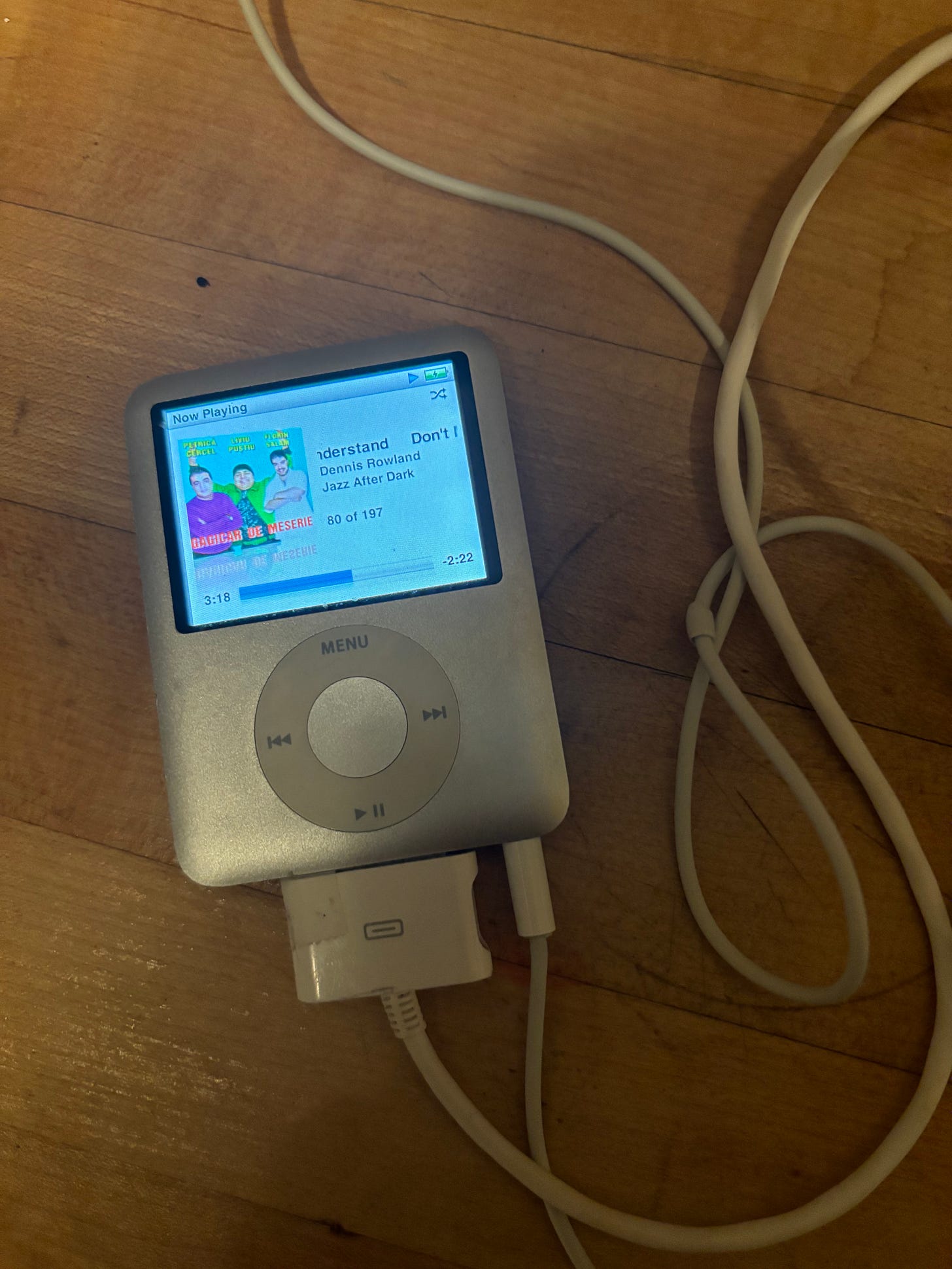

My dad may be one of the last people on earth to religiously carry around his iPod Classic, a 2007 model of the legendary music player that most people shed to the landfills long ago. He puts the slim device in the small pocket of his jeans, threads the headphone wire up under his fleece jacket, and sticks the earbuds in his ever growing old guy ears, where they will stay—off and on—the whole day long.

He has dementia, so has lost so much in the last few years, but this throwback listening device and his love of music are a constant. When he puts in his earbuds, he enters an aural world where his old friends—John, Paul, George, and Ringo, Aretha, and Marvin—ask nothing of him. They serenade him and delight him and remind him—if not of who he exactly is or was—at least how he likes to feel.

This last week I spent a lot of time with my dad. It’s been a week of trauma and triage over here. I have been in a what feels like some kind of prolonged shock state—functioning, functioning, functioning but not feeling a whole lot other than overwhelmed and relieved. One feeling that has broken through in a huge way is gratitude, and in particular, gratitude for people who—like my dad’s musical friends—know how to be kind and flow with him, a man whose brain is not of this world (“this world” being fast-paced and word-filled).

My friend Neela, a palliative care doctor with a gorgeous, wild mane and a voice that feels like it comes out of some place knowing and loamy, brought two pizza pies, some salad, and just the right amount of fancy chocolate bars one night for dinner. My dad had just spilled a tiny glass of Old Caz IPA beer that I poured for him. I get great delight out of feeding my dad things that I know he used to love, but couldn’t have when he was suffering from chronic migraines; dementia has eradicated the migraines. I said, “No big deal, Dad,” and poured him another.

Neela and I got to talking about the recent conference she’d attended in Santa Fe on death and dying, wildly at the same retreat center where my dad and I once did a silent meditation retreat for his 60th birthday (what feels like many lifetimes ago, now). And then my dad spilled his beer again. Neela asked for a paper towel, cleaned it up quickly and thoroughly while still chatting, and then poured him a third glass of beer. This seemingly subconscious orchestration contained not one ounce of pity. Later I texted her, “Is pouring a little glass of beer for a sweet old man a form of palliative care?”

She affirmed, explaining that palliative care is basically just “the simple way of being gentle and kind.” Well, amen to that always.

After Neela left, I laid the pizza on the picnic table in the courtyard and invited our neighbors to eat dinner with us—we had plenty to share. We sat around and chatted about chronic mysterious illnesses and the exhaustion of parenting, all while our kids buzzed around us, fighting over the hammock, eating pizza sloppily, and drawing on the sidewalk with chalk. Our neighbor girl, the sweetest three-year-old you’ve ever met, gave my dad a drawing of a narwhal, informing him that she only draws one a day and today he was the lucky recipient. His eyes grew wide and he said, “Thank you so much,” clearly touched, though who knew for how long.

When we started talking about my dad’s first car—a ‘55 convertible Chevy, mint green and yellow with fuzzy green dice hung on the mirror—he did something he rarely does these days; he tried to get in the mix of the conversation. Sometimes what he said made just enough sense. Sometimes it didn’t. These are moments when he will often rely on hand gestures and facial expressions to get his point across. For me, these moments are such an indicator of how feelings remain for him, even as words leave; he’s trying to make the feeling with his hands and his face.

Our neighbors nodded and affirmed along the way as our conversation took unexpected turns into vintage car performance art. They didn’t ask pointed questions, like “What are you trying to say?” or give him feedback he wouldn’t have been able to do anything with, “I’m not sure I understand what you mean.” They flowed with him—the simple way of being gentle and kind. Turns out, a couple of engineers can be palliative care practitioners at the picnic table on a sunny Wednesday, too.

Spending this time with my dad, I’m thrust into a deep yearning for the world—writ large—to be more palliative. Which is to say I so long for a world where his suffering is not compounded by the expectations of a society that pretends that disability, disease, aging, and death don’t exist. I know this is not a unique or new epiphany, that so many have said this in a million beautiful and profound ways before me. But the visceral feeling of wanting your people to be handled gently by the world, and seeing how easily and often that is not the case, is a new way of knowing all of this for me.

In some ways, a more palliative world demands huge systemic and structural change. But in others, it only demands the tiniest of personal shifts. Walk slower. Laugh alongside. Pour a small glass of beer. Pour it again. And again. Don’t ask questions someone can’t answer. Play the old music. Notice what and who is right in front of you. Give art. Never pity. Simple and sacred, be gentle and kind.

I’ve been fortunate to experience a palliative world because my mom’s partner did not over protect my mom. They traveled the world, went grocery shopping and more until the last couple years of Alzheimer’s drew her into that strange husk. Even then it was possible to see my mom in her essence and treat her with dignity. It was all, of course, a long dance with grief. I was grateful to find that singing, music, dance, art and laughter were the best medicine for her and everybody around her! Thank you and bowing to your heart of love for your dad and all of us.

Oh my. What a lovely, lovely piece. It pierced me right to the heart this morning, with all its gentle sweetness. You gave me the precise words to an ache that I have been feeling, more or less, for what feels like such a long time: "...a deep yearning for the world—writ large—to be more palliative."