Sometimes we talk about economics as if they were inevitable, as if the ways in which our lives are shaped by money are totally out of human control—like a weather pattern or a disease process. In fact, humans shape economies, and we shape them with our values—both implicit and explicit.

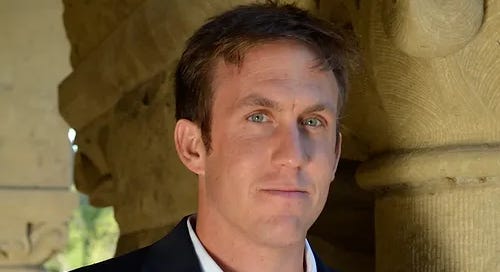

That’s why I really enjoyed reading New Yorker journalist and UC Berkeley professor Nick Romeo’s new book, The Alternative: How to Build a Just Economy. Nick is more interested in interrogating our biases and painting a picture of potential than he is playing political football, which I found so refreshing. I interviewed him for the City Arts & Lectures series (podcast forthcoming) and wanted to make sure to bring his ideas to the Examined Family community, so here you go…

Courtney Martin: How have we been teaching economics in the last couple of decades, and what's been missing? What does this tell us about the kinds of frames we most typically see in media coverage of economic issues?

Nick Romeo: I could give a very long answer to that question – it was hard in the book just to condense it to a single chapter. So to simplify outrageously, we've been teaching a lot of unempirical pro-market dogmas: specifically, the idea that unregulated or minimally regulated markets are typically the most efficient and thus the optimal mechanisms for allocating resources in all sorts of human areas, from healthcare to education to labor markets to food and technology provision.

There's also a general idea that both humans and companies are naturally rational and pursue unlimited growth as a straightforward consequence of this rationality. To the extent that we are irrational, nudges and hacks from behavioral economics are presented as revelatory tools for securing socially desirable outcomes. There's lots of excellent research, much of it done by economists themselves, showing how misleading and inaccurate these assumptions are, and economics textbooks are slowly changing to become more nuanced and more forthcoming about the political nature of many of the assumptions behind their models.

The media, unfortunately, has not been particularly quick to absorb this more empirical and intellectually defensible vision of economics. There's often a really misguided deference to supposed experts who cite a statistic, whether about economic growth or interest rates or unemployment, and then act as if an incredibly narrow set of policy responses to this statistic is the only conceivable option. Journalists are supposed to ask difficult questions and interrogate lazy assumptions, but often their jobs and their funding depends on not rocking the boat too much. Journalists, too, to the extent that they have been indoctrinated by economic education or just American society have often absorbed some of the same attitudes and dogmas that make it hard for them to recognize just how misleading their coverage is.

The solutions you look at in this book--true pricing, worker cooperatives, job guarantees--require collective, not just individual action. What does a family that wants to align their economic lives more with their moral values do to be a part of these solutions?

This is a tricky issue. On the one hand, overstating the role of individual consumer choice risks just reinforcing the wrong paradigm, by suggesting we don't actually need better laws, policies and regulations. So it's true that we can't just virtuously consume and purchase our way out of these various crises, one Fairtrade avocado at a time.

On the other hand, most individuals are not moving the levers of policy or allocating huge pools of institutional capital, so their options are limited. So what can normal people do except try to buy ethical products and vote for decent candidates, however inadequate this feels and however limited the availability of such products and candidates really is?

I don't have a super satisfying answer here. Doing small things is better than doing nothing. Fairtrade does do some good work. More broadly, collectives are ultimately composed of individuals, and small to midsize collectives can be really impactful. City governments are often more responsive to citizen pressure for initiatives like participatory budgeting or climate budgeting or using procurement to support real living wage businesses or worker owned businesses or even trialling a public option for irregular workers. Initiatives launched first at municipal levels do sometimes shape state and eventually federal actions.

For people and families that have investment funds and retirement accounts, it’s also good to ask the people who manage that money for you to provide really substantive options. So-called ESG investment is rightly mocked, because it usually is meaningless. It doesn't follow from this, however, that we should just invest our money in the same old companies and not worry about it. I think asking people who manage money for a living to create portfolios where you can actually have visibility into how workers are paid and treated, whether they're given equity and ownership in their companies, what those companies' carbon footprints are, this would be an incredibly helpful development and even individual small-scale investors can press for this.

What was your biggest surprise while reporting?

That economics could be interesting. I'd always found the subject, both in academic and popular manifestations, kind of tedious and technocratic. For me the key recognition was that economics is actually a branch of political philosophy, and if you push hard on supposedly economic questions, they tend to bottom out in really rich and interesting philosophical ones: what is a good life, what is a just society, what defines rationality or happiness, et cetera.

If you could pick any one place that your reporting took you and spend a year there, soaking up the benefits of a more moral economy, which one would you choose and why?

The Basque country of northern Spain, home to the Mondragon cooperatives. Not only is it an extraordinarily beautiful landscape, the culture and history are also fascinating. Being there, you really feel all of these intangible cultural and psychological benefits that flow from a more humane and reasonable economic system. The density of civic associations and communal life is pretty astonishing from a hyper atomized American perspective.

You are quite a literary guy. What novel do you think taught you the most about how to be a shrewd and original economic thinker?

What a great question. Excellent novelists can register the subtleties of how psychology, institutions and society function that are often missed by the schematic models of neoclassical economics. The Neapolitan quartet by the Italian novelist Elena Ferrante comes to mind. She writes about poverty in a way that is not sentimental or preachy, yet she makes its power to deform and limit human lives so piercingly clear. The 19th century French novelist Balzac is also exceptionally perceptive about class and economics. I love a sentence from his novel Pere Goriot:

“The secret of a great fortune made without apparent cause is soon forgotten, if the crime is committed in a respectable way.”

Just changing the curriculum of business schools and economics departments to mandate intensive reading of great novels would go a long way towards improving some of the pathologies of those fields.

Buy Nick’s wonderful book here.

One of my resolutions for 2024 is to research alternative economic models. I've added Nick's book to my stack of materials, which also includes Humanity @ Work&Life: Global Diffusion of the Mondragon Cooperative Ecosystem Experience. Wanting to see what transformations we can encourage here in Oakland and the Bay Area...to serve as an inspiration for state and national policy. Thanks for introducing us to Nick's work, here and in your Sunday 5 - his ideas and framings are fresh and much needed. 🙏

That idea that humans and institutions are inherently rational has always felt bonkers to me!