There’s another episode of The Wise Unknown out y’all - this time with Samin Nosrat and Twilight Greenaway. Take a listen and tell us what you think!

And as always, if you appreciate reading these Q&As, please consider supporting with a paid subscription. For each interview I do, I donate $250 to a nonprofit organization of the person’s choice out of our collective subscription fees, so you’re not only making my work possible, but all kinds of amazing work all over the world.

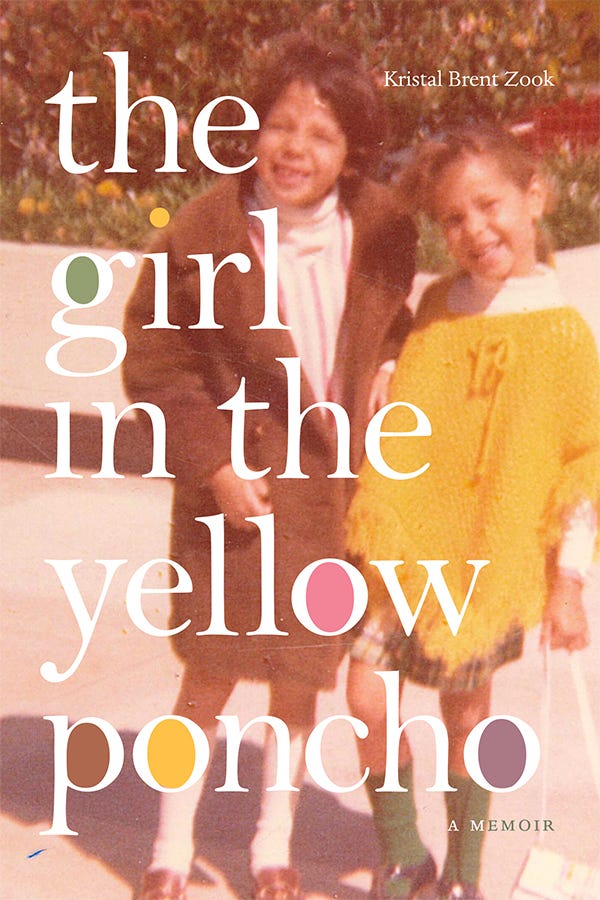

Too often our narratives around race are black and white, told as if America has been on solely a binary journey, rather than the more accurate picture of so much intertwining, mixing, blending, forgetting, and remembering. In journalist Kristal Brent Zook’s new memoir, The Girl in the Yellow Poncho she tells one seeker’s version of the non-binary racialized life—a girl, who becomes a woman, who never stops trying to understand the implications of her roots and her wings. I know Kristal from my New York days (we used to do a traveling panel together on intergenerational, intersectional feminism!) and so it was a joy to be reacquainted with the parts of her amazing story that I already knew, and learn so many new things about who she has become and how she got there.

Meet Kristal…

Courtney Martin: Why did you decide to write this memoir now? It's such a sweeping story of your life, but I know you have a lot of life left to live, too.

Kristal Brent Zook: I started thinking about this generation of multiracial youth when my daughter was born. She’s of African American, Anglo, and Southeast Asian heritage and I wondered how her social formation and sense of identity would be different from my own. Originally, this was going to be a journalistic book—looking at the shifting demographics and politics of mixed-race identity. We had a proposal and a potential publisher. But to my surprise, a more personal narrative began to take root. At some point, it became a book about my decision to look for my father (again), and to finally heal the generational trauma that existed within myself and my family.

I love how much you wrote about your dreams in the book. What advice would you give to those who haven't mined their dreams for insights previously but are curious about it?

Dreams have always been such a central part of my evolution. I can’t overstate their importance. As a journalist, I was obsessed—interviewing the UCLA scientists who were studying dolphins (the only mammals who don’t dream apparently), and quantum physicists, and neurobiologists. I wrote several articles on the science of dreaming and the mysteries of the unconscious. Although so much remains unexplained about the dream state, we do know that dreaming matters profoundly, and that it’s crucial for our sanity, our creativity, and even our survival. I would tell those who are interested to start by keeping a notebook by the bed with the intention of simply paying attention. In my case, I found that the more conscious attention I paid to my dreams, the faster and more furiously they came. It was as though the dream messages—or my own unconscious knowing—were just waiting for my conscious brain to finally take notice and listen.

A lot of the book traces your own racial formation -- being raised by Black women, and also wrestling with your own identity as a biracial woman and someone with a lighter complexion compared to others in some of the radical Black womanist and feminist spaces you gravitated towards. What gives you hope about the public discourse these days when it comes to biracial identity in America? What continues to frustrate you?

What’s changed is that there are much larger numbers of multiracial youth today in K-12 especially and in universities and workplaces, far more than there were when I was growing up. The country has seen a 278% increase in the multiracial population over the last decade. It’s exciting to me that young people today feel empowered to claim their entire selves, choosing labels like “Blackipino” and “Blasian” to describe themselves. Although I must admit, I was one of those who snickered a bit when Tiger Woods first called himself “Cablinasian” way back in 1997. In truth, he was ahead of the curve. What’s disappointing and somewhat surprising is that many of the same struggles that have always existed, still exist, in terms of interracial dynamics, colorism, and feelings of exclusion and not belonging. Also, parents often don’t educate themselves enough about the unique ethnic, cultural, and political heritage of their multiracial children, even today. Many still don’t know how to have the kind of conversations that would help them navigate the world inside mixed-race body. I’ve written and reported about some of these ongoing challenges among families, at universities, and among the broader culture on my Medium blog.

The book is so much about healing --yourself, your relationships-- and that healing comes in waves and over decades. It feels like we live in a quick-fix culture, where everyone wants 7 steps to self-care. What has writing this narrative of repair and return taught you about how long healing can take?

Absolutely, what a great question. At some point after the book was published, I had a sudden revelation. It dawned on me that there was still a part of my healing journey that needed care and attention—a piece that I had kind of forgotten about. At first, the thought floored me. There’s more? I thought to myself, exasperated. But there’s always more if we’re alive. We’re complicated, evolving human beings. The idea that one could ever simply be “done” becoming their best and most powerful self is ridiculous. I describe myself in the book as a perfectionist, but there’s another, healthier way to describe that personality trait, too. I also see myself as a striver, a dreamer, a hoper, and a relentless optimist. Hence, the yellow poncho.

I fell madly in love with your grandmother, Dra. What do you think she would think about this book? Do you still talk to her in your head?

Oh, this question makes my heart smile. Thank you. My grandmother was my tireless champion. In her later years, she continued to live alone in a one-bedroom apartment that was part of a senior living complex. It would have been hard for me to imagine any other lifestyle for her that wasn’t independent living. She had her own kitchen, but there was also a shared, communal dining room, and she would walk downstairs every day to have lunch and dinner with her friends. For years, whenever I published an article—in Essence, or anywhere else—she wore her neighbors out by carting any and all of the magazines down to the lunchroom so that everyone could see and appreciate her granddaughter’s latest work. She would love the book because it was about all the ways she defended and upheld her family, and because it was written with so much love, for both her and my mother. Janet Mendel, my grandmother’s longtime employer and friend, brought tears to my eyes recently when she noted in an email that Dra was surely, at this moment, giving out copies of The Girl in the Yellow Poncho to everyone she comes across in heaven.

Buy the book here. We will be donating to Futures Without Violence in honor of Kristal’s labor.

I have realized with awe only in this late decade of my life how long it sometimes takes to work through something, plus the challenge of learning how to juggle that work with the rest of life, as none of the rest of these things stop!

What a beautiful interview, Courtney! I look forward to reading the memoir. I, too, have always had an interesting dream life. I don't write them down, however, but I do have a notebook where I write down any insights that come to me in meditation. They sre only of interest to me, but I find them often amazing, and if I don't write them down, I forget them right away. Thank you for writing this!