Cracking the code on liberated pleasure

5 questions for sex writer, feminist daughter, and new mother, Nona Willis Aronowitz

I never really went to journalism school. Instead, I want to a school at NYU called Gallatin where you can design your own master’s program. Mine was called “writing and social change” (yes, I was very much who I am now back then, too) and I took classes in grant writing, oral history, feminist art, teaching, and, indeed journalism. One of the few journalism classes I took was called “Reporting Social Worlds,” a dream class, not just because of the subject matter, but because of the professor, a second-wave feminist who had written all these amazing things that I looked up to about music and sex and ambition.

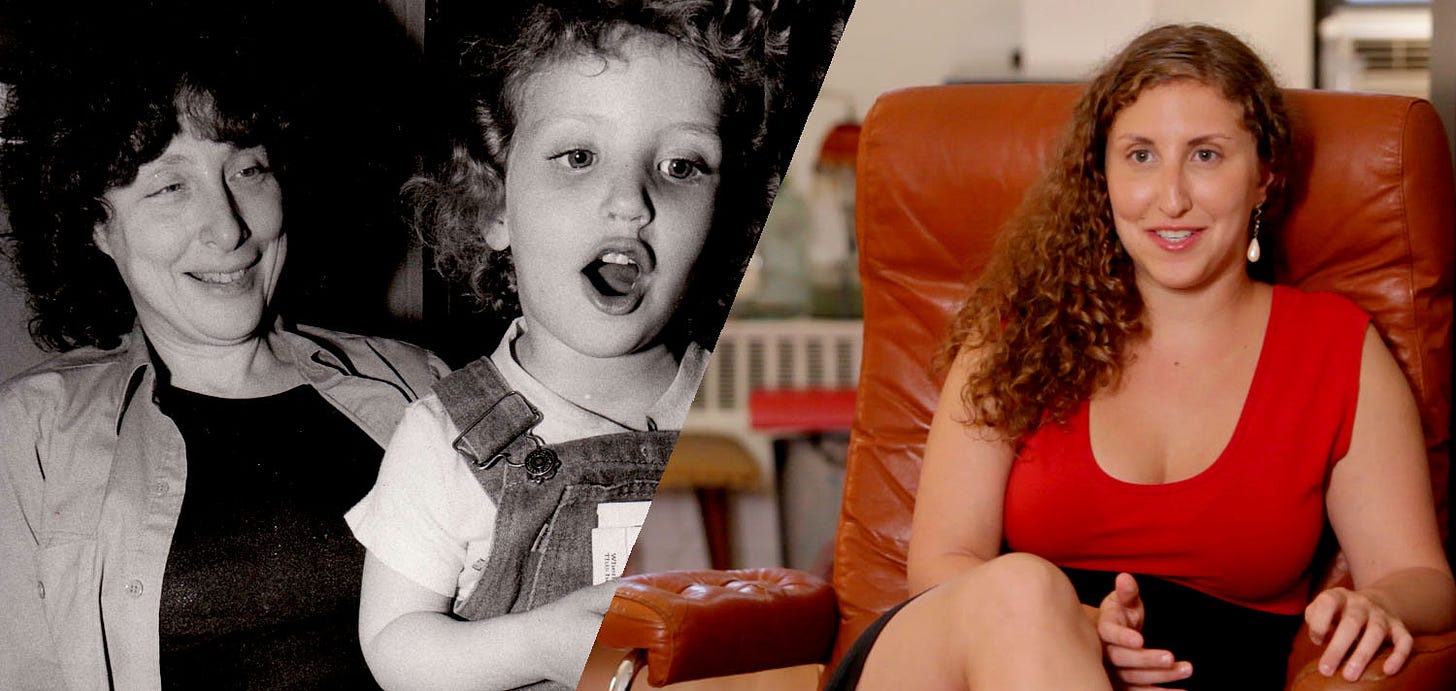

Her name was Ellen Willis, and she intimidated the hell out of me. She had a big mane of gray frizzy hair that fell over her face, and she had us read Joan Didion and notice that details were the secret sauce of any good piece, that we must write EVERYTHING down and then pick the exact, perfect detail out of mountains of reporting. I wanted to impress her so much I could taste it. And I did, a little bit, but also not that much. Which is sort of how Ellen felt to me—you had to really earn a compliment.

Then I met her daughter, who was about to embark on a big road trip across America with her best friend and report on the new frontier of young feminism. We sat in a coffee shop in the west village and I marveled at how such an inscrutable woman had produced such an exuberant daughter. Nona was kind, crass, and clearly brilliant. I loved how different they were in temperament and how alike in interests and palpable liberation. They were both, in different generations, in different ways, so free.

Nona and I have kept in touch over the years and I’ve loved watching her career unfold. Ellen sadly died in 2006. It was a huge loss, and yet Nona has kept her work alive (literally through writing about it, compiling collections etc.) and through her own gorgeous legacy. Nona has a new book and a new baby out just weeks apart. I wanted to talk to her a bit about both.

Without further ado, meet Nona…

Courtney Martin: A lot of Bad Sex: Truth, Pleasure, and an Unfinished Revolution is about what you describe as “reconciling personal desire with political conviction.” Turns out, that’s not an easy reconciliation. Why do we have such trouble aligning what happens in our bedrooms with our political values?

Nona Willis: Aronowitz: The short answer is that political values are often clear-cut and logical—they kind of have to be, because the most effective activism often demands simplicity and moral clarity—but that’s just not how humans are. They are under the spell of a constellation of competing influences and life circumstances that muck up this moral clarity. They’re also socialized in the world that exists, rather than the world they wish for. So ideology has never been a reliable way to steer our emotional needs, but this appears to be particularly true when it comes to sex, because our sexual desires are so slippery and subconscious and surprising. (Those same qualities, by the way, are why I find sexuality so fascinating to research!) Romantic desires are also famously destabilizing; anyone who’s been in love knows that it can literally feel like a mental illness.

And then there’s the special case of heterosexual or bisexual women, who are pretty much the only oppressed people who deeply want to love and fuck and build lives with their oppressors. So you can have an epiphany about how horrible and destructive patriarchy is, but still fall under the influence of the highly volatile forces of libido and love and therefore make the “wrong” political decision. All of this can make us feel very out of control, but it’s a reality that any feminist—particularly one who has sex with men—will at some point contend with. I think it helps to acknowledge that regardless of what future you’re fighting for, you’re still a human living in the present who was also a child in the past. Your desires aren’t living in a hypothetical utopia. So they’re going to be a mess of contradictions.

Your mom was a prolific writer about some of the same issues you explore in your book. Do you feel like this subject matter is sort of an honorable inheritance or did you ever rebel against the inevitability of becoming a feminist writer who is interested in these particular questions?

Both! On one hand, I’m proud of the work she did and do feel honored to pick up where she left off. Writing about these questions feels very natural to me. But I’ve definitely gone out of my way during various points in my life to do things differently than my mom: to learn how to do investigative reporting rather than long literary essays, for instance, or experiment with other beats as a journalist besides gender and sexuality. I went through stretches of my career where I focused on the economy or education or film. Yet all roads kept leading to these essential questions of how we love and how we structure our families and how we experience pleasure. I have definitely felt sheepish and unoriginal about following in the footsteps of my mom (and my dad, a professor who also wrote books). Especially because I sometimes feel like I’m one of those people who feels like I’m a writer, not because I love it, but simply because I don’t have any other skills. It feels kinda out of my hands!

You write about the ways in which genuine or organic sexuality, unfettered by societal expectations, is elusive, if not impossible. But we can’t give up on the lifetime project of getting to know our own desires and parsing them out from how we’ve been conditioned, right? If someone is reading your book, and wanting to get more in touch with their own desires, what do you suggest they do next?

We definitely shouldn’t give up! It’s not like it’s impossible to have moments or phases where we feel completely sexually satisfied. I’ve certainly had these times—some of which show up in the book—where I’ve felt extremely euphoric and fulfilled, like I’ve cracked the code to my own pleasure. It’s just that a) those desires and that code are seldom static and very subject to change, and b) even those wonderful times will be somewhat wrapped up in our social conditioning, because our sexuality can never be context-free.

My suggestion is to surrender to this continual change and surprise, to leave yourself open to exploring but not feel pressure to explore. Obligatory exploring does not feel good! Try not to feel guilty about a desire that aligns with or reflects the dominant culture, as long as you have truly and actively determined that it makes you happy. And don’t feel discouraged if your desires completely shift during the phases of your life; even a nosedive in libido can be an interesting experience. (As I write this seven weeks postpartum, I can tell you that I’m both hornier than I expected to be, but also a million miles away from the woman I write about in this book. It’s just impossible to predict the twists and turns of our desires, and that’s actually really cool!)

You just gave birth and became a mother! Anything you would have done differently in the writing of this book with that new, very corporeal experience?

I think it’s a little too soon to know what my sexuality will look like as a mother; I've just barely begun to reckon with this new identity and what it’ll do to my desires. I can say that the experience of pregnancy and birth were completely radicalizing, and I wish I could have added some of those insights to the chapter I wrote about abortion, especially given the recent reversal of Roe. I was taken aback by how pregnancy hijacks not just your previous sense of your sexuality, but every single millimeter of your body, your brain, your emotional state, your ability to work and move, in horrific and unexpected ways.

And birth—holy shit. I had a relatively uneventful and intervention-free birth so it wasn’t traumatic or anything, but it was extremely painful and one of the hardest 24 hours of my life! This was a wanted and planned pregnancy but after all that, I cannot fucking imagine being forced into that experience.

Your mom died many years ago, but you have been accompanied by her words ever since. If you could commission her to write a book from the beyond, what would it be about?

I love this question! She was a self-proclaimed “leftist libertarian” (an illegible identity nowadays I feel like), so I’d love to read her perspective on “cancel culture.” Her spidey sense went off whenever a group—left or right—started dictating other people's behavior, like when feminists started wanting to ban porn. But she was also very wary of moral panics, especially when they benefited the right wing’s agenda. I have a feeling she would find a way to pinpoint the very real chilling effect certain strains of the censorious left has on public debate, without aligning herself with the center-left crowd that thinks “cancel culture” is the worst thing to ever happen to America. But I’m actually not quite sure what she would say, or whether I’d agree with it...precisely why I’d want to read it!

Order Nona’s book here or grab it at your local bookstore. It’s out this week!

In honor of Nona’s labor (a many-layered word this time around) we have donated to The Brigid Alliance, a referral-based service that provides travel, food, lodging, child care and other logistical support for people seeking abortions.

I remember asking my midwife at my 24-hr check-up post-partum how long I had to wait to have sex because I was craving the chance to inhabit my body again sensually. She said she'd never been asked that question before. She encouraged me to wait six weeks. I think I made it for four.