As you know, care is one of my obsessions. I’ve reported and written on it, done a bunch of narrative change work on it, and, well of course, lived it (both as one who does a lot of caretaking for others and who has been cared for and continues to be cared for by others).

When you meet someone who has been exquisitely and consistently taken care of, especially from a young age, you can feel it emanating from them. It’s intangible, but unmistakable. It’s a suppleness, a confidence, sometimes even an earnestness bordering on obliviousness that only seems possible from someone blessed in this particular way. (It’s not, by the way, about class. I have experienced people who were brought up in the shadow of major poverty who give off this sense, as much as from people who grew up rich.)

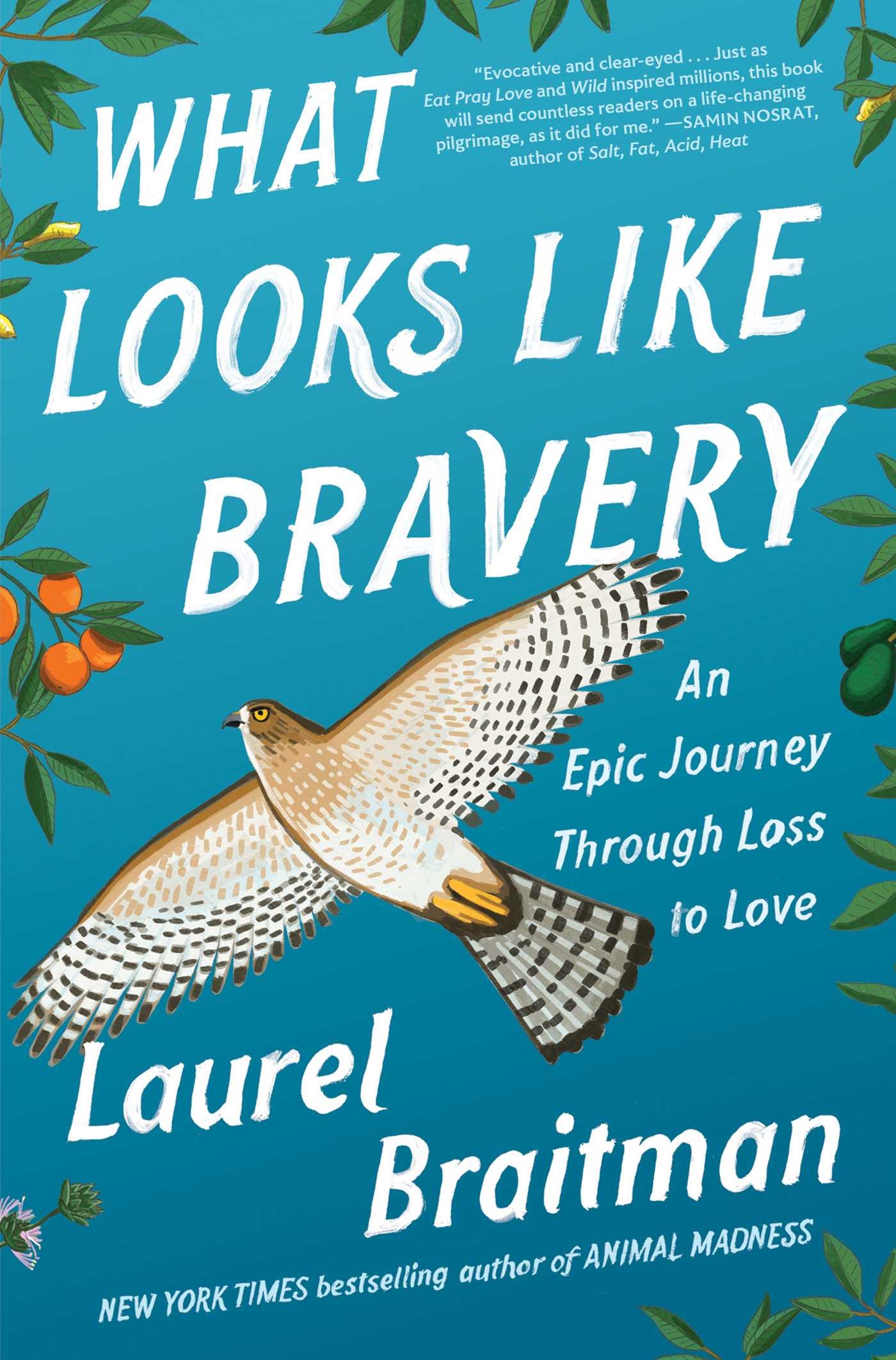

Laurel Braitman is brilliant as hell, and gives off that vibe of someone who has been thoroughly and imaginatively loved. You feel it the second you meet her. This is important because her new book is very much about this experience, and what happens when you lose the source of that love…over and over and over. As we all will. As we all do. Because, life.

Laurel’s book, What Looks Like Bravery, dropped last week and I can’t wait for you to read it and tell me what you think. In the meantime, check out this beautiful back and forth we had recently. See you in the desert soon, dear L.

Courtney E. Martin: One of the main points of this memoir is that what looks like bravery is often very small and relational. You were a person who achieved at a high level and jumped into adventures fearlessly, but realized you were running from some pretty big feelings. How does one know whether they are being authentically brave or just doing what society sees as brave?

Laurel Braitman: I’m not sure the difference is obvious from the outside. For me, bravery didn’t come from doing the things other people often thought took courage: studying grizzly bears in remote Alaska, going to the Amazon by myself to spend months on riverboats before I was old enough to drink, or even doing my phd at MIT despite being a horrendous math student…those things may have been challenging, but they didn’t scare me. As my very good therapist told me, you can’t be courageous if you’re not scared. And what scared me was feeling my own sadness, regret, shame, anger.

As I say in the book—what bravery looks like is often us being scared of something else even more. Luckily, for better or worse, the world just keeps on offering us chances to act with courage.

A lot of this book is about the body--your early obsession with medical textbooks, your father, the heart surgeon, your return to your body when you finally wanted to face your grief and guilt. You are such a heady person, as am I. As are so many readers. What kinds of practices do you have these days for getting back into your body?

This is the hardest thing for me. My husband is annoyed by it and will say “I see you here, but you are not here.” It is true. I’m usually somewhere else—the future, the past, inside a list of emails I need to respond to. And as you say, a life of the mind only reinforces and rewards this tendency even if it’s not making us happy exactly. I used to joke, back in grad school, that the institution just wanted us to be brains in jars on skateboards. The body and its needs can be a liability that keeps you from constant intellectual work. I’ve tried meditation and it’s nice and I’m sure I’d be a better person if I was practicing it regularly.

But for me, the thing that has always grounded me is going outside. It can be an urban or a wild place. As long as I can see the sky and I leave my phone at home, it works. Being outdoors reminds me that I am small. You’d think that would be a bad feeling but it’s not. It’s comforting to see yourself as just another thing in the world among the sticks, the rocks, the streetlights, the seagulls, the clouds. It makes me feel part of the weft of the world instead of all alone hunched over my task list wondering if I will ever do or be enough.

This book is as much about the body as it is about place--the avocado ranch in California where you grew up, especially, but also a cabin in Oregon, and the dark mornings of Alaska, and the gorgeous deserts of New Mexico, and an Italy writing residency we have both been stupid lucky enough to attend. How do you think our landscapes and our grief intertwine?

Sometimes it’s comforting when an exterior environment matches your insides. After a wildfire took nearly everything I loved, for example, I didn’t want to shower and change into clean clothes, and I didn’t want to look at anything other than an ashy, smoking, debris field. Anything else felt like a lie. I was bereft and wanted to look at destruction.

On other occasions–after I’ve lost people, or gone through tough breakups, even a beautiful sunset can feel like a taunt. “How dare you?!” I’ve felt like screaming at the sky. But eventually, this feeling transforms into something else and at some point, I’m ready to be knocked over by the beauty of the world again.

This has always happened for me in the American West. I’m a child of sweeping vistas and sparsely populated places. In the book, the reader comes with me to many of them. Alaska, especially the Bering Sea in winter, is one. And when I was there I was in period of time in life in which I wanted to be brutalized by the darkness and the cold because that’s how I felt inside. But, despite my best intentions, I was surprised by love instead.

If we’re lucky enough to live in, or travel to, places that inspire awe (and I think that any place can do that if you’re open to it) then we will confront our feelings in the landscape. We are meaning-making animals and probably since the beginning of humanity we have used our surroundings as signs, symbols and teachers to make sense of our lives. Perhaps we’re not navigating by the stars as much as we once did, for example, but we’re still reading our horoscopes, or gazing through telescopes to understand our planetary history. It is vital to look outwards in order to think inwards and landscapes are full of the kind of metaphor that helps us understand ourselves.

A friend told you “Guilt is only helpful once.” That line took my breath away. Please explain.

Oh yes, Suzi Golodoff, a very wise birder in the Aleutian Islands! She really is so wise. She told me that guilt is only helpful once, in the exact moment in which you realize “Dang, I really shouldn’t have done that.” In this moment, the guilt is useful because it’s teaching you that the thing you just did wasn’t great and maybe you should not do it again. After that though—if you continue to feel it, it’s not helping you do a damn thing. It’s just a blunt weapon you’re unproductively bludgeoning yourself with.

I still feel guilty all the time — for big and small reasons– but I am not the same person that I was before I wrote this book. Now I know that, in my case and maybe for many people reading this right now, feeling guilty is what we do when we don’t want to believe we have no control over a given situation. If you lose someone or something–whether it’s a person or a job or a relationship—the world can feel scary and illogical. Feeling responsible for the bad thing happening is a way of imposing order, even if it’s making you suffer. “If only I’d been/done XYZ, maybe this wouldn’t have happened, or wouldn’t hurt so much” you might tell yourself. But really, the guilt is an alternative to what is perhaps more honest: that something bad has happened and there is no one to blame at all. It just is.

Write an endorsement from your late dad for this beautiful book. What would he have said made it great?

“I’d rather Laurel was writing popular history or political thrillers, but I’ve known she was born to be a writer since she was a kid. Also, this book doesn’t lie about what I think matters most: life is always too short if you’re doing it right; never take your loved ones for granted, and choose to die on your own terms if you have the chance. And Laurel, if you’re reading this, stand up straight dammit.”

I think he’d probably also say, “I told you so” while grinning. No one has ever believed in me to the extent my dad did. He loved me in a way that was like being loved by the sun: incredible and life giving, and also if you’re not careful, capable of burning you alive. His unwavering belief in my abilities, even when I had none, was a blessing and a curse because I felt his expectations not as suggestion, but as requirement.

Most importantly though, I hope he’d see this book as confirmation that he was successful in what he set out to do. He spent years trying to prepare my brother and me to go on without him, teaching us that our dreams were a compass we could follow towards a life of meaning and purpose. I think it worked.

We will be donating to Saddle Up and Read (horses! books! literacy!) in honor of Laurel’s labor. Buy her book here.

Courtney has characteristically managed to conduct another absolutely riveting interview! Of course, Laurel Braitman is brilliant, we know that from her amazing book. But there are many new ideas expressed here that stand out even for one familiar with her writings. For instance, the categorical imperative to break out of everyday routine for a trek into the woods, without a cell phone. This evokes the vital concept of what Japanese studies have called "forest bathing." Fortunately, Sharron and I live within a 10 minute walk to a conifer forest, the largest urban forest in the U.S. (Shout out for Portland, OR., as Courtney knows from visiting us here).

Even in bad weather, this enables us to "bathe" in the woods, as we absorb the healing elements from tall pines (see Thoreau's marvelous essay on "Maine Woods") . We can journey silently into ourselves in the way that Laurel Braitman magnificently conveys as a dynamic force in her life.

Sure, this can be achieved in the city, but after living in Manhattan for 30 years, we never felt a similar experience. So, walk--don't run or drive--into the depths of the forests, people of all ages, and leave behind your cells! DD

"our dreams were a compass we could follow towards a life of meaning and purpose."

If I can instill this belief in my sons, I will have won life.

I do hope I'm/we're loving them in such a way that they become some of those radiant beings you describe in the introduction.