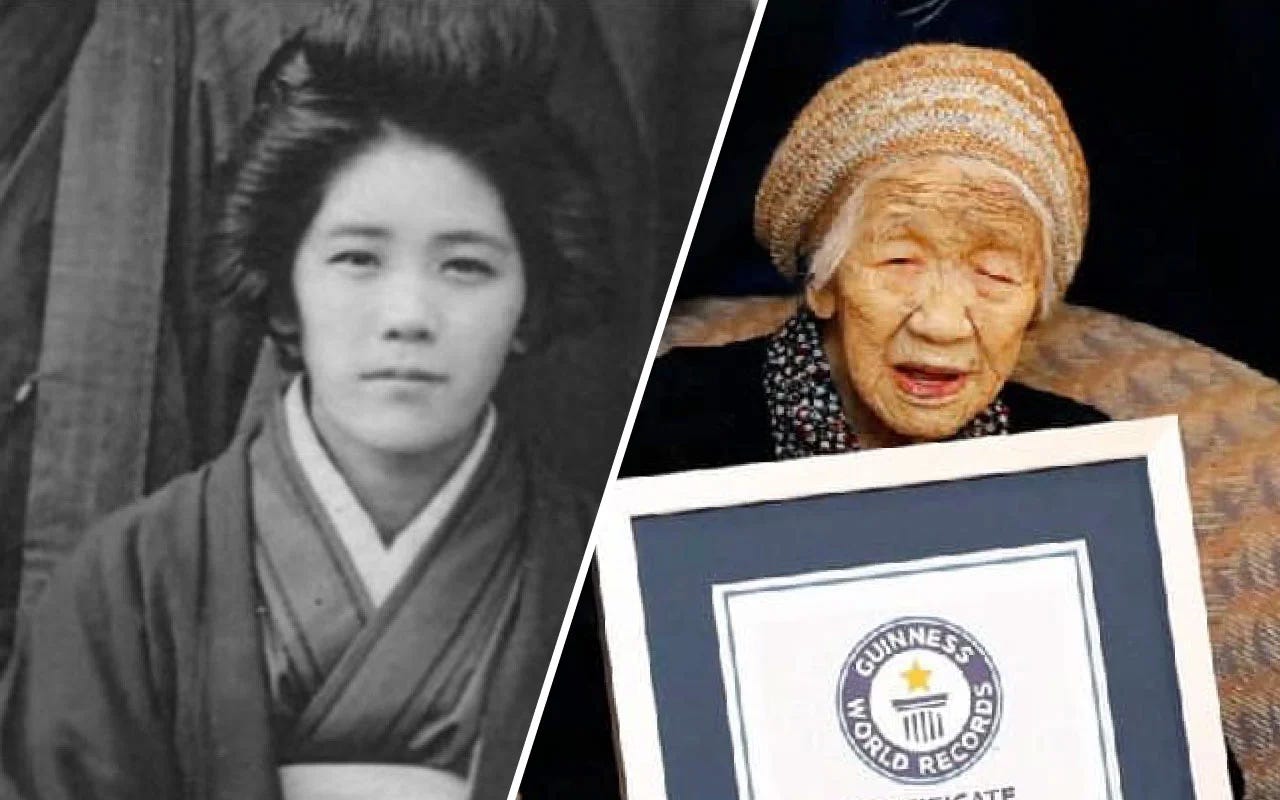

The oldest person in the world died last week. Her name was Kane Tanaka and she was 119 years old.

She was born in 1903, the year that the first silent film, The Great Train Robbery, debuted.

The Irish Times reports that she liked chocolate and fizzy drinks and was still waking up early in the morning to learn math.

I’m captivated by this—not because I am obsessed with living forever. In fact, while I love Ms. Tanaka’s zest for life, I don’t envy her. I have never forgotten a conversation I had with my husband’s grandmother, who told me that—at 92—she had watched most of her friends die. “Does it get any easier?” I asked.

“No,” she said solemnly. I loved her for her honesty in that moment.

I don’t want to watch my friends die. I don’t want to contend with a body and all its inevitable woes a century on. I don’t want to live forever.

What captivates me about Ms. Tanaka is all that she has seen. Generations have this paradoxical quality. On the one hand, a generation is often defined quite broadly—chiseled out of a decade plus of the blunt instrument of breaking news and the slow erosion of cultural trends.

For me: the most notable blunt instrument was probably 9/11, when I was 21, living in New York, watching women in business suits, their heels in their hands, arrive on the upper west side seeking safety. It created a before and an after in my consciousness. I remember sitting at a cafe with my then boyfriend wondering if I would ever get to have kids. At 42 and the mother of two, that reaction strikes me as strange and disconnected from what was actually going on, but I suppose I didn’t know that then. I just knew that one day the world felt marginally predictable and safe (a privilege of demographic and perspective, of course) and the next it did not.

Culturally, hip hop was king—what I now think of as a very complex legacy of my teens and twenties. The soundtrack to my youth was a music that actually had very little to do with my daily reality, a borrowed emotionality, a bumping hunger for something more honest than what the mostly White neighborhood I lived in offered.

The paradox is this: while we overlap with so many people in this life (we each sort of occupy a 200-year present, if you think about the span of our families) we also occupy a super specific sensibility based on the moment we were born. By the time Ms. Tanaka died, she probably knew almost no one who could bond over what it was like to see the first movie with sound. On the other hand, she lived through covid, learned the phrase “social distancing,” and watched the world shut down—just like my 5-year-old.

Life is such a wild layering on and on and on. My 9/11 consciousness is now buried under my Obama consciousness and my Trump consciousness and my pandemic consciousness. Hip hop is in my bones as is Dirty Dancing and feminist blogs and Ocean Vuong and Better Things. Think of all the tectonic plates that made up Ms. Tanaka’s perception—the global cataclysms, the before-and-afters, the inventions, the music, the movies, the math.

We have geologic psyches. I have a hunch that most of us barely understand what has shaped our own consciousness, so is it any wonder that we sometimes find one another’s motivations and expectations opaque when dealing across generations? Is it any wonder that some of us want to make small, meaningful shifts and others want to burn it all down? Is it any wonder that some of us prize care and others freedom (not that they must be diametrically opposed)?

Yes, our families of origin play a massive role in how we see the world, what we want from it, as do our demographic and religious backgrounds, the kinds of bodies we are born into, the sort of temperaments we are born with. But it seems pretty magical to me that there are people like me, born on the last hour of the last day of the last year of the 70s (or thereabouts), who have been adding all these layers-in-common.

I find excavating them both sad and delicious, like hearing a collective story of the human condition at the most epic of scales. It makes me feel less alone and also part of history. It reminds me of how we endure—headline after headline, song after song…until we don’t.

My nephew is turning nine today (happy birthday Atty, my love!) and I got him a kit from National Geographic where you can break apart ten geodes. Ms. Tanaka’s soul is a bit like that—in my mind—this ancient, rocky outside that, when cracked open, would reveal luminescent crystals, organically grown over years and years of alchemy between her inner world and the one outside of it. RIP Ms. Tanaka. I raise a fizzy drink in your honor today.

May we not live quite so long, but certainly live so joyfully.

A fascinating read on our generational consciousness - thank you. So much to ponder here. I loved your aside about others born at exactly the same moment as you who still have different experiences of the same lifespan. My spouse and I were born on the same day, nine hours apart, and you helped me give language to my occasional bafflement at wondering how he didn't experience the same event that shaped my consciousness. Or even when we lived through the same generational crisis, we can still have vastly different experiences. I was studying abroad in Paris on 9/11, for example, and he was in college in Indiana. So our conversations about that day and the era it shaped are completely different. Each of us have our own tectonic plates, so no wonder our shifts are never precisely the same.

My maternal grandmother lived to 94 and was walking at the mall every day for an hour until the day she died. I have always said that I want to be like Grandma Rose and live as much living as I can in the years I have left in this world. Ms. Tanaka is another example of living fully and grabbing wonder and bliss wherever you can in the midst of so much ugliness. What a great role model for us all! Thank you for holding her up in this light.