“Love is simply the feeling that I am grateful to be here and I am grateful you are here, too, even if you’re on my fucking nerves, which to be honest some of you are.

One impact of a society that gives some people unquestioned right to all the resources and power is that it creates out of those people a population who cannot understand the sheer and simple love of being alive, the love of gratitude, the love of satisfaction and serenity. Everything is too little for them. The world is never enough. There is not enough action. The mere act of being is not meaningful for them. It never can be.

Sometimes I think our society will be forever lost until we are no longer ruled by people who feel this way. Or until they, too, lose enough to be grateful for the mere fact of being. That may be painful. That may be right.”

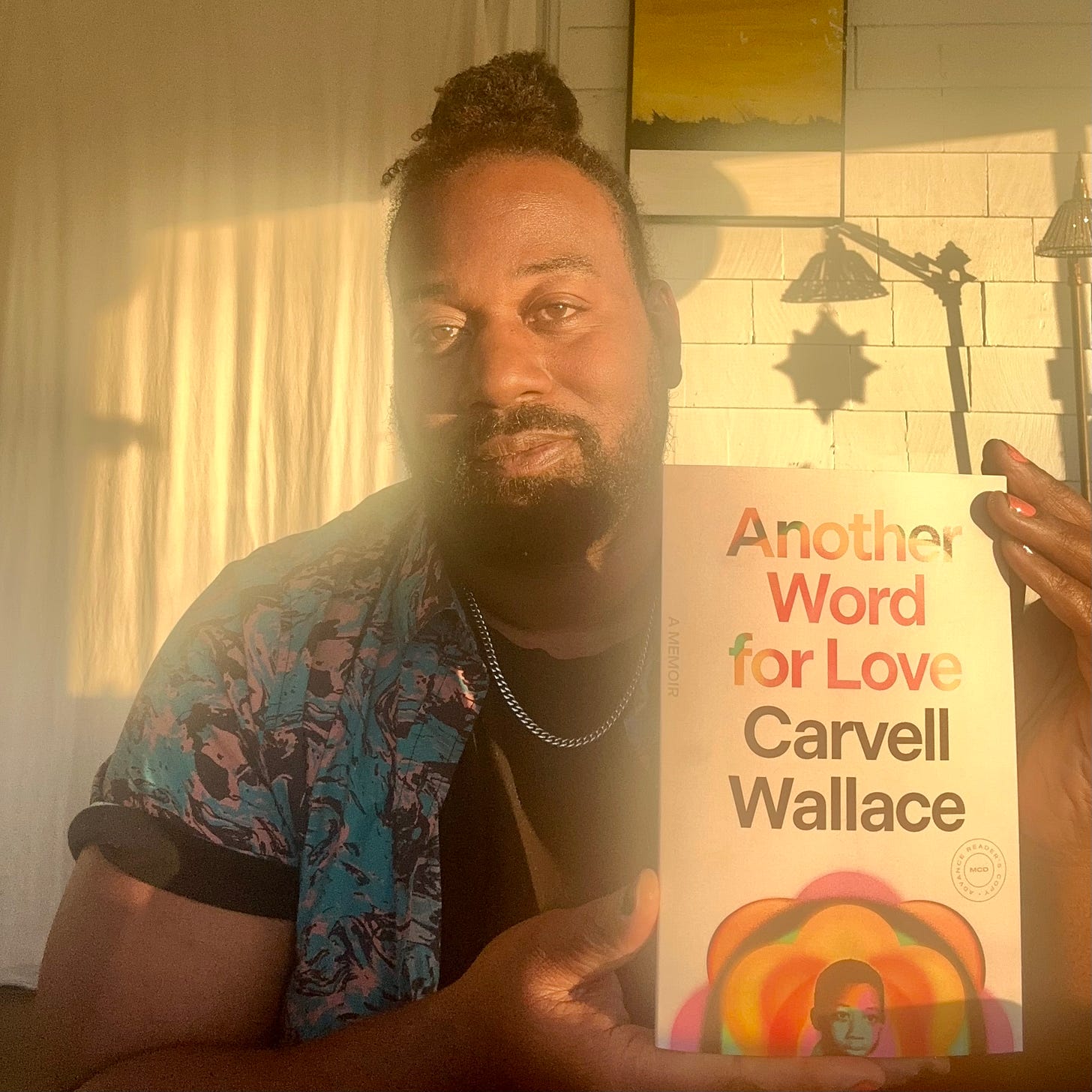

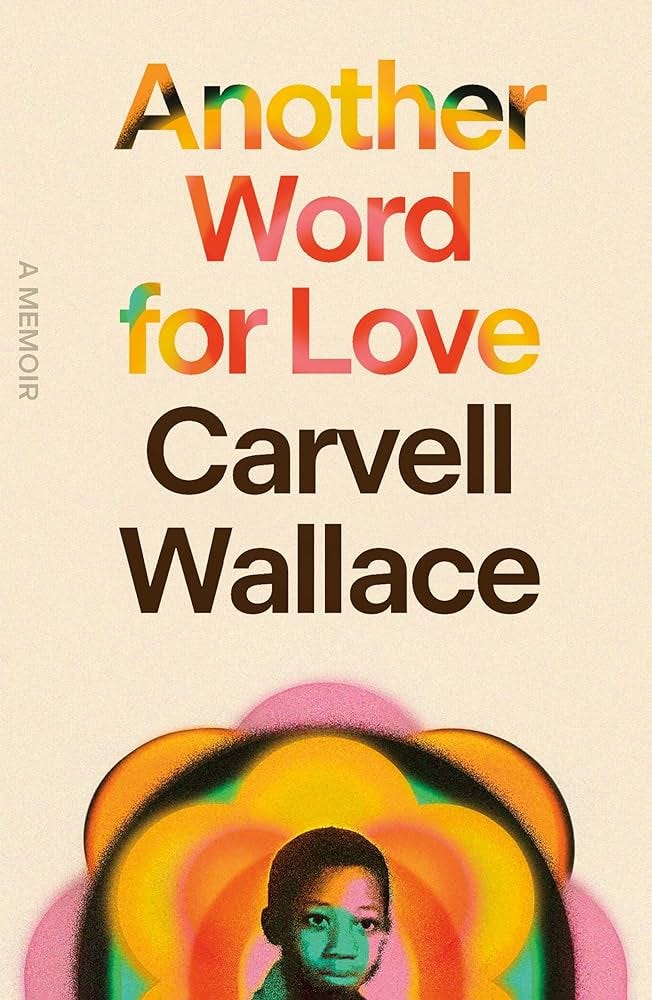

These are some of the transformative words, among so many others, in Carvell Wallace’s new memoir, Another Word for Love. In the tradition of memoirs that mine the personal for the political, the natural for the cosmic, the specific for the universal, Carvell has written a book that will definitely free people in all kinds of important ways. I love how he pays attention, how he practices love, how he insists on a different world now.

I met Carvell through our collaborative work co-hosting a Slate podcast (you can listen to me interviewing him here) and I’m always blown away by how emotionally insightful and humane he is with our guests and experts on the show. If you don’t already know his work, now is the time. Buy the book. Read or listen to it (I bet it is an amazing listen!). Listen to his episodes on the podcast. You will be nourished. Meet Carvell…

Courtney Martin: You give us so many “words for love” in this book--to change, to return, to be made whole, to truly consent. Did you set out with these different ways of writing about love in mind or did you discover them through the process of writing?

Carvell Wallace: The second thing for sure. The title of the book was given to me by a good friend and writing colleague, Nina Renata Aron. We were at a small backyard barbecue and I was describing what I was trying to write, and she just said the phrase. Like many good ideas, it immediately struck me and I couldn’t shake it. Even after that, I didn’t exactly have a plan to use the phrase as a kind of refrain in the text, but as I was writing, it started to become clear that certain paragraphs, sentences, images, and ideas were other ways of describing love, so it felt right to name that explicitly in the text. I think of love more as a practice and a way of living than a feeling, so I like the fact that the book ends up being a record of that practice.

There are so many powerful relationships woven into this book. How did you think about writing about people you love? Did you apply the principles of consent to the publishing process, or some other framework?

I ran some chapters by the people in them and others I did not. I sort of was guided by Mary Karr’s framework that if it happened to you it’s your story and you’re free to tell it. But if it happened to someone else, it’s their story and you should run it by them.

With that in mind, depending on my relationship with the people involved and what is in the book about them, I either: A) told them what I was writing about them and how, B) gave them the text to read and give feedback on, or C) didn’t tell them at all because I felt that doing so would unhelpfully interfere with my ability to tell my truth.

That said, I tried to be as generous as I could to everyone, for no other reason than the idea behind the original book pitch was that everyone – even a person who hurt me – has a story to tell. I tried to place my personal hurt at their hands within the context of the larger story about our relationship, which is by no means solely composed of hurt or pain.

There are also people who may have had a significant impact on me but whose stories I don't care to explore at this time, and they are not in this book.

One person asked me to take things out of the book and I did that. I connected with another person who I hadn’t talked to in years, gave them the chapter about them, and we had a tremendously powerful and healing conversation about our youth, ways we hurt each other, and where we are now. We both made amends for things we’d done, many of which the other person didn't remember. There is a kind of love that goes on forever with someone you loved when you were young. They become like family, you are infinitely tethered. I find that sweet.

What do you hope this book does for readers?

I may expect more than is possible, but I hope this book makes it easier and more possible for readers to disrupt systems of oppression and contribute meaningfully to the collapse of imperialism in all its manifest forms.

You write about nature so beautifully. When did you fall in love with nature or were you always?

I don’t think there was a specific moment, it just sort of snuck up on me. How can you not love nature when you are struggling under human violence and oppression? Nature is endlessly beautiful, and truly carries with it some kind of love. I don’t know how else to explain it. It’s not a personal, ego feeding love, but a love that has to do with clear sight, and the force of life. Nature will kill you too, but it won’t kill you specifically because you’re Black, Trans, Poor, etc, which is more than I can say for our human systems. Nature will treat you the exact same no matter your identity. This, in and of itself, is a form of liberation. Thus, nature is truly woke.

Anyway that’s a tangent, As mentioned in the book, I had a job in my twenties where we led backpacking trips for teens, and during that time I did some training with Bay Area Wilderness Training. That was definitely an introduction that allowed me to begin to experience nature on my own terms and to gain some sense of its liberatory power, which I would be pursuing to varying degrees for the rest of my life.

You write, “It is the end of everything, which is another way of saying it is the beginning of everything. It is the end of the day, which is to say it is the beginning of the stars and the beams of moonlight bathing the chuparosas and the ponderosa pines. It is the end of isolation, which is another way of saying it is the beginning of the embrace in which we mourn and wail, love and weep. It is the end of supremacy, which is another way of saying it is the beginning of communication with one another on the wind, our poems carried like pollen from one clump of us to another.” What is this book the end of in your own life? What is it the beginning of?

I’d say this book is the end of a certain kind of hiding and fear-driven self-protection. To paraphrase Audre Lorde, my silence didn’t protect me as much as I thought it did. Perhaps it is also the beginning of a new kind of ownership of the self, which by definition would make it the end of your ownership of me.

We have donated $250 to this GoFundMe in honor of Carvell’s labor and Carvell has matched. Listen here for more Carvell. Buy the book here.

I’m really resonating with this opening quote and looking forward to reading the book! Thanks for sharing it with us Carvell & Courtney.

Buying this immediately!!! Thank you.