'One side can't do it alone'

5 questions for Dr. Noliwe Rooks on integration and the mindset of White parents

“Educational apartheid has high social costs…we can right this wrong, but first we have to take full account of the ways in which race and profit-driven interests in education have negatively impacted the futures of so many of our nation’s youth.”

That’s Dr. Noliwe Rooks in her seminal book, Cutting Schools—a work that has had a tremendous impact on me. Noliwe, who I first met almost ten years ago, is a ferocious intellectual, a curious soul, and a joyful laugher. She has pursed her academic passions with a justice-oriented pragmatism (earning her the appointment of Chair of the Africana Studies department at Brown University), and even turned the lens on her own family and the way in which its triumphs and tragedies have mirrored that of this unfinished American project.

I caught up with her because, in the lead up to my book’s release, I am excited about introducing you all to some of those that have shaped my thinking most profoundly. Here’s Noliwe…

Courtney Martin: You’ve been writing about educational inequity for a long time. I’m a newbie. One thing I noticed was how vitriolic the space is compared to other setting in which I’ve reported. There seems to be a tremendous amount of blame and drama. Do you have a theory on why that is? Is it just because our kids are involved and people have big feelings about their kids?

It’s hard to shape the images of those rooms full of yelling parents demanding that things stay the same. Segregation harms us all. We fear what we don’t understand, and too many of us lead segregated lives that heightens those fears.

I remember reading something you wrote in your last book about how you wanted to live a life with “just enough”—that you were not striving to have more than any one person needed. I think those people who want more, who hoard, will not believe that there is such a thing as a fulfilled life with “just enough.”

I think that you’re trying to live those ideals and to share them with your children—your children who gave you the courage and strength to make choices so very different from so many White parents in your situation.

What do you think most people don’t understand about the fight for integration in this country?

I think that most people don’t think much about integration at all. I’m not sure we notice how segregated so many of our neighborhoods and schools and cities are. I think some of us have assured ourselves that we are “color blind.” We stop grappling with how often we tend to live with and worship alongside and attend school with people who share the same skin color and social status.

Somehow, within that conformity we manage to see “diversity.” We see that some of our friend group like to surf, and others like to swim, and others are afraid of water, as a kind of “diversity” and we then downplay the racial and economic types. Or we give into our discomfort with really thinking and talking about structural inequality.

In reading your book, I keep thinking of some of the parents who attended the private school open house that made you so uncomfortable, but offered a particular kind of homogeneity, exclusivity, and comfort that so many parents actually want for their kids.

The “diversity” in those spaces becomes a stand in for actual racial and economic integration. Those parents don’t get the difference between diversity and integration.

In your book, Cutting School, you write, “In the absence of such a widespread commitment and effort, integration as a cure for the disease of educational racism is, in the twenty-first century, tantamount to a prescription that can’t be filled.” I find it particularly interesting to think about this in relationship with Rucker C. Johnson’s assertion that “The medicine that is integration works.” In other words, are you saying that we know integration would actually work to break the cycle of poverty if there was a genuine public commitment to it, but because there isn’t (and maybe never will be?), it’s disingenuous to hold it up as the cure. Is that right? Or do you have doubts about its ability to break the cycle of poverty even with widespread support?

I think that the ideals of inclusion and of sharing resources are what undergird the idea of integration. In the places where integration has achieved both—inclusion and shared resources—for longer periods of time, there is an impact on poverty, higher levels of educational attainment and achievement, and access to higher, better paying forms of employment. These outcomes are well documented and supported in Professor Johnson’s work.

In addition, I think in places where integration has been implemented and succeeded, you also see more, not less access to voting rights, and more progress in achieving a multi-racial and multi-status democracy. We also must pay close attention to the fact that, almost as is true with chronic diseases like cancer, we need to make sure that just because the illness was cured once with the integration medicine, that it hasn’t returned.

I think we need different strengths and doses, and combinations of treatments to keep the sickness at bay. We don’t really do this and when we don’t, we see districts that managed to achieve some sort of stable integration, reverting, or we see White families opting out of the public system and into private schools in the ways you describe in your book.

That is one of the reasons I am such a fan of your book. I feel like it’s coming at the integration “cure” from a different angle. I think it’s showing how the success of integration just cannot always be borne by Black children and Black families. It is sort of like a marriage, or partnership, or lifelong friendship—both parties have to work at it and when necessary, fight for it. One side can’t do it alone.

You were the very first person to offer me an endorsement on my new book, which was—and I don’t use this word lightly—a blessing. You started by saying, “This is a book for which I have long waited.” What did you mean by that?

For the longest time I have wondered what is in the minds of, to invoke the title of a popular podcast from last year, “nice white parents.” What are they really thinking regarding the decisions they continually make about the education of their children and the absence of care for how their choices impact and narrow the options for the children who are not theirs? I could surmise, intuit, and curse their motivation, but I honestly couldn’t really express it in a way that might move them towards understanding.

I think that your book takes us into the contemporary mindset of those parents—their fears and discomforts and awkwardness, their desire for status—in a way that clarifies their choices and commitments.

Though I have long wanted your book so that I could see more clearly the process of how those threads get woven, I also think White parents need this book to seem themselves more clearly. I think it takes someone like you and like this book to, I hope, help other White parents see themselves and their impact on others. It may not lead them to other choices, though I hope it will, but I hope it will make it more difficult for them to evade themselves. I hope it will disrupt their claims to innocence.

You’re working on a new project that looks at the ways in which integration efforts throughout the last century in America have been intertwined—for better and worse—with your own family’s story. What is it like to write such personal material as an academic?

Really hard. I need tips! I keep asking myself why I didn’t just decide to do me and my kid, and not back up to my grandparents and parents, which means I must include history in ways that balances out the personal. I should have just determined to follow your lead!

Ha! Dr. Rooks, I’m following yours obviously. And I cannot wait to read that book. What a contribution that will be. Thank you for everything.

We are donating to the Zinn Education Project at Dr. Rooks’ request.

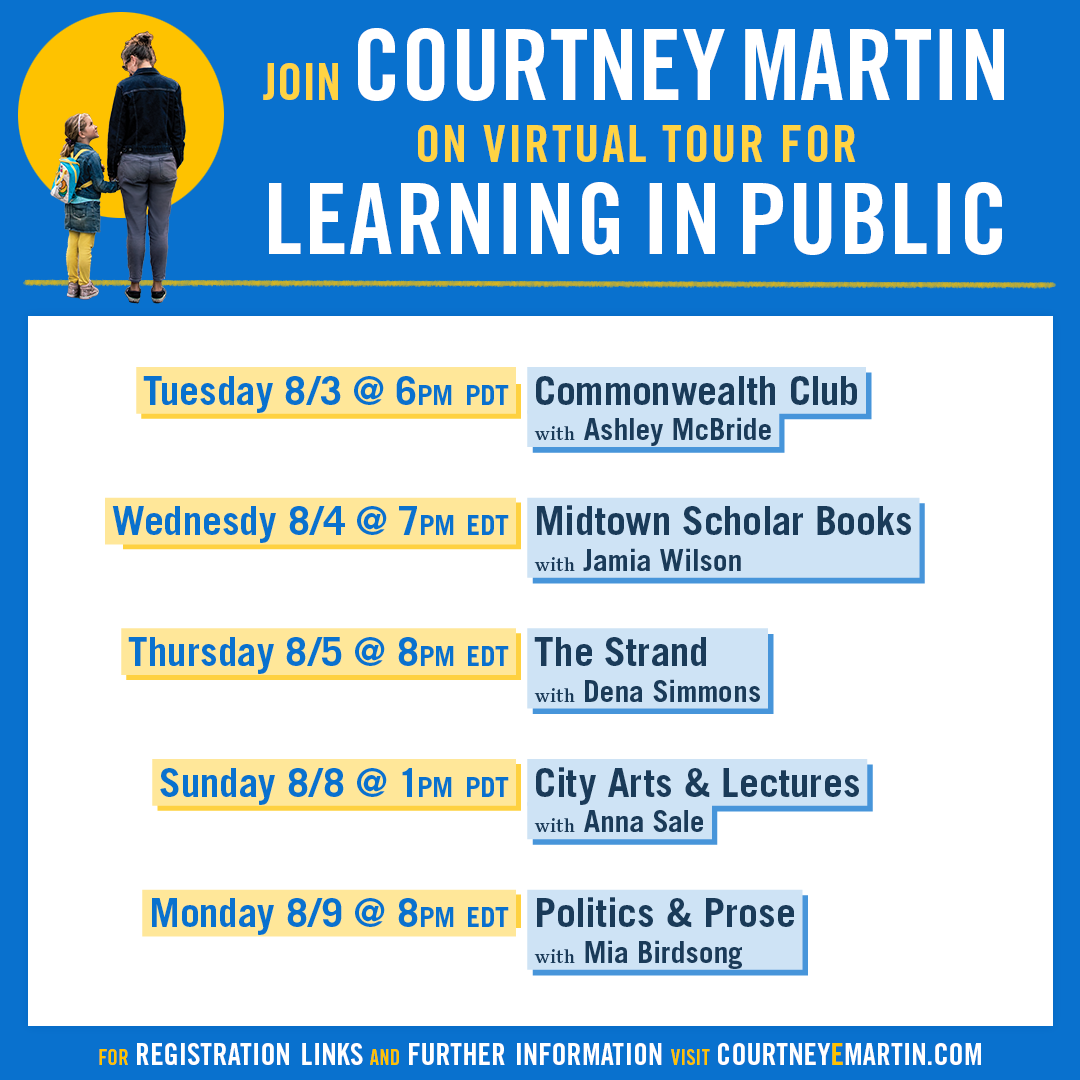

Book stuff next week—join me! For those who are in the Bay Area, I will be on KQED’s Forum on Thursday morning if you want to tune in.

Mmm, thanks for introducing me to Dr. Rooks and her work. I'd love to see more reflections weaving those themes of scarcity, enoughness, and fear... do you do it in your new book?