Inspired by #sharethemicnow, I asked one of my favorite writers to take over my newsletter this week. I first learned of Joshunda Sanders gift when she submitted an essay to an anthology I was co-editing. I was so taken with the images she painted and the insights she possessed, that I asked if I could meet her in person the next time I was in Austin, where she lived at the time. I remember sitting in the diner booth across from her, falling hard for the women behind the words. She’s whipsmart, deeply literary, gorgeous, and a rare mix of gentle and fierce that make me trust her instincts better than just about anyone’s. I have continued to devour everything she writes, including her own newsletter (which you should definitely subscribe to). Without further ado, a reflection by Joshunda Sanders in anticipation of Juneteenth…

I am an obsessive reader because I write directly from a reservoir of deep delight in the discovery of what is in my soul. I am always trying to figure out what I am doing here – on the page, on the planet – reckoning with thinking too much about myself and feeling too much for other people. An unboundaried childhood will do that to you, I guess, but what that has looked like in self-isolation during the pandemic has been a deeper engagement with texts as a way of seeking salvation and comfort.

Like most Americans, I am deeply nostalgic for an uncomplicated past, even though (and perhaps especially because) everything about my past, our past, is so complex. Like most Black people, I am abundantly aware aware of the awkward contours of this nostalgia, so I declare it as a kind of reverence for all that my ancestors did for me to be able to sit, free, at my kitchen table and declare to a nation in revolt against the shackles that continue to oppress us that we are entitled, too, to joy and love in the after times.

One of the first books I devoured in March was Eddie Glaude, Jr.’s book, Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own which is scheduled for release in the coming months. It was my first encounter with the phrase the ‘after times,’ which Dr. Glaude says comes from Walt Whitman’s Democratic Vistas in 1871. He wrote (in the uncorrected Advance Reader’s Copy I read):

For Whitman, out of the ashes of the Civil War emerged a nation bustling with the energy of commerce, ‘endowed with a vast and more and more appointed body’ but ‘with little or no soul.’ In this context, national rage and fury served as warning signals that were ‘invaluable for after times.’ The phrase refers, at once, to the disruption and the splintering of old ways of living and the making of a new community after the fall. The after times characterize what was before and what is coming into view.

We are certainly in the after times now, when the celebration of liberation for the last Black enslaved people – Juneteenth – has taken on such increased widespread significance, along with the massacres like that of the 1921 Tulsa, Okla. Massacre, that the man I reluctantly refer to as our President has to pick another day to desecrate because now it is protected. I remember, in my early thirties when I worked as a reporter in Austin, learning about Juneteenth as a Texas holiday that seemed of broader significance to Black people everywhere certainly. A decade later and here we are.

And of course, we are, again, declaring as a more multiracial coalition, now, Black Lives Matter. I spend these early days of the after times thinking of Ella Baker, who reportedly said:

Until the killing of Black men, Black mothers’ sons becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s son, we who believe in freedom cannot rest until this happens.

As the title suggests, I have been wondering about when the best moment is for Black people, in particular, to rest our weary souls. To rest, period, feels like an incredible luxury. Do we not stand on the shoulders of the ancestors I mentioned before so that we continue doing the work, our work, everybody’s work?

I used to think my ministry was overwork. Free labor. Taking on the burdens of others. A true pandemic gift has been surrendering old mental shackles and, in the slow down of these after times, really looking at ways I have allowed others to burden me with their guilt, their expectations and insinuations. I have learned that what liberation for me looks like is to take a damn nap. I play an extraordinary amount of Mortal Kombat. I also do all the adult things that need to happen in order for survival, especially now. But I also crank up my Tidal playlists and shake my shimmy.

It was Lama Rod Owens (yes, another book plug is coming) author of Love & Rage: The Path of Liberation Through Anger who offered the wisdom I had been waiting to hear – permission, really – in a BIPOC conversation last week. Rod said something to the effect of: I think our ancestors cheer when we get to sit down because they never could.

This brings me back to Juneteenth and what it must have been like, in the soaring heat of the summer, which, for the enslaved working on farms or plantations, were among the longest, most grueling times because they worked as long as the sun was up. How sweet the celebration must have been for them to throw down plows and heavy bags and burdens and walk toward their freedom. I wonder, all the time, how their invitation to the radical joy of those after times played out.

For me, radical joy in this moment has so many looks, so many faces and scenes.

The obsessive reading provided me a lot of solace and room for meditation until my body was so filled with words and contexts and rage that I spilled out to protests in the Bronx. The first was a watershed moment for Bronx protests in the time of COVID-19, and we were kettled, the police shown rioting, violently tear-gassing protesters and arresting many of us for breaking their dangerous curfew. I was physically unharmed and I made it home safely, but I was so rattled that I realized it was time to get my will in order. The second was a peaceful protest in Van Cortlandt Park, where I arrived with the goggles and the extra mask I had from the first in my bookbag, just in case. Both times, I felt, for the first time in so long, a real understanding of solidarity; what exactly it means to rest in the arms of a community that holds you, that loves you, that wants you to stay alive.

As I self-quarantine with the hopes of visiting family soon, I am also abundantly aware that on the page and especially off, freedom in the after times always includes the free will to do the wrong thing – I am thinking especially of the men I see everywhere without masks whenever I venture out of my house. Maybe they have always felt invincible, maybe they always will, but they mostly make me angry because of this brazen show of lack of care.

And as soon as I start to spin out, I remind myself that self-care and Black joy is my contribution to these after times. That there is room for both protest and movement and rest, so much rest. Long phone calls from my landline (!), yoga on Zoom when the babies are unmuted accidentally, the loudest Bronx birds tweeting delight their songs can echo through empty streets, cookout music though I am near not a single grill as I dance with the spirits to the Cupid shuffle. When we find ways to replenish and liberate ourselves, we can indeed, begin again to free others.

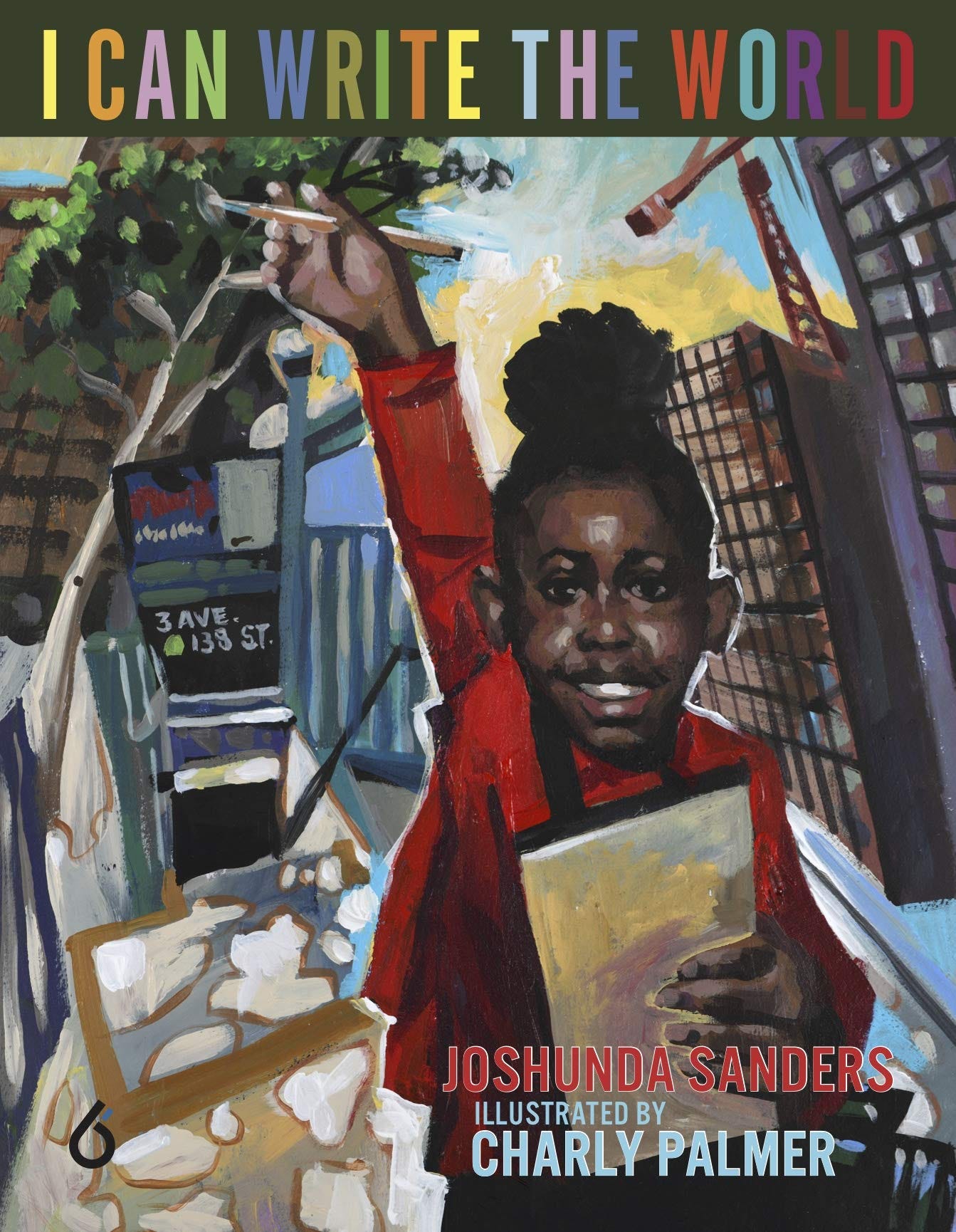

Order Joshunda’s book, along with a few others by Black authors, from Black-ownded bookstores this week, to be a part of #Blackoutbestsellerlist week. Some of my more recent favorites: Eloquent Rage by Brittney Cooper, The Book of Delights by Ross Gay, The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson, Ghosts in the Schoolyard by Eve Ewing, Always Another Country by Sisonke Msimang, and Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown.

No Q&A this Friday. Thanks to all who have been giving such great feedback on the series thus far. It’s fun to see the club of admiration grow for the incredible humans I’ve been interviewing.