapes people? through kind, fearless conversation.

If my own family is an interesting study: My father grew up answering the door for debt collectors and became a bankruptcy lawyer; one could think of his “first question” as How can I stay safe? My mother was born a wild spirit with a mother obsessed with appropriateness; she jaywalks with a sly smile on her face and loves to point out the elephant in the room because so much of her life has been guided by the question Why not?

Many of these first questions are asked from a painful place. So many of us didn’t get what we needed as children and we spend a lifetime looking for it. But the upside of that initial emptiness is that we create dynamic and beautiful things out of our yearning.

In some ways, these questions are so powerful because they are asked from such a pure place. Children are famously intuitive about underlying dynamics that adults assume they couldn’t possibly understand. They focus in on unspoken truths like homing pigeons and then have the audacity to speak them; the world hasn’t yet acculturated them to fearing the sound of a silence breaking. They are not, in the best of all possible ways, team players. They are inexhaustible witnesses and truth seekers.

Which is what we all are, underneath the home training and the wear and tear of decades of living on this brutal planet. Peel back the layers and we are still the little people we once were, looking around at the adults and wondering what the heck is going on. We are curious and outraged and perhaps sometimes naively sure that there is a better way.

Which brings me to my own first question: I believe it’s less about my family of origin and more about my demographic of origin. I spent so much time in my seemingly perfect neighborhood of white, middle-class people — doctors and lawyers and homemaker mothers — wondering why no one seemed to publicly acknowledge the pain underneath. The bitter divorces, the eating disorders, the rape, the unacknowledged pregnancies, the mental illness… what mythologist and storyteller Michael Meade calls “the white fog.”

Like so many suburban kids, I gravitated towards blues, jazz, and hip-hop music, where people were honest about pain (of a very different kind) and started to ask inconvenient questions within my own family. I discovered that my paternal grandmother had struggled with undiagnosed and mistreated bipolar disorder and a trunk of unlived dreams. I think that, too, is running through my blood in some way (epigenetics helps confirm that hunch), even though I only met her a handful of times before she died.

Which, in some strange ways, leads in a very straight line to a lot of the writing I do. I seem perpetually interested in how to strip privileged people of our delusions — whether it’s a generation of young women who have turned their bodies into infinitely improvable projects (the subject of my first book, Perfect Girls, Starving Daughters), or whether it’s a country that I believe clings to an outdated idea of what the American Dream is to our own peril (the subject of my most recent book, The New Better Off). I am always asking, in a sense, How can we wake up from our delusions of perfection? (Perfect body, perfect woman, perfect family, perfect home, perfect country…)

That question surprises me a bit. It’s not what I consciously craft my life or work around. I wouldn’t put it on the top of a strategic plan or claim it as my mission statement. And yet there it is, a sort of internal logic to the way I spend my energy and the things that really light me up — both professionally and personally.

So what was your “first question”? What is that question you weren’t allowed to ask as a kid, so you’ve asked it every day since? How has it influenced, even if unconsciously, how you’ve navigated through the world?