The unbearable lightness of biography

on telling the stories of those we love and how flawed it all is

Hey friends, have I mentioned lately how grateful I am for your support? Thank you for subscribing. Thank you for becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you for sharing these little dispatches with those you love. Thank you for giving gift subscriptions. It all means the world to me as I keep riding the waves of creativity, caregiving, and estimated taxes.

My dad is not drinking his coffee, which is strange because when we’re at home, he not only drinks his own beverages, but all of mine, too. He’s nervous, I’m thinking. He can’t articulate that; the connection between the feeling of nervousness and the word nervous has been severed in his brain as far as I can tell (along with so many other significant erasures and erosion). We’re at his first morning of a 3-day assessment for a day program for people with Alzheimer’s and dementia.

One of the staff members kindly asks, “What did you do for work, Ron?”

My dad looks at her blankly, knowing a response is expected but coming up with nothing. “He was a lawyer,” I answer.

A man sitting at another table turns and shouts, “I was a lawyer, too! For six years! Then I became a preacher!” He is exuberant and seems to have words in all the right files in his brain; I’m a little jealous of his functionality on behalf of my dad. “How long did you practice law?” he asks my dad.

Again, my dad understands he’s supposed to provide a response, but has none to give. His dementia is like this, at least for now—the rhythm of social interaction is still crystal clear to him but he can’t play any of the notes. “Forty years,” I say.

“Is that right?” he says, wide-eyed. It’s his catch phrase, now but also in the past. He was known among all my friends as the dad who actually listened when you talked and said, “Is that right?” incredulously at regular intervals.

A small woman in a bucket hat sitting across from us says, “I was a lawyer,” but I can tell somehow that this is not true. She is also invested in the rhythm, but has no investment in the veracity of the notes. She’s got a blank crossword in front of her and an agreeable smile.

We had a lot of conversations during the three days that my dad was “assessed,” but many of them started with a big-hearted professional asking us what my dad once did for a living. I found it strange, even as I totally get why. My dad retired a very long time ago, so perhaps that’s part of why I feel estranged from that part of his biography, but I also feel like it’s one of the least foundational things one has to know in order to really understand him. He could have been an electrician or a teacher or a nurse in a dementia day program for that matter.

He was a bankruptcy lawyer because his parents were constantly going bankrupt when he was a kid and he hated it and this was a way to grasp for some security. He was also raised Catholic and hated that, so became Buddhist. He also had an erratic, deceitful father and hated it and so went to lots of therapy and became a great dad. So much of his biography, when you lay out the facts, is a tale of reaction.

So here we are—his family—tasked with being the stewards of his story to these caretakers at this day program, and I’m struck at just what a heavy weight it feels to me. Heavy like meaningful and heavy like impossible. Importantly, they don’t seem to be asking what he did for a living in order to decide he’s “important” or “smart” or worthy of care. This is blessedly the kind of place where no matter what our answer had been, I know that they would have given him the same level of care. But they want insights into what engages him, lights him up, defines him, so they can surround him with reminders of his own vitality. I’m deeply moved by this. When they tell me that they started yoga class on Tuesday with a group sing-along of “Here Comes the Sun,” I quietly cry.

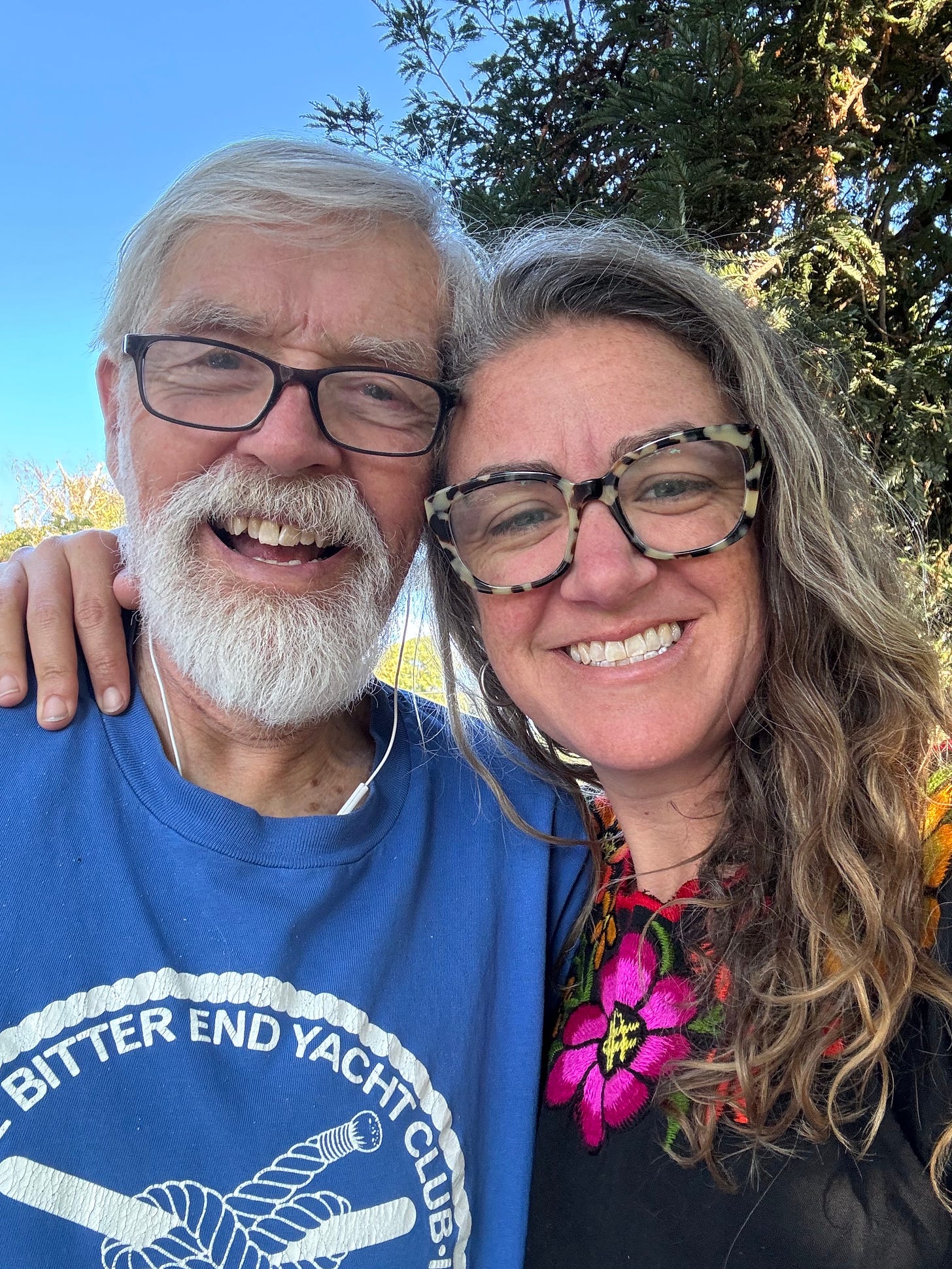

But I’m also thrashing inside of my own head about the incompleteness of everything coming out of my mouth and the mouths of my mom and brother who attend various meetings with me. My mom describes the international travel he used to love. My brother paints a picture of his mentally ill mother and how that shaped him. We tell them about the chronic migraines he used to suffer but no longer does. We tell them about him now, too: Beatles, ice cream, an encyclopedic memory for vintage cars, a lingering sarcasm and deep desire to make others laugh. What we are really telling them, over and over again in as many ways as we can think to is: he is beloved.

I remember when I was tasked with naming my daughters, I was shocked at how weighty I found the task. Of course I’d been naming things my whole life—my stray cats and weird Barbies and failed all-girl rap groups. But when the time came to actually name another human being, I found it unbearably big. How should I know what this little snorting, sucking creature would like to be named? I had just met her. What I thought would be a real delight, felt more like a power trip I didn’t want to be on.

The same feeling struck me at the day program, telling the physical therapist that my dad loves to dance and the Life Enrichment Director that he once resigned from the all-male business club in town because he said he couldn’t belong to a place that his son could one day join, but his daughter would be barred from. I feel so acutely in these moments that our naming of our loved ones is always an incomplete and biased project. I see my dad through my own filter and then present it to the world as whole, when really it is inherently inadequate—full of the holes of my own limitations. My story of my dad is my story of my dad and me. Always. Even when I’m not an explicit character, I am always the narrator now, cherry picking the details that are meaningful to me rather than the things that actually matter to him. I don’t know what matters to him about his past anymore. I don’t know what he would want these tough love nurses and exuberant new friends to know about what defined and defines him.

Should I tell them that he is left-handed? And used to draw Dennis the Menace characters? Should I tell them that he was an underwhelming athlete, but a great bowler? Or was once on a committee with Elizabeth Warren? Should I tell them that he used to swing in the backyard smoking his pipe after work sometimes? That he used to talk me down from anxiety attacks? That he doesn’t know how to cook a damn thing and never did, except for omelettes? Should I tell them about his messed up toe or his knock knees? Should I tell them about the time he shaved his beard and mustache off and scared me half to death as a little girl?

And, of course, wondering about the incompleteness and resisting the power of my task, I start to think about my own story. Who will tell it? What will they leave out? Will I even care?

After a wonderful family dinner made by my ever gracious sister-in-law, I was sitting on the couch with my dad, holding his hand, and I just started giving him sort of a state-of-the-union. “You’ve got two kids and four grandkids,” I tell him.

“Wow, is that right?”

“Yup, and I’m your daughter and I’m 44 years old now.”

“No way! For real?”

“For real, and you’re 76 years old. And you and mom have been married for 55 years.”

“Wow, really?!”

“It’s true. Can’t you believe it?”

“No, it’s amazing.”

“It is.”

“You’re really great,” he says to me, squeezing my hand.

“Thanks Dad,” I say.

“You really are. You’re a neat person,” he says. And I guess that’s his continued incomplete narration of me. And I’ll take it.

The word "beloved" always brings this poem by Raymond Carver to mind. It reminds me of all I have ever wanted and really all I ever want. Perhaps this is true for your Dad ... and you. Big Love.

Late Fragment

Raymond Carver

And did you get what

you wanted from this life even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

I just want to echo your Dad, Courtney: “You’re really great. You really are. You’re a neat person." Don't know where these tears are coming from... Love, Parker