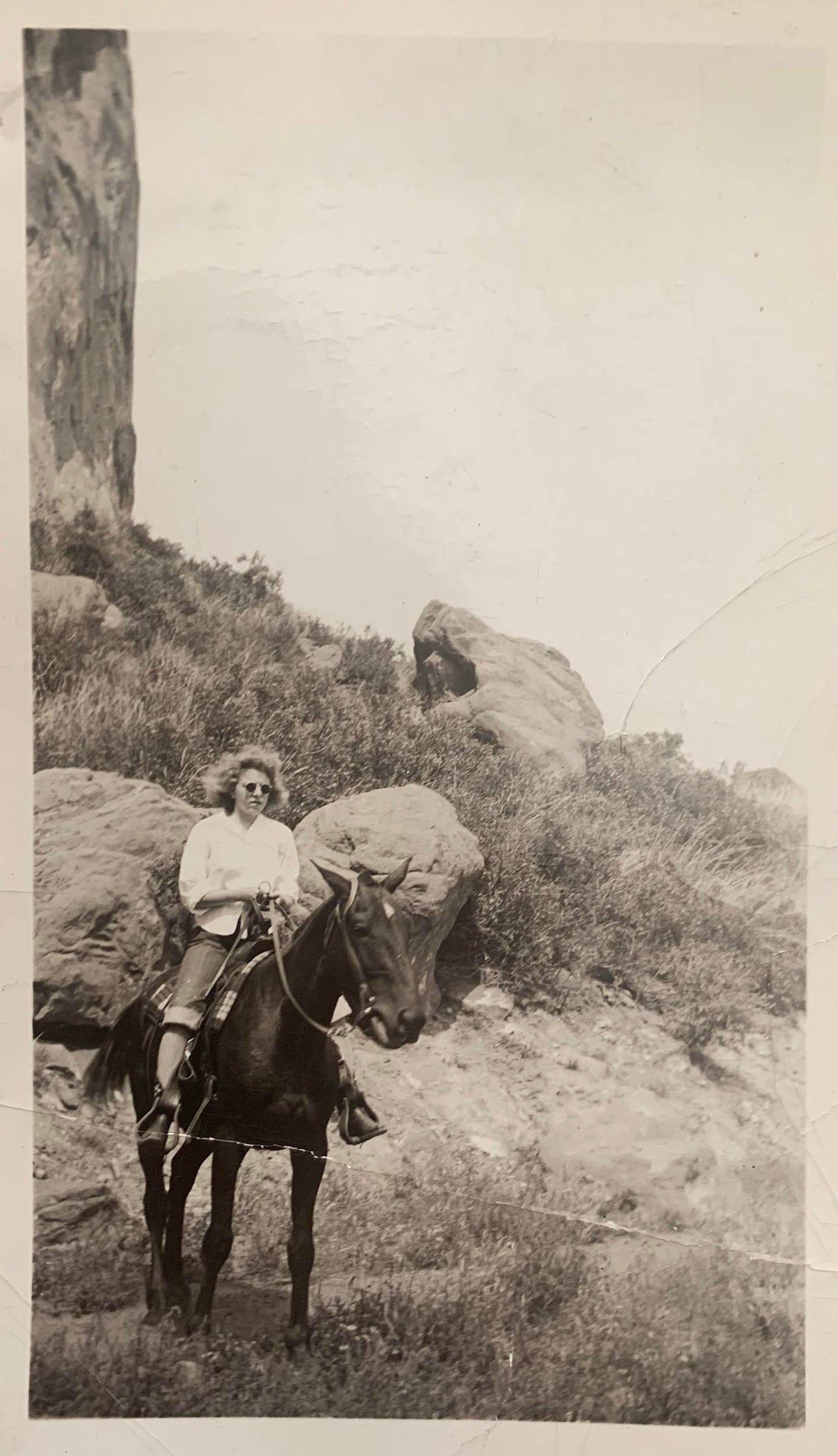

I’ve been working on an audio story about my long dead grandmother for the past few weeks, which means I’ve carried her around with me more than usual. We sit at stop lights together and I feel a sadness welling up in me. What happened in your family of origin that left everyone so fragile? We go on hikes, surrounded by eucalyptus trees, and I can feel how much she loved the Bay Area. I know, doesn’t it smell gorgeous? I think to her. She lived here for a short time, likely at her happiest. She was an editor. But then things fell apart again. She fell apart again.

Forty years later, I somehow feel responsible for piecing her back together. It’s as if my own journey won’t be whole until I make sense of hers.

I tell my big brother, still one of my best friends on this broken earth, that I’ve been working on a story about her again. My work on her never seems done, like a narrative that just won’t rest. Usually when I write something, it leaves my system--like an exorcism. Not with her. She never seems to go away.

My brother tells me about an idea he learned from scholar and somatics practitioner Sean Saifa Wall that we can heal backwards--that our own ability to understand our ancestors’ pain and heal the legacy of it in our own lives actually soothes them in some ineffable realm. It’s a motivating idea for a helper like me. This isn’t just solipsism; it’s generational repair.

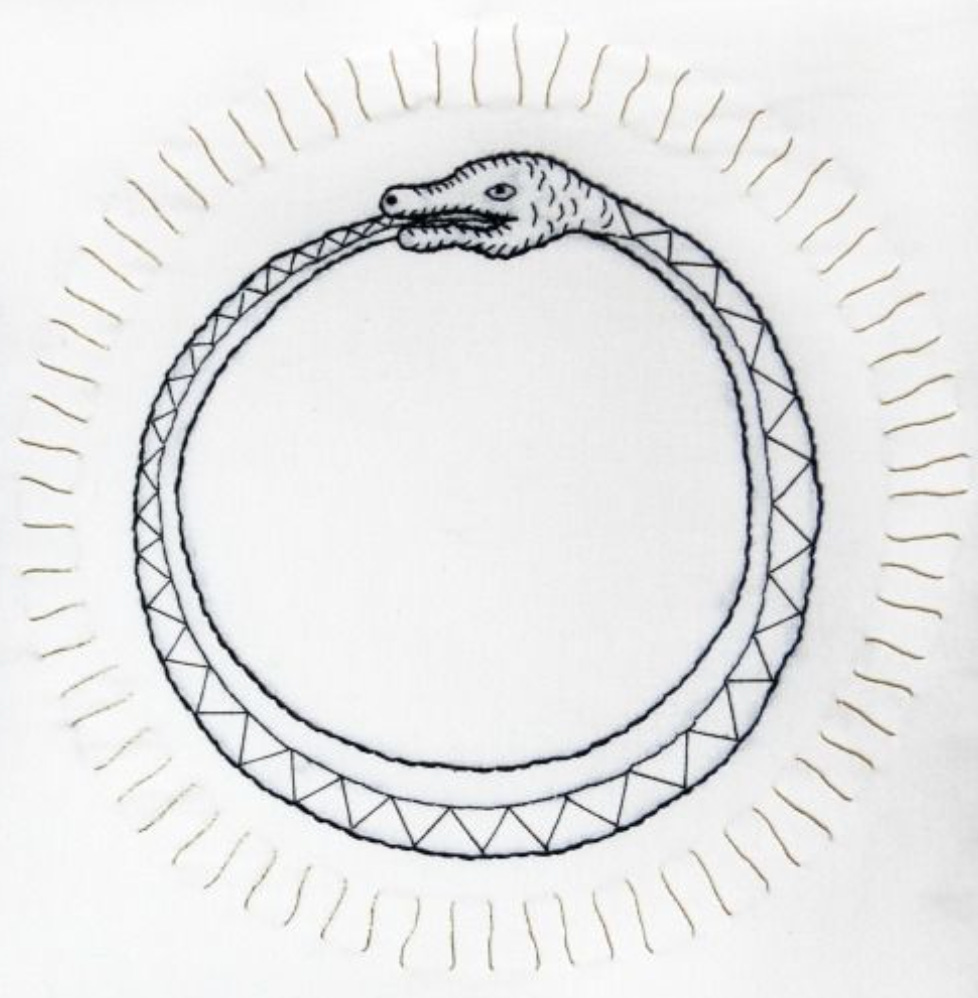

Generational repair is everywhere right now. We’ve been calling this portal that George Floyd’s murder opened reckoning, but I’m not sure it’s a word with enough temporal dimension to fit around what we’re feeling. It’s like the past has finally caught up with America, especially White America. Or has it circled back on itself somehow--like the ouroboros serpent eating its own tail?

I can remember a time in my teens and twenties when I actually longed for a more palpable sense of history. It felt like all the important things had already happened. I was jealous of my parents’ protests and fashion, of my grandparents’ victory gardens and WPA art. It felt like we were a generation with nothing to push against, nothing grand and dramatic by which to define ourselves.

If this is what that feels like, I can understand why I craved it, and I also finally understand how destabalizing it is, how much it asks of you. It’s like the task before us--to finally confront our past--requires spiritual muscles most of us have never developed. I’m not sure many of us actually believe that generational repair is possible.

And why should we? We so rarely do it in our own families. We turn our triumphs into allegory, and we bury the pain and violence in the back of our closets, hoping to spare the next generation from the darker side of finding yourself born into a human family. But just as thermodynamics teaches us that energy cannot be destroyed, so our lineage of pain cannot be disappeared. It lives on in our patterns, our questions, even in our DNA. Our cells are literally altered by the unspoken stuff.

As it is with our families, it is with the nation. We’ve been trying to speak the pain and violence back into our consciousness these last couple of years. Many of our journalists and poets and artists are doing a brave, beautiful job of it--my God. I got to hear Nikole Hannah Jones, creator of The 1619 Project, and filmmaker Barry Jenkins in conversation last night and they spoke so much about their creative work in the world as a debt to their ancestors, a way of unearthing and complicating and legitimizing their stories, of honoring their brilliant survival, of centering them in American history. They are doing this while looking backward, eyes wide and unveiled, describing what they see. The description is resurrection. The goal is honoring, but also action. How do these new ways of seeing work on us? What do they compel us to do now?

Many of us are listening. Pausing. Looking back. Looking inside of ourselves. Craving to repair in some meaningful way as we move forward.

But “unwinding history,” as George Gascón, a district attorney trying to decarcerate an entire county puts it, is no simple thing. It is not a thing without fury and confusion. It is not a thing without loss. It requires sitting with feelings that, quite possibly, no one in your family has sat with for decades, maybe even generations. It requires revising, renaming, redistributing. It requires personalizing things which you didn’t think were yours and depersonalizing things which you were sure were. It requires humility and chutzpah.

This is why somehow I understand that carrying my grandmother with me, being patient with the way her story works on me and through me, is a way of building spiritual muscles that this moment demands. How do you face generational pain? How do you make century-deep meaning? How do you live differently--either to break a pattern in your own family or a pattern in your own nation?

I don’t know. But I think it’s going to require walking forward and backward, being exquisitely still with the depth of our sadness, being brave, being kind, letting go, holding on. No one is really dead as long as we still have our earthly sense to make of them, as long as we have our healing to do.

Thanks to Meditative Story, particularly my buddy and brilliant editor Chris Colin, for the chance to work on a piece about my grandmother. May it inspire you to acknowledge even the painful truths of your family and heal backwards. Would love to hear about it.

Wonderful piece, Courtney. I love the concept of healing backwards. It's really got me thinking. I'm going to reflect on this and will mention you in my newsletter if I write a piece about it. Thank you for helping me reflect, respect and accept.

I recall Courtney expressing admiration for her grandmother years ago so I’m happy that the effort and inspiration remains in force today . This also reminds me of the brilliant book by another outstanding Barnard alum, Fatima Bhutto, who published a remarkable biography of her beloved father. Such memories of family heritage by eloquent writers like Courtney and Fatima are treasures for us all. Thank you! Peace, DD