One of the many deeply mysterious things about loving someone with fairly advanced dementia is this: the majority of people I talk to seem to have shockingly limited insight into what it is like. I don’t mean that it exists. I don’t mean that they have a great uncle with it. I mean the real, daily texture of it. And it’s a disease that almost 6 million people in the United States have right this very minute. The math doesn’t add up. How could this be?

Maybe this experience is a result of my age? I’m only 44 years-old, meaning my dad’s cognitive decline started rather young. (My parents shared the official diagnosis 7 years ago). I have a uniquely intergenerational group of friends, but the majority of my friends are around my age. Maybe I’m just ahead of the curve on taking care of my aging parents? I’m one of those people, like so many in the “sandwich generation,” who gave birth right as my dad started to decline. Watching your kids become themselves while your parent un-becomes himself is a hell of a thing.

Maybe this experience is a result of institutionalization? Of the 6 million people in the U.S. with dementia or related diseases right now, many of them are in memory care facilities. When I do have a friend who is familiar with what it’s like to love someone with cognitive decline, they tend to be a grandchild—all grown up—reflecting on what it was like to visit their grandparents in an institution of some kind. Of course this is a formative experience, but it’s quite different from what my own kids—for example—are experiencing on a daily basis.

Stella—my 8-year-old—is learning to weather her grandfather’s inability to distinguish between her own icee and his. Maya—my 10-year-old—knows that bringing her grandfather a mint when he’s feeling agitated can help redirect his attention. Both of them are learning to share their mom’s attention in new and sometimes frustrating ways. I’m not visiting my dad on a weekly or even daily basis; I’m bringing him little bowls of fruit in the morning as he sits next to my mom and watches quirky TikTok videos, reading Pema Chodron to him aloud, making sure he doesn’t wander our new neighborhood. My husband is taking him along on errands so my mom, brother, and I can talk about the care plan for the week ahead—when the doctor’s appointments are and how we can get my dad’s knee checked out, what a new early morning routine might be so my mom can get more sleep, and where the power of attorney can be found when needed. This is not a Sunday afternoon visit with banana bread; this is a 7-days-a-week enmeshment with all of the beauty and crush that entails.

But I have a hunch that it is about something even bigger than my age or the way in which (for now) we are handling my dad’s care; I think it has to do with our public imagination. It’s not that there aren’t other families navigating the same wild waves we are as we live with and care for my dad. It’s that what these families are living through isn’t a living, breathing part of the public imagination.

Case in point: when you read the word tantrum, my guess is you immediately have a vivid picture of a kid losing their shit in a grocery store aisle, right? What about when you read the word sundowning? For some of you, that might conjure up a vivid picture of something you’ve weathered or hear stories from a friend about, but can you name a movie, book, or other touchstone of our culture that depicts it? Me neither.

Sundowning, for those who don’t know, is a very common experience for people with dementia or related diseases where—come happy hour—they will turn decidedly unhappy, convinced they are supposed to be somewhere else. For my dad, it’s like an unquenchable thirst—he feels an undeniable sense that we need to get going, but the destination is unclear. He grows frustrated with the rest of us for not understanding the urgency, or responding to it. Even if we take him on a drive or a walk, shortly after we return, his nervous system is back on its old track—frustrated, agitated, and antsy.

Sadly this often strikes our sweet dad on Wednesday nights, when we have our family dinners that my sister-in-law lovingly prepares. We are all so happy to be sitting around a table together, reminiscing over a glass of wine. Last week I made a Balderdash game out of my mom’s internet passwords, with her consent, I swear, and we all laughed until we cried (you guess - is bearscat13 or wildwoman48 one of her actual passwords?).* We need these outlets right now. We need these shared meals and nourishment. We need these laughs and tears.

So why does everyone know what a tantrum is and so few know what sundowning is? Both are hard things. Both are weathered by a massive amount of families. But one is associated—even tangentially—with death, and we do not want to look at death, one of the two most universal experiences of life on earth. And we really don’t want to look at death that is preceded by decline, vulnerability, bodies and brains slowly breaking down over months and years. That is a visual and emotional oeuvre we’ll avoid like the plague.

And it is a plague. It’s everywhere. It’s painful as hell. And inside of the pain is something else—a pearl of great price.

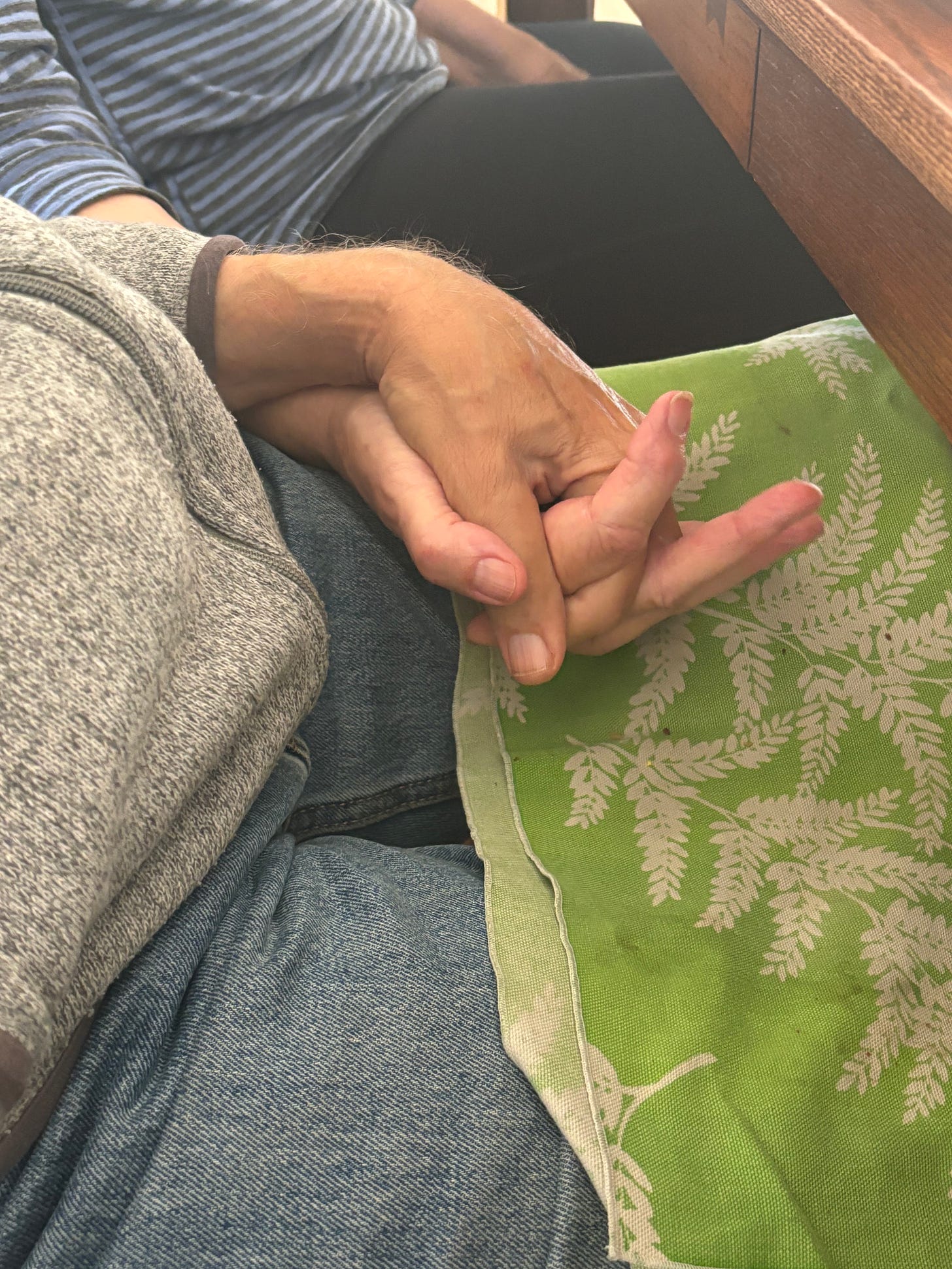

We haven’t learned how to quench my dad’s unquenchable thirst. We have learned to live alongside it together. My mom sits right next to him and holds his hand strongly—the physicality doesn’t solve it, but it helps a lot. They’ve been holding hands for about 60 years now—a deep groove that transcends language. My brother has learned that there is a particular loop that makes our dad feel a little more in control—either he or I will get in the car with my dad (which he calls “106,” referencing the last three numbers on the license plate) and start driving. We put on some Beatles and let our dad tell us which turns to take. This agency is part of the catharsis—you can actually feel his body relax with each new direction. We end up right back where we started about 10 minutes later, get out of the car, marvel at the darkness of the sky and the brightness of the moon.

Five minutes later, he might ask us when we are going to get going once again. The drive is not the cure, you see. The drive is the enduring. The enduring is the collective experience. The collective experience is the deep well of love that started when my brother and I no doubt had tantrums in the grocery store aisle and our dad held our bodies til the earthquake passed.

These—the drives, the pain, the pearl—are what I want to see more vividly and frequently depicted as part of our public imagination. We need that accompaniment, that preparation, that catharsis — not just my family, but all the families, all the little girls handing their grandfathers mints and all the grown sons singing in the dark of the car. We need our beginnings reflected, sure, but also our long, drawn out ends. That would be the fuller, braver story for all of us.

*Bearscat13 is, in fact, one of my mom’s passwords.

Gorgeous piece, Courtney. I'm 66 and dealing with my dad's dementia, so long past the sandwich generation. I have so much admiration for what you're doing and for the loving way you write about it. My dad, who is 93, is in memory care (a wonderful place -- they do exist) and taking a very mild anti-anxiety medication, which helps a lot. I don't see him every day, but I struggle every day with my husband and sister to manage his questions, his finances, his health care, the emptying and sale of his condo. I think most people don't have the team you've assembled to take care of a loved one with dementia or the money to cover the costs of memory care. They just do it. Too many build up a lot of resentment, lose a lot of themselves, quit jobs to make it slightly more manageable. Some see the pearl, some don't. Many become very isolated. I agree that we have to bring this experience, this struggle, out into the open. And we need many more affordable, caring ways to deal with this epidemic.

Courtney - I so love and honor what you are doing and the writing about your family's experiences. It is very much needed now. Please keep doing it even though I know it's hard to write about and hard to find time. We spent 10 years with my mom at home with dementia while our daughter was growing up and the love and understanding that we all gained during that time has made our child a strong and caring adult. Also, there are nursing homes that do provide incredible care. Not many, but they exist. I looked at literally 50 before I found one - my mother had been "escaping" from our house and was convinced that someone was trying to kill her - it was too dangerous and more than we could handle. Fortunately, we found a safe, loving place where they were very skilled at balancing her meds. We integrated there with this big amazing family of nurses, patients and families like us and it was a godsend. I can honestly say that my mom's last years were her happiest. It can be done, it just takes people who care. And there are still people who care. Bless you and your family! Thank you so much!