At dinner Maya announced that some boys in her class had gotten in a fist fight in the hallway outside of their classroom door. I imagined the hooks with their chaotic jumble of backpacks and coats, the bin on wheels filled with lunchboxes, and then a blur of boys, pushed up to and over some kind of edge.

“Did they get in trouble?” Stella asked, eyes wide with the heightened stakes of second grade. “What did your teacher do?”

“She sent them outside to the playground to figure it out,” Maya said.

“And what happened?” I asked. Now I was the wide eyed one. The incessant talking I’ve done as a parent to help my daughters solve their fights flashed before my eyes. Could I have just said “Work it out,” this whole damn time?

“They did. They made a contract with one another,” Maya replied matter of factly.

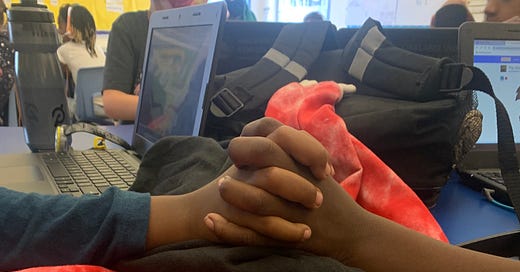

True story. A second grade teacher sent a bunch of boys onto the blacktop and they had the internal resources to not only calm down enough to make an agreement about their future handling of said edges, but write a contract to that effect, and sign it. A couple of days later, when I stopped by the classroom after my library volunteer hour to drop books off, a couple of these same boys were doing their reading app on separate tablets while holding hands. Again, true frickin’ story.

I’ve been noticing the way that kids repair lately. It’s so artful, so surprising.

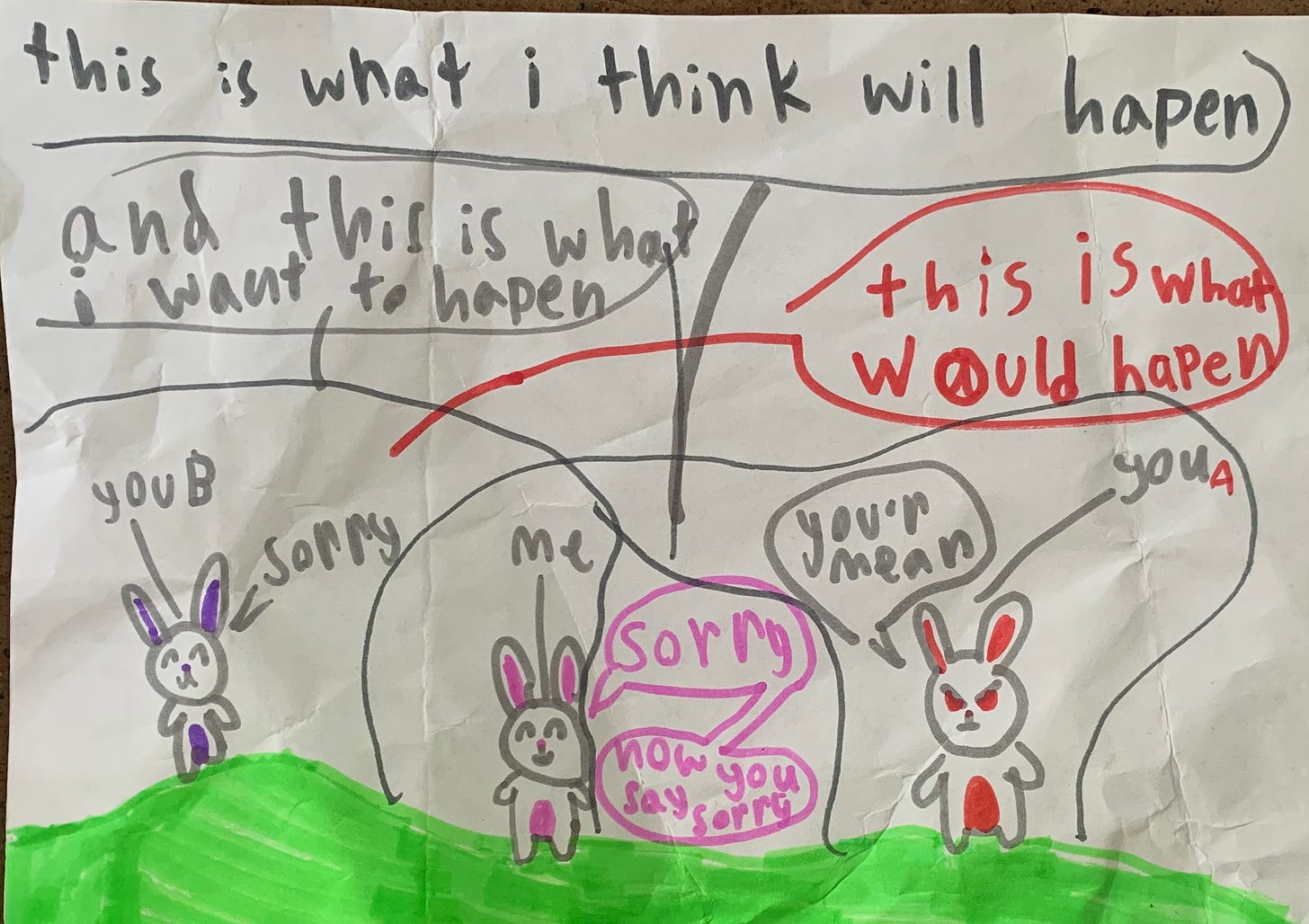

Maya and her buddy have been getting in some quarrels, too. They’re both very sensitive and the relationship is charged with that best friend necklace-type intensity–so delicious and so terrifying. Maya’s friend is pretty quiet, particularly when she’s upset. One afternoon, as I was pulling crumpled drawings, sticky ziplock bags, and other detritus out of Maya’s backpack I found a piece of paper with two little bunnies drawn on it with dialogue. The bunnies were apologizing to one another in various scenarios. The scenarios were labeled: this is what I think will happen, this is what I want to happen, and this is what would happen. When I asked Maya about it, she said that her friend felt too sad to talk about their conflict so they decided to draw it out. Essentially they reinvented couples therapy as cute graphic novel–their favorite genre. Kinda genius, right?

I imagined all the times that John and I have tried to fight like rational adults and spilled right over our edges, how wedded we are to words. Well, me especially. I think he’s actually wiser about their limitations, but not me. A reader and a writer through and through, in moments of tension I tend to talk everyone in my family to death. Maya and John, who are not particularly verbal, are sometimes held hostage by my attempts to make sense of our feelings, to force them into some kind of neat, narrative structure. Their skin goes pale and they retreat into themselves. I get flushed and talk even more. I think the experts would say my love language in these moments is–make-me-feel-safe-and-capable-by-turning-this-into-a-well-made-play! and theirs is leave-me-the-hell-alone-you-invasive-goddess! It doesn’t go well.

Suddenly I’m seeing the pattern everywhere. When I let something other than talking be the dominant medium, the light gets through. John and I have tried to go on evening dates like all the books say you should if you want to keep liking one another. And it’s nice to have a meal without a meltdown, but sometimes I think of all the things we need to talk about–logistical and philosophical–and I just don’t have it in me. Instead, when we go on a hike on a Sunday morning, our bodies moving up a big Berkeley hill, something shakes loose and we can hash out even the harder topics. Maybe it’s time of day, but I also think it’s primary mode. Movement makes us brave, just like bunnies make Maya and her bestie soft.

Repair is hard. We can see that in every level of our lives, from the most intimate to the most political. It requires having some perspective on all of our most precious ideas about ourselves–as innocent, as misunderstood–but I like the idea that even the hardest things, the places filled with landmines of blame and shame, can be faced with honesty and creativity. I want to punch you in the face, but I also like you. I don’t want to talk anymore, I want to draw. Let’s move and see what kind of love we can remember.

I think about the organizations that are doing this work—The Armah Institute for Emotional Justice, which uses, among many tools and frameworks, theater to help people understand the gendered and racial harm that their organization’s cause, and the Decolonizing Wealth Project, which helps philanthropists and grantees face the brokenness of our current system by actually making space for grief and other messy emotions. I think of Ear Hustle, that uses audio and art to illuminate the inside of a prison and the inside of human nature, our struggles and transformation.

I think about the time I apologized through a short story to my childhood best friend or the time a dude in a gold chain and Adidas tracksuit sobbed through an entire yoga class. I think about all the people we give up on, including ourselves, when maybe sometimes what we needed was only a sacred shift in approach—something less direct, something roundabout, something corporeal. Sometimes we need to take the long, circuitous way home to ourselves and each other rather than following the algorithmic directions for the most effective route. Kids get that. Adults forget that. I know I do. Here’s to inefficient, artsy, childlike apology. Here’s to repair as multidimensional as we are.

Share this post