Existential debates in the minivan

what my dad's dementia has taught me about non-attachment and the "self"

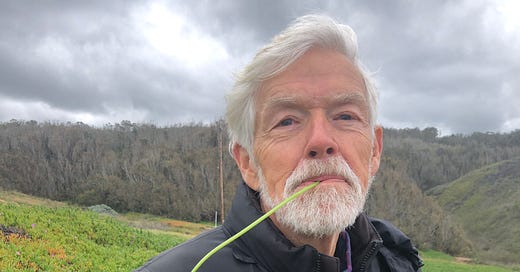

First off, I just have to say a giant, weepy thank you for your response to my newsletter last week, in which I disclosed my dad’s dementia diagnosis. The comments were so comforting, generous, and built a sense of profound solidarity for me unlike anything I’ve felt so far during this experience. I’ve been wrestling with whether to “go public” about this experience for a long time and your response was so heartening and healing. As you can see, I’m riding that wave of generosity right into this week’s dispatch. Thank you thank you thank you.

One of the topics that my dad and I used to talk about more than any other was Buddhism. From the time I was in high school, wearing pastel chiffon scarves tied around my neck in tribute to Pretty in Pink and reading existential novels before I understood what existentialism was, I was asking about and sometimes challenging my dad on his spiritual beliefs.

Born in 1948 to a mentally and financially fragile family in Denver, Colorado, my dad grew up going to Catholic Church. His mom was an intellectual, who loved reading The New Republic and dreaming about my dad one day being president. His dad was a traveling salesman who would hit the road for weeks, riding hazardous bust-and-boom cycles of success and failure. I imagine the church-going was an attempt on his parents’ part to create some kind of stability.

But my dad never felt at ease in the Catholic Church. He would often joke in later years, “When I realized that I would basically have to confess all my sins, walk out of the church, and immediately get hit by a bus if I wanted to go to heaven, I decided it wasn’t for me.”

What was for him was Buddhism—a religion he discovered in his 30s (my mom can’t remember exactly when, but wonders if it was seeded at a Jack Kornfield workshop they went to in the late 70s or early 80s). My own experience of my dad’s Buddhism was minimal. I knew he woke up before the sun and meditated, but I never actually saw it; the only evidence was his dense round, rust-colored zazen pillow. I noticed his steadily growing collection of Buddhist books; my dad was always a slow, methodical reader, highlighter in hand, really taking in every word of a book, while my mom blazed through book after book at a daunting speed.

He did keep a red letter edition of the Bible next to his Buddhist books—the version that has all of Jesus’ words highlighted in red; when Evangelical Christian influencers like Focus on the Family and the New Life Church were distorting Jesus’ teachings in all kinds of visible ways to his teenage daughter in Colorado Springs, he made sure to explain that Jesus could be read directly and had very loving, non-judgmental things to say about the same people James Dobson and others were vilifying.

My parents took us to a progressive Christian church briefly when we were small, but drifted away from it, so we were largely raised with no formal religion and no affiliation with any religious institution. Hungry for a more structured ethical framework to fall back on in a world I experienced as often cruel and full of hypocrisy, I remember checking out books on all the world’s major religions from the local library; I thought choosing a religion was like ordering from a philosophical menu—an exercise of the mind, not the spirit or the soul. I remember reading about Hinduism, in particular, and thinking, This is pretty great, but can a White girl living in Colorado Springs just sort of decide to be Hindu?

My dad’s very private Buddhism really appealed to me, so I tried to start drawing him out on it more often in our weekly trips to the supermarket. I liked so much of it, particularly the emphasis on mindfulness and non-harming, but some of it sounded incredibly harsh. In particular, my teen sensibilities were deeply offended by the idea of non-attachment.

Which makes perfect sense to me now as I look back. The developmental project of adolescence is basically attachment—create and tend to an identity (attachment), bond with others and learn how to weather conflict to stay in relationship (attachment), find what you’re good at and pursue mastery in it (attachment). I was like a bottomless pit of caring, at that point in my life, and I felt like my dad’s religion was telling me to care less.

I don’t remember exactly what he said to clear up my misread on the nature of non-attachment, but I know it was more about control than care. Non-attachment, for my dad, was a practice in understanding that his anxiety was a reflection of his body’s misunderstanding that he somehow had more control than he did. As a little boy, his mom had given him too much information and too much responsibility, and he had translated this into a delusion of control. He spent decades on the cushion, trying to unlearn that little boy lesson, not particularly successfully.

My dad’s anxiety was often very palpable to me. It would show up most acutely when we were headed out on a big vacation, and he needed to get to the airport hours in advance, after packing and re-packing, making list after list after list. It also peaked around bad weather—the snowstorms of Colorado, and then New Mexico where he lived for awhile, would throw his emotions into a blizzard. Rather than cozy up and surrender to the snow, he would panic about the shoveling and the duration and the shift in schedule. I remember it at Christmas. I remember it when a big case was reaching some kind of inflection point (he was a bankruptcy lawyer). I remember it as one of the pillars of his personality. Another was his unparalleled kindness, demonstrated in his ability to listen so deeply and laugh so easily and wholeheartedly; if you wanted to feel brilliant or hilarious, all my friends knew, my dad was the guy to talk to.

Now my dad has dementia and among so many losses he has experienced—no longer able to drive, no longer able to operate an iPhone or a computer, no longer able to access his laugh at the timbre and depth that he once did—one loss has been magnificent: anxiety. His anxiety has vanished.

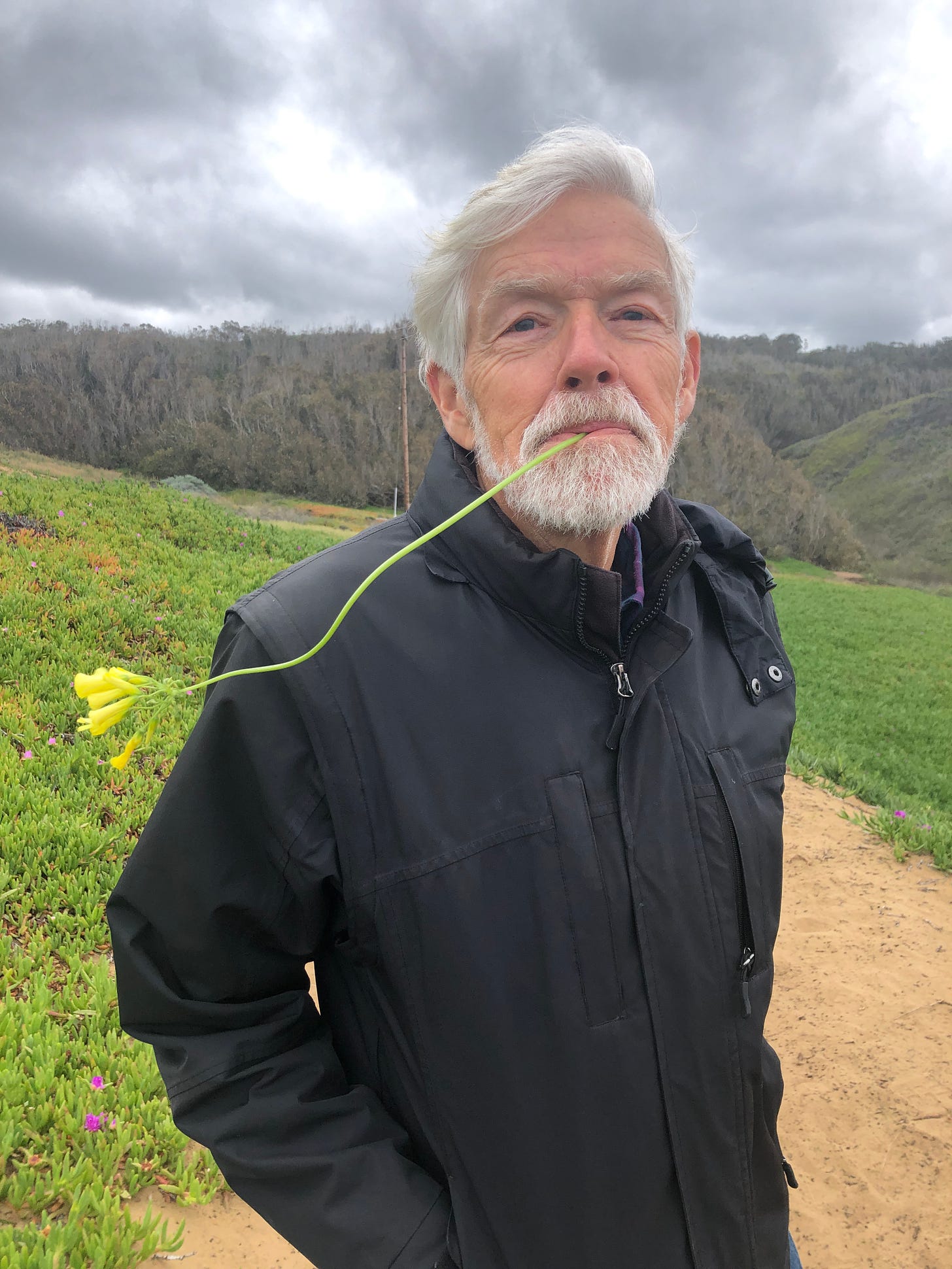

There was a moment, as the disease was progressing, when his anxiety was even more palpable than ever. This season was a painful in-between—his mind worked well enough for him to track the ways in which it was failing. But as things got even worse for him, functionally-speaking, things got way better for him, emotionally-speaking. When bad weather blows through, he has no particular relationship to it; it just blows through. He doesn’t travel much these days, but if he does, as long as my mom is there to manage the ups and downs, he’s along for the ride. Christmas doesn’t bring back childhood memories. The ego ride of work is long gone. His life it largely composed of what is right in front of him—the comfort of his morning granola, a puzzle piece that finally clicks into place, my beautiful mom holding his hand as they walk along a familiar beach and notice what they notice.

The fact that my dad’s anxiety is not, in fact, definitional to him has been the most beautiful gift of this painful moment…and also the most destabalizing realization. It throws me right back into the minivan, wrestling with the concept of non-attachment with him on the way to King Soopers. So much of our lives are spent pinning things down—our personalities, our gifts, our astrological and enneagram types, our style, our preferences…it goes on and on.

We also spend a lot of energy pinning one another down. I watch my kids like a hawk, fitting their behaviors and joys and disappointments into schemas. Stella is the extroverted, resilient one. Maya is the introverted, sensitive one. The truth is, I find a lot of joy in it—the witness and the typing and the evolving nuances that I think I’m grasping about who they are. I have found sacred meaning in feeling like they were born with this essence that has never changed and will never change, something that has nothing to do with me or my parenting, but is just the miracle of how they are made.

But what if it’s all a delusion? What if we spend all this time defining and seeking to understand something permanent and solid about who we are when much more of it than we realize is actually temporary and liquid? What is a self?

I, too, am anxious. Or so I’ve thought. Maybe I am only experiencing anxiety in this version of myself, which is only one possible version that will inevitably shift. What else do I consider core to who I am that is actually unreliable? What else am I attached to about who my kids are that could transmogrify at any moment (and probably an easier time of it if I wasn’t setting it in proverbial stone)?

It puts everything I know to be true about the self in flux. It resurfaces so many conversations he and I have had over the years about suffering and attachment. At the most extreme, it makes me feel like I don’t really know anything about anything. But there is one thing I know: I’m so happy my dad has relief from his lifelong anxiety. What a massive gift.

The other day my dad and I were on our neighborhood walk and I said, “Mom says you’ve been going to a meditation class on Tuesday nights, huh?”

He looked at me blankly—a look I now know well, which means he’s searching his broken brain for the words I’ve just used and landing on nothing useful. “I think it’s online. On zoom. That doesn’t ring a bell?” I say, trying to jog his memory with some context.

Still nothing registers. “Do you remember what meditation is?” I ask him.

He shakes his head no. This man, who meditated daily for at least four decades, no longer remembers what it is. My gut feels a now familiar punch. “Ah, that’s interesting. You’ve done it for so many years, Dad. It’s where you try to clear your mind. A Buddhist practice,” I explain, trying to keep the grief out of my voice.

“Sounds hard,” he says with a breezy tone.

“Yeah, I think so,” I said, laughing a little with him. “You got pretty good at it, I think.”

“Did I?” he said, wide eyed, and smiled at me with Buddha-like equanimity.

Oh, Courtney. [SIGH] Your deep love for your dad is so palpable. What a gift to feel it and your sharing of it. Thank you.

Maybe it's because when my marriage ended it felt like I fell off the edge of the known universe, and the dozen years since have felt like a repetitive releasing of so much that I thought I knew about myself and the world and many of the people around me. Maybe it's being on the far side of my son's transition and my younger kid's coming out as non-binary, both of which just kind of blew my mind. Not because I had any opposition, but just because I never suspected prior and had always prided myself on how well I knew my kids. (Pride goeth, as they say.) And now I'm (recently) 52, my mom is 83, my oldest brother is 62 and we're finally easing into a new phase of relationship to each other, which involves letting go of many of our presumptions about who each other are and how this life is going to go. Maybe it's all of those things, but I'm beginning to feel like the fluidity of self, the sheer mystery of who we all are, or become, over the course of an entire life, is kind of a miraculous gift. Anything is possible (Gah!), but also anything is possible (Wow!).

Otherwise, how would we ever experience forgiveness or revelation or surprise? To get those things we have to leave the door open to unknowing, risk, confusion, and uncertainty, which the teenager in me resists heartily, thinking it's sort of a crap-ass bargain. But current me realizes what a gift it has been to learn to love with open hands, so okay. I'll take it, all of it.

This extraordinary insight into dementia and Buddhism makes it imperative that Courtney consider writing a book on it. We've mentioned before the Buddhist writings of Thich Nhat Hanh and the Dalai Lama, who offer deep analyses of the "self" but don't relate it to Alzheimer's specifically. Courtney is fortunate to have the theoretical background, remarkable skill as a writer, and the most intimate lifelong relationship with one suffering from this dreaded disease.

Buddhist philosophy and practice definitely enhances this compelling story.

Finally, Courtney is fortunate to have her father able to speak coherently , (unlike my brother and also a close friend, who became unintelligible)so it's important to use this time wisely. From my perspective of 86 years, I see this as an opportunity to give us all both solace and assistance. We need to read many more personal narratives by brilliant authors like Courtney, to help us cope in this monumental struggle. DD