What do you say when someone tells you that they have cancer? What if they say that their kid has cancer, or a drug addiction, or a mental illness? What if they tell you that their mom has Alzheimer’s or their sister died unexpectedly?

If you’re not sure what you say, and you also suspect it might not be so wise, you’re not alone. Americans, generally speaking, don’t seem all that great at acknowledging that we have frail and precious bodies that break, sometimes irreparably so, and further, that we love people (our parents, our best friends, our kids) that also have these kinds of bodies. It’s terrifying, first of all, and made more terrifying by the fact that we have so few rituals—containers if you will—to hold the terror, either individually or collectively.

Part of why we love a casserole or the modern day version—the meal train and then the casserole, let’s call it casserole 2.0—is because it makes us feel like we have acknowledged someone’s bad fortune and can move on with the delusion that our bodies will never break and that the people we love will march on into eternity unscathed. Don’t get me wrong: casserole 2.0 has a certain nourishing quality. I remember the homemade lasagna that my friend Carrie dropped by after my first baby was born so well it’s bizarre; that was ten years ago. Of course it’s nice not to have to think about cooking when you’re nauseous from chemo meds. Of course food is an expression of love. Keep cooking those casseroles…

And we must not fool ourselves that casserole 2.0 is enough. Or that all of our people’s pain can be seen, identified, and project managed in a finite amount of time or solved through food. We must try to be braver and truer and look our people in the face and say, “That fucking sucks. Tell me more.”

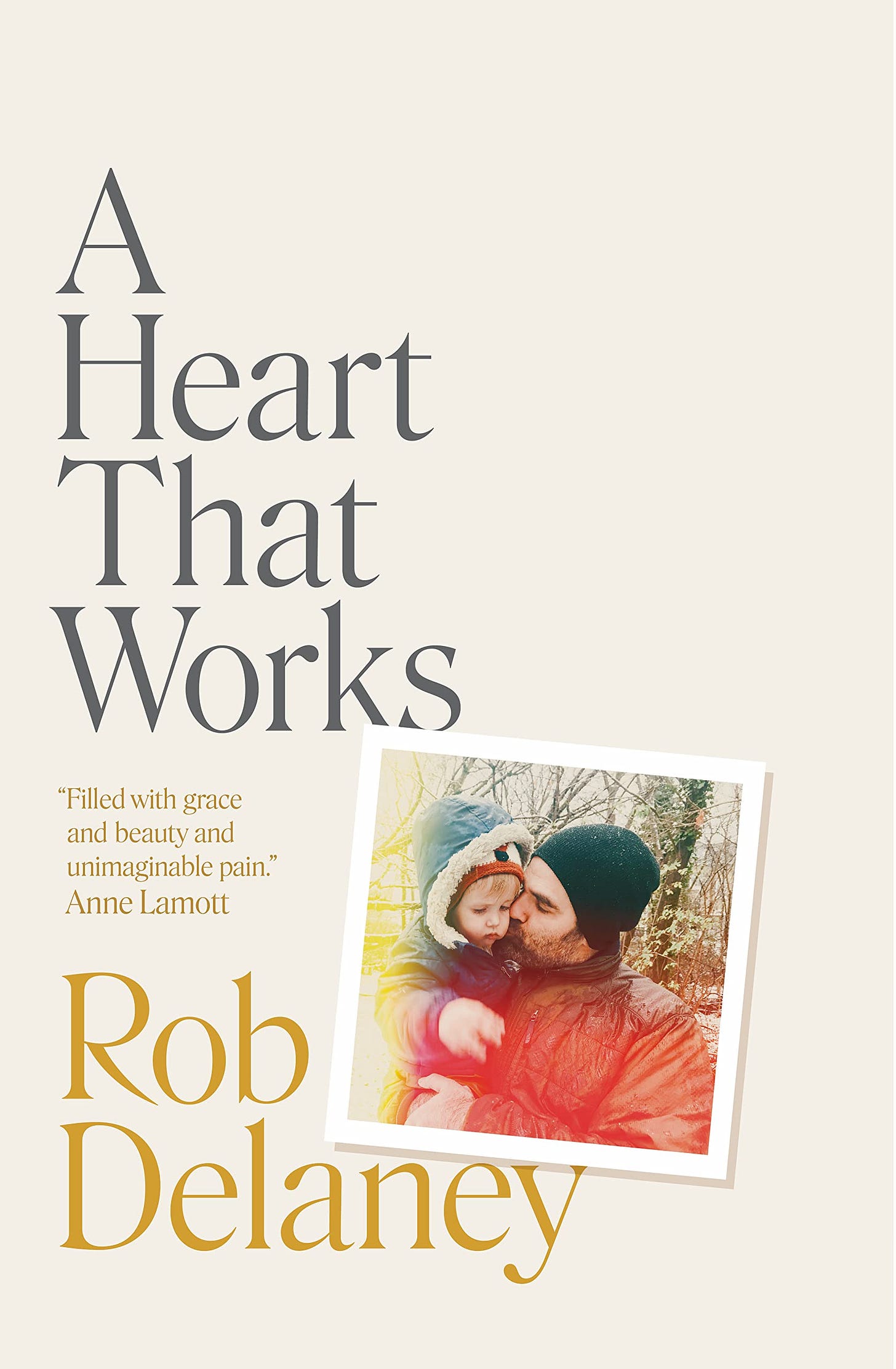

I’ve been thinking about this after reading Rob Delaney’s funny, sacred, sweet memoir, A Heart That Works, about his 3-year-old son dying of cancer. It’s named after the Juliana Hatfield quotation: “A heart that hurts is a heart that works.”

I read it in one sitting. I knew I needed to do that, to read it in a place and time where I could dive in knowing it would bring up my own terror about my children’s bodies and their vulnerability. It did. And it was also a profound privilege to witness Delaney’s way of moving through such a horrendous, beautiful experience, and make meaning of it, and offer up that meaning to us—strangers who now get to read about his dead son’s fantastic sense of humor and dedicated, creative nurses. The reader has the unique chance to be reconnected to our ineffable gratitude that our own children are healthy, for now, for now, for now, for now…and that if they ever become not healthy, Delaney has offered a way of surviving.

I’ve wanted to recommend Delaney’s book to people, but also felt reticent. Is it kind to encourage people to read about a three-year-old dying? I guess it depends on what’s going on in their own lives and what their capacity is for being in touch with the vulnerability of our bodies. Some people I’ve mentioned it to, people with healthy children, have cut me off before I can even finish and said, “I can’t. I just can’t.”

I get it, but it also makes me wonder: what are the thresholds beyond which we lose the capacity to witness one another’s pain?

Whether it’s reading about it in a book, or just responding to the truth in live time, there are certain kinds of pain that a lot of us seem very resistant to fully acknowledging, as if that pain is contagious, as if the flame of it is too hot, as if it forces us to look at something we are unwilling to look at in our own lives, our own hearts, our own bodies.

I see this from both sides. I don’t feel great at showing up for people whose lives get obliterated by illness, but I’m getting more and more practice lately and I’m doing my best to notice my own unhelpful tendencies while “helping.” I’m noticing how I have that early peak of empathy and energy for reaching out and taking action for a person, and then it peters out while they’re still going through the thing they’re going through. So I’m working on my stamina. I’m noticing how when I don’t know what question to ask, I sometimes don’t ask any question at all. So I’m working on not knowing and just reaching out anyway. I’m noticing that, sometimes, if it’s been long enough, I let guilt keep me quiet for even longer. So I’m remembering it’s not about me, it’s about them, and they get to be the judge of whether I’m a shitty friend or just another bozo on the bus trying to show up imperfectly.

I also have been experiencing what it’s like to be on the other side of the equation. Someone I love very much has dementia. When I tell people, they generally respond pretty badly. Some people don’t really acknowledge it at all, as if the chiller they act about it, the more comforted I will be. Some people immediately relate in a way that is totally irritating: “Wow, I didn’t realize that! You know I was noticing my aunt was forgetting her keys a lot on our last visit home.” This is not about keys. This is about someone’s way of being themselves in the world transforming and all the people around them trying to figure out how to stay in loving relationship. Some people ask a lot of technical questions that I don’t have the answers for—how long has it been going on? how far along is it? what kind is it? It feels like they’re planning to write a memo later—for who or what purpose I have no idea.

What feels good is when people respond with genuine emotional resonance and ask me how I’m doing with it all. Simple stuff like “Ugh, that sounds so hard. What’s it like for you?” Or, “How is your grief these days?” If I don’t feel like talking about it, I can tell them that. Truth is, I mostly don’t feel like talking about it (even writing this is hard), but sometimes I talk anyway; not because I feel socially obligated, but because I know it will help me bear this thing if I can say it out loud to the people who love me.

My hunch is that there are certain illnesses, like dementia, and certain ages/stages, like kids with cancer, or the sudden death of a younger parent or partner, that we struggle to face in friends’ lives because we are subconsciously unwilling to admit they are an ongoing possibility in our own. We essentially clench our eyes shut tight, put our fingers in our ears, and hum in hopes that it will go away. It’s like our silence and awkwardness are ways of praying to a god we may or may not even believe in, “Please not me not us not me not us not me not us.” That prayer, then, makes us feel subconsciously ashamed. We know that shouldn’t be focusing on our own fears; we should be responding to someone else’s pain. But we don’t know how. Shame shuts us down further.

You know what? It is SCARY. It’s scary to love people who could lose their minds and/or have bodies riddled with deadly cancers. It’s SCARY being human and loving people who might get in car accidents. But you don’t have to beat yourself up about being scared. You can comfort yourself first—dang, this is scaring me, being so close to this thing. That’s okay. That’s understandable. And then get on to the business of showing up for the person who is actually experiencing it right now. Get curious about what you don’t know about what it’s like to go through this particular thing for this particular person. And inevitably you will be blessed with wisdom beyond what anyone who is lucky enough to not go through that thing could offer.

Like this, from Rob Delaney, who says that when people tell him they’re pregnant for the first time, he doesn’t focus on the hard stuff, as most people do (Get ready to never sleep again!), but on the obscenely good stuff:

So you’ll be fine with the difficult parts! You’re already a pro. What you’re NOT ready for is the wonderful parts. NOTHING can prepare you for how amazing this will be. There is no practice for that. There is no warm-up version. You are about to know joy that will blow your fucking mind apart. Happiness before this? HA. HA. Mystery? LOL. Wonder? Fuck off! You are about to see something magical and new that you have no map for! None! This is it. Are you ready for that? Are you? No! No, you’re not! Also, please let me babysit when you’re finally ready to let someone else hold your beautiful little nugget!

In a weird way, the experience he’s writing about could be about illness or death as much as it is about birth. There is no map. There is so much mystery. There is no warm-up or practice. And yes, there is even happiness in the midst of so much sadness. Because nothing in life—not even kid cancer or dementia or so many unspeakable misfortunes—are all one thing. If you don’t ask people open ended questions about terrible things, if you don’t show up again and again, you’ll never get the chance to see how multi-dimensional they are. And this, my friends, is the full-spectrum human experience—laughing at the funeral, crying at the school play, fear and shame and love so big and small at the same time that it never dies.

Related reading: my interview with cancer survivor and interdependence expert Mia Birdsong on showing up for people in acute crisis and a piece I wrote a long time ago about The Dinner Party organization which creates ritual around grief. Also I’m reading the galley of Laurel Braitman’s What Looks Like Bravery and it comes out in March and it’s got all of this written all over it.

Assignment: send a text, call, or show up at someone’s door that you know is going through a thing and say, “How is your grief today?”

I really needed to read this today. Thank you.

After my husband died unexpectedly at 32, there was one person who was most comforting in the immediate aftermath—a coworker who had lost her partner to suicide a few years prior. She sat next to me on my couch and said, "I'm so sorry. I wish I had other words to offer you, but I don't. I'm sorry and this sucks. And I'm here to sit by you as long as you want." We sat in silence for a while, crying. As horrible as that moment was, those words made me feel so much better.

I've always wanted to be that person for other people and I'm not entirely sure that I am. I need to work on my stamina, as you so smartly put it, for being present during difficult moments.

It’s not just America/modernity. In the Old World Indian culture I grew up in there’s plenty of stigma and superstition and people distancing themselves from particular types of vulnerabilities - sometimes from ignorance thinking it literally might be contagious, other times from misogyny or other identity-based prejudice that blames the victim. Yes in other more common circumstances ritual provides a time-tested container and acknowledges grief and vulnerability, like when someone dies or is ill with something widely understood. But when it’s an ill of a different ilk - mental illness or, say, divorce - the customary responses are downright harmful.