If you’re free at 9:30am PST and interested in care and the economy, RSVP for this online conversation I’ll be having with Heather Boushey, one of the smartest economic minds in the nation and a member of the Biden administration.

SPECIAL OPPORTUNITY: Join us for an Examined Family online book club meeting on Needy by Mara Glatzel on June 30th at 9am PST / 12pm EST! RSVP here. Buy the book here. Mara will join us! We can’t wait to hear your thoughts, questions, and experiments with reclaiming your sovereignty. (We’ll probably cap it around 100 people, so get your spot before they run out.)

Examined Family is written by a flesh-and-blood person, not a moody ChatBot. If you subscribe already, you probably guessed that. And thank you! If you don’t, now’s a great time.

As I’ve been going about my work the last couple of months, I’ve been asking myself an extra question: could AI have done this?

(If you don’t know a lot about artificial intelligence, I get it. It can be intimidating. Here is some stuff I’ve been reading/watching/listening to on it: this, this, and this, for starters.)

In late April, I landed in Cincinnati, drove the 45 minutes to Middletown, past the touchdown Jesus statue (and boy, is that a story!), and sat down at O’Farrell’s with Pastor Scotty Robertson, noticing his flip flops, the waiter’s long, manicured nails, the amazing small of the blackberry cobbler, warm with vanilla ice cream melting all over it. I had a set of questions for Pastor Scotty, but I mostly forgot about them once we go deep in a conversation I never could have anticipated about structural racism and truth and love.

AI could not have done that. It could not have smelled the blackberry cobbler or noticed the human essence. It may have been able to redirect a conversation, but not with my particular set of instincts, experiences, and attention to surprise and subtle human cues.

It couldn’t have written the piece I wrote, particularly picking a seemingly subtle moment during a school board meeting I watched that became the perfect metaphor as I closed the piece. (For more on the reporting and writing of that piece, check this out.)

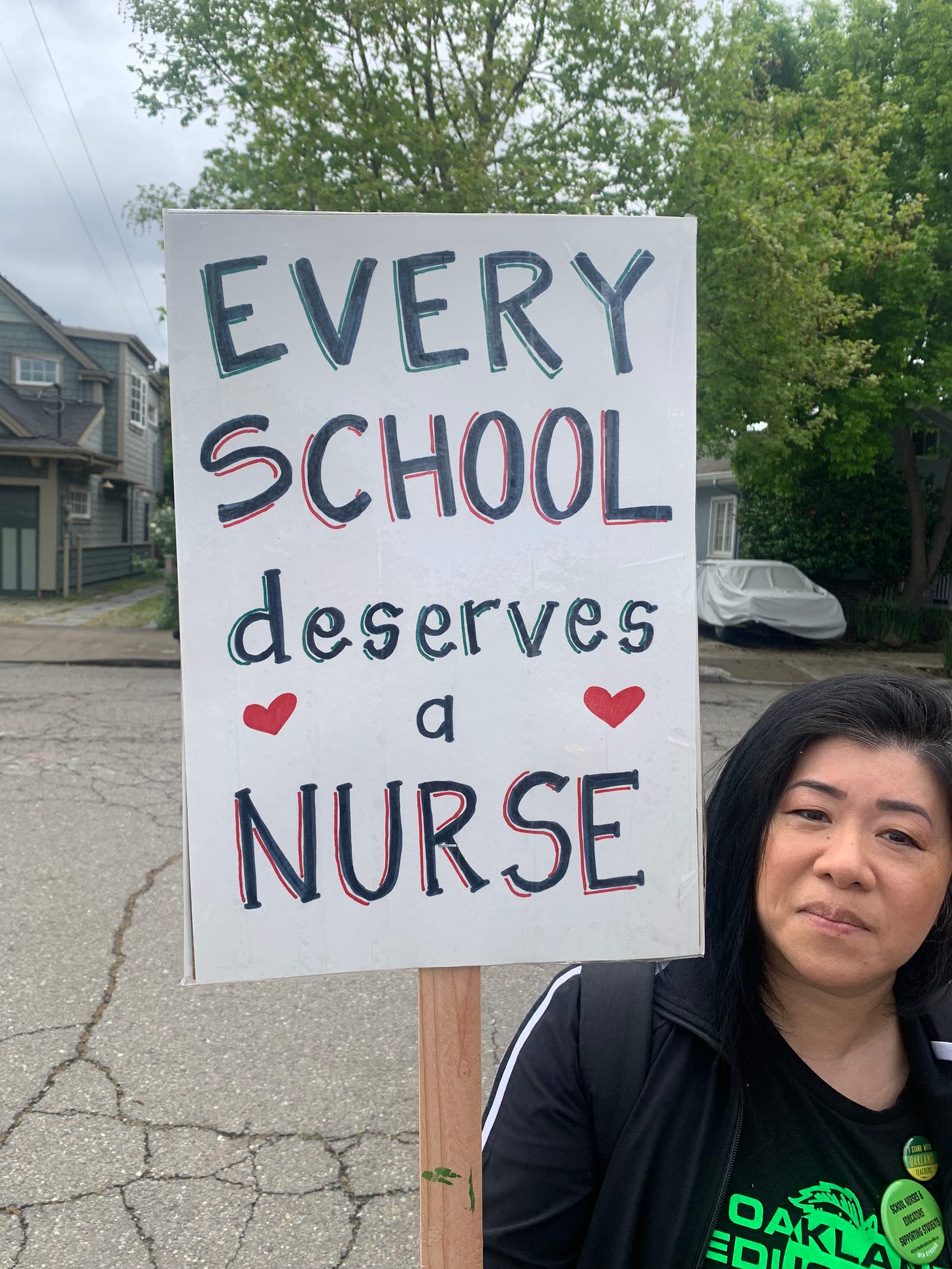

This month, I’ve been pouring over a story on the rise of “common good bargaining” for Vox. I’ve been interviewing a wide variety of national and local Oakland experts (teachers, organizers, advocates, historians, caregivers). I’ve been trying to make sense of this approach to teacher bargaining (not exactly new, as it turns out, but being resurrected after a narrower moment in union bargaining).

AI probably could have done a lot of the “fact finding” that I did for this story—the more traditional parts of the reporting where I am looking at the history of teacher’s unions and learning who is involved in this new wave of common good bargaining etc.

AI couldn’t do the live rapport-building and interviewing, at least not yet (there are companies that are using AI to do preliminary customer service interactions, for example, with success). I’ve been deliberating about which quotations to use, which possibilities to acknowledge, which limitations to include. There is a lot of power in those decisions—could AI make them better, in some sense, because they’re not as clouded as I am by my own personal connection to the issue (parent of two public school kids, professional enthusiast about teachers, obsessed with inequity in our schools) or would AI make them worse because of the lack of personal connection? I have no idea. What might the measure of an answer to that question be? I also have no idea. The article hasn’t been published yet, but I hope that when it is, it will be useful and feel nuanced and true to a wide range of people.

What about this very newsletter, you might be thinking? Could Courtney deploy an AI to write newsletters for the next two months while she is on sabbatical? Well, the answer is yes and no. I asked ChatGPT to write a 100-word paragraph in the voice of Courtney E. Martin, and this is what it gave me:

In the ever-evolving landscape of family dynamics, the examination of our experiences takes on renewed significance. It is through honest reflection and intentional inquiry that we uncover the untold stories, the nuanced complexities, and the shared vulnerabilities that shape our family lives. As the author of Examined Family, I invite you to join me in this journey of exploration, as we delve into the intricacies of parenting, partnership, and personal growth. Together, we will navigate the joys and challenges of raising resilient children, forging deep connections, and fostering a sense of purpose within the ever-changing tapestry of family life. Let us embrace the messy, the unexpected, and the transformative as we seek to create a more compassionate and connected world, one family at a time.

What do you think? To my mind, that’s college-age Courtney. She’s endearing, but not exactly worldly. Her language can be empty if she’s not careful about cliche. She’s asking the right questions, interested in the right topics, but isn’t writing about them in a particularly fresh way. (I’m also slightly freaked out, honestly, because this was generated in like 30 seconds and does, legit, sound like me. Maybe we need a new word for the emotion that AI causes when it does something you thought was uniquely you in an almost accurate way in 10 seconds?)

And that brings me to a few larger instincts about AI’s role in the world, at least the writer’s world. I do think that AI is going to transform all of our lives. It’s not overblown to relate to this as the next technological leap forward—as big, if not bigger, than the internet itself. And I do believe that if it can be harnessed for good, that will mean reducing the administrative burden, also known as cognitive load, on so many people—particularly caregivers, those who have historically had to navigate bureaucratic government systems etc.

For writers, it means getting quicker answers about more things, “cheating” on structure (ChatGPT doesn’t always fill things out well, but often seems to have good instincts about the way to organize them logically), and never facing a truly blank page again. But I don’t think it has to mean the end of our profession; readers will always want ingenious, quirky, metaphor-filled writing…writing born of experience and sensory observation, not algorithms…writing that feels full of a distinctly human feeling. At least so far, AI can’t quite generate that.

Perhaps the paradigm shift brought on by AI will bring us even more deeply intro our bodies (AI can’t detangle my daughter’s hair or tell her what it felt like when I first looked into her eyes when she was born). Perhaps it will resurrect an appreciation for art made by humans—forcing us to figure out new economic models and systems of celebration, fandom, and acknowledgment. Maybe we will learn to ask even better questions when we are with our people. Wouldn’t that all be so beautiful?

Lest I sound naive, trust me, I am also freaked out by the very real dangers of AI. On that, I think the Center for Humane Technology is really instructive. What are your thoughts about this quickly moving technology and the impact it could have on all of our lives? If you haven’t played around with ChatGPT yet, I highly recommend it. It’s hard to get a feel for how this technology might change things if you don’t have a hands-on experience of it.

Fwiw what the AI wrote didn’t sound like you to me at all

I've read a bit about the benefits of Chat GPT, e.g., it can help K12 teachers differentiate reading passages for students. I'm sooooo not sold though because as a former educator and recent but former college adjunct professor, I see the dangers. For one, as you pointed out, something is missing from the Chat GPT-generated "Courtney" paragraph, and to me that something feels like the writer's soul and humanity.